- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- The Rematriation of Indigenous Place Names

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

This report is about the relationship between the petrochemical industry in Ontario’s Chemical Valley and Aamjiwnaang First Nation. Central to this relationship is pollution: the spills, flares, air releases and how those events are communicated to the community.

Communication about pollutants is regulated by provincial and federal governments, which actually provide limited oversight, allowing Shell, ExxonMobil, and other petrochemical polluters to form their own industry associations that determine what information is provided to the community and when.

A notification system to alert those in the Valley to any spills, releases, or accidents has been designed by the industry associations to obscure the environmental violence they are responsible for. Since 2004, community members affected by this violence — those from Aamjiwnaang First Nation — have collected data on the notifications that reveals how companies purposefully try to hide their harmful activities and bad faith practices.

Aamjiwnaang First Nation is most directly affected by the infrastructure of colonial entitlement that allows government and industry to pollute in Chemical Valley, but data misinformation is a global project headed by some of the biggest multinational oil companies in the world. While better data will not end pollution, fossil fuel capitalism, or colonialism, environmental evidence and community expertise can be used to imagine better ways to collect, manage, and govern pollution data.

This Special Report describes the permission-to-pollute system in Chemical Valley, explains how industry manipulates data, and looks to community members of Aamjiwnaang First Nation for alternatives to data colonialism.

This report is a collaboration between Yellowhead Institute and the Technoscience Research Unit at the University of Toronto.How can Indigenous environmental data justice practices help protect communities from the bad faith misinformation practices of the petrochemical industry?

KEY QUESTIONS

- How can Indigenous environmental data justice practices help protect communities from the bad faith misinformation practices of the petrochemical industry?

- Why do the provincial and federal governments allow multinational corporations to decide how to share pollution information with First Nations?

When you stand anywhere in Chemical Valley, the intensity of pollution and industrial activities is immediately evident. You can see the plumes of smoke in the sky, the bright flares on top of the stacks, the pipelines crisscrossing the land, the railways cutting across the roads, and the hundreds of rusty unlabeled tanks. Sometimes, you can smell something in the air, feel a sensation on the skin, experience disrupted breathing, or have a mysterious headache interrupt your day...

- Vanessa Gray, Beze Gray, Fernanda Yanchapaxi, Dr. Kristen Bos, Dr. M. Murphy

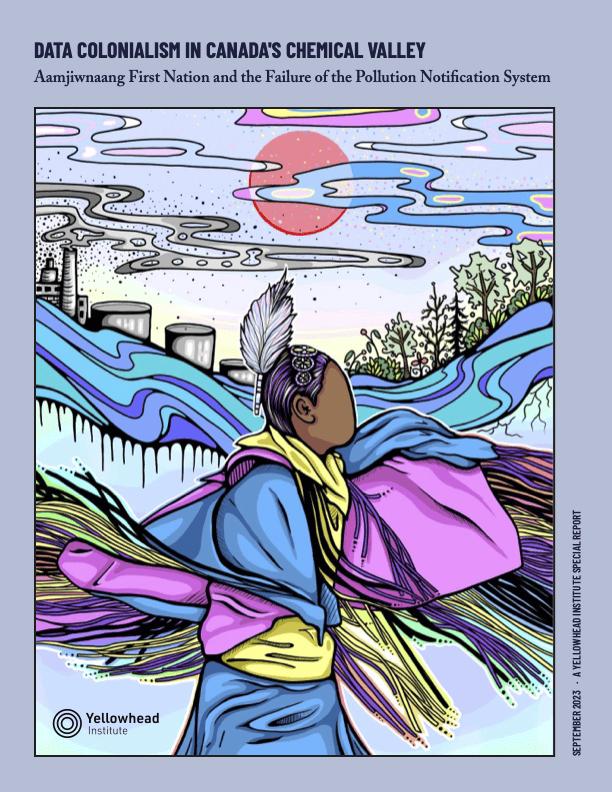

artist

Mo Thunder

Haudenosaunee (Oneida Nation of the Thames), French-Canadian, Anishinaabe (Aamjiwnaang First Nation)