- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- The Rematriation of Indigenous Place Names

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

STARTING IN 2023, Canada began the process of restitution to First Nations in Northern Ontario and the Prairies for their failure to honour the “Cows and Plows” elements of the Numbered Treaties. Restitution in these cases has involved significant specific claims settlements, resulting in debate among communities about whether to accept their terms. While some have done so, others are still considering their options.

So, what does “Cows and Plows” mean for communities? What are the legal implications of settlement? And is this really the treaty relationship that Indigenous peoples expect with Canada?

What is “Cows and Plows”?

”Cows and Plows” is a term that refers to the process of settling unfulfilled promises related to agriculture and livelihood under Treaties 1 to 11, known collectively as The Numbered Treaties. Made between 1871 and 1921, these post-confederation agreements between Indigenous peoples and Crown representatives allowed newcomers to share and settle on lands that would become part of Canada.

Within the text of each of the Numbered Treaties, various provisions are made to assist First Nations in learning about new livelihoods by providing farm animals and implements while also providing protections to ensure the continuity of our existing ways of life.

Those provisions often include agricultural equipment, animals, and seed. The Canadian federal government refers to these components of the Numbered Treaties as Agricultural Benefits. In many cases, those promises have gone unfulfilled or have been only partially fulfilled, and many First Nations are negotiating settlements for compensation. Allegations about the Crown’s failure to fulfill these promises are known as Agricultural Specific Claims, and are also informally called “Cows and Plows.”

Before 2023, ”Cows and Plows” claims were adjudicated under the general specific claims process. But, in early 2023, the federal government introduced an Expedited Resolution Strategy to move these claims forward (Government of Canada 2025a).

Cows, Plows, and Specific Claims

In Canada, Specific Claims are a category of land claim that deals with breaches of treaty obligations and generally relate to the mismanagement of reserve lands and other First Nation assets. For example, a specific claim could relate to a shortfall in reserve land allocation, mismanagement of Indigenous assets, or breaches of the Crown’s responsibilities under the Indian Act (Government of Canada 2025c).

Once a specific claim is filed, it is considered “under assessment.” This stage includes “research and analysis” carried out by the Government of Canada, followed by the Justice Department preparing a legal opinion on the specific claim. At the next stage of the process, depending on the Justice Department’s opinion, the First Nation that filed that claim is “invited to negotiate” with the federal government. Once an agreement is reached, the specific claim is considered “settled through negotiations.”

While many specific claims in Canada are rejected, some claims are successfully negotiated. Others are pursued through litigation, and the specific claims process itself is changing. Based on extensive engagement conducted with First Nations in 2019-2021, the Assembly of First Nations forwarded their Specific Claims Reform Proposal. The proposal calls for establishing an independent specific claims process, which is now undergoing development between the Assembly of First Nations and the Government of Canada (Assembly of First Nations, 2025). According to the Government of Canada, the intent of the resolution process is to address the Crown’s failure to provide agricultural benefits in relation to the Numbered Treaties.

All treaties include some form of reference to agricultural benefits and/or assistance. While the written text outlining specific agricultural items varies slightly from Treaty to Treaty, they express similar terms. First Nations had expectations when they agreed to share the land with settlers. For example, Treaty 7 states:

“Her Majesty agrees that the said Indians shall be supplied as soon as convenient, after any Band shall make due application therefor, with the following cattle for raising stock, that is to say: for every family of five persons, and under, two cows; for every family of more than five persons, and less than ten persons, three cows, for every family of over ten persons, four cows; and every Head and Minor Chief, and every Stony Chief, for the use of their Bands, one bull; but if any Band desire to cultivate the soil as well as raise stock, each family of such Band shall receive one cow less than the above mentioned number, and in lieu thereof, when settled on their Reserves and prepared to break up the soil, two hoes, one spade, one scythe, and two hay forks, and for every three families, one plough and one harrow, and for each Band, enough potatoes, barley, oats, and wheat (if such seeds be suited for the locality of their Reserves) to plant the land actually broken up. All the aforesaid articles to be given, once for all, for the encouragement of the practice of agriculture among the Indians” (Government of Canada 2013).

Indigenous Interpretations of the Numbered Treaties

It is important to note that we are in this process because Canada has, in fact, violated its commitments regarding livelihood and agriculture under the Numbered Treaties on an ongoing basis. By way of resolution, Canada has consistently taken the position that its failure to fulfill commitments can be addressed through a one-time settlement. This position is based on a one-sided view of treaties as transactions involving the exchange of land for material goods. But this approach privileges the written text of treaties recorded by the Crown and obscures Indigenous knowledge of treaties as agreements to share, rather than cede, the land.

Indigenous visions of treaties understood the Crown’s agricultural obligations as intended to support Indigenous peoples in learning about new livelihoods. But this commitment was not frozen in time nor was it limited to the exchange of a scant number of material items; rather, the relationship and associated supports for treaty partners were intended to grow and be regularly renewed through ongoing dialogue and negotiation.

This is consistent with a relational approach to treaties that flows from their spirit and intent, and understands them to be mutually beneficial and lasting relationships that would endure as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the rivers flow.

Oral histories and Indigenous knowledge of treaties do not conceptualize the Crown’s treaty commitments in the area of agriculture as one-time exchanges of animals and agricultural items. Instead, these commitments are symbols of a lasting, reciprocal, and mutually beneficial relationship intended to help mitigate the impacts that settler colonialism, and specifically the presence of permanent settler populations, would have upon Indigenous peoples and lands. Importantly, the intent was for the relationship to be revisited and re-assessed as economic times and environments changed (Cardinal & Hildebrandt, 2000).

For Indigenous Peoples, agricultural commitments are related to the Queen’s offer of protection and benevolence, as well as promises related to future livelihood and the preservation of a way of life. Crown treaty commissioners assured Indigenous Peoples that the Crown would ensure our welfare better than the Hudson’s Bay Company, that our existing way of life would not be disturbed, and that we would be provided with the means to adopt agriculture if we wished (Office of the Treaty Commissioner 1998, 24).

According to Indigenous knowledge holders, the true nature, spirit, and intent of treaties were meant to ensure that both First Nations and settlers benefited equally from the agreement to share the land. Elders have also observed that the written texts of treaties often distorted or misrepresented First Nations’ expressions of treaty relationships, omitting many oral promises and, in some cases, including written terms that were never discussed during treaty negotiations (Carter, First Rider & Hildebrandt, 1996).

“When Elders describe the wealth of the land in terms of its capacity to provide a livelihood, they are referring not simply to its material capabilities but also to the spiritual powers that are inherent in it. This includes all the elements of Creation that the Creator gave to the First Peoples: Mother Earth, the sun, air, water, fire, trees, plant life, rocks, and all the animals” (Cardinal & Hildebrandt 2000, 43).

After signing the treaties, Indigenous understandings were overwritten by various laws and policies that limited or controlled the transition to agriculture for those interested. These included, but were not limited to, those imposed through the Indian Act 1876, and its numerous amendments, as well as the reserve and pass systems. Many First Nations had little choice in where reserves were located, and reserve land was often unsuitable for farming. Indigenous people also could not farm or get credit or capital outside the reserve. Additionally, our ability to sell produce and to buy and stock goods was heavily regulated by external parties (Carter 1989).

Settlement Certainty, Finality & Indemnification

Today, many of our communities are considering whether to negotiate and accept Agricultural Benefits, or “Cows and Plows” settlements. Not only is the history of Indigenous-settler treaty relations contentious, so too is the specific claims process. This is driving much of the debate among communities that are questioning the settlement. There are several important considerations and complexities relating to the Agricultural Benefits claim process.

First, the Agricultural Benefits Specific Claims process treats violations of the Treaty as isolated, one-time events. It fails to consider the ongoing, cumulative, and future impacts of Crown neglect related to agriculture, livelihoods, and the broader treaty relationship. The process only includes past breaches of agricultural items and benefits listed in the text of treaties recorded by the Crown (claims that are over 15 years old). First Nations cannot file a specific claim related to current or future treaty obligations under the Specific Claims Policy and the Specific Claim Tribunal Act. And, once signed, the “Cows and Plows” settlements limit the ability of First Nations to pursue future forms of redress or compensation for the Crown’s failure to enact its treaty obligations to agriculture through release and indemnification clauses.

The Canadian federal government clearly states that when accepting expedited agricultural settlements, First Nations must “provide the federal government with a release and an indemnity with respect to the claim, and may be required to provide a surrender, end litigation or take other steps so that the claim cannot be re-opened at some time in the future” (Government of Canada 2021).

Because First Nations must agree to release and discharge Canada from any ongoing liability or future proceeding regarding agricultural benefits promised under the treaty, the settlements extinguish our ability to advance future claims relating to the Crown’s related treaty commitments. This finality conflicts with Indigenous understandings of treaty relationships and the agricultural and livelihood provisions that were intended to be living and subject to regular renewal.

Release clauses mean that once the claim is concluded, Canada is released from any future claims or liabilities related to the provision of agricultural implements and assistance.

First Nations are still free to pursue modern or historical claims against the Crown concerning any other legal issue, but not in the areas covered by the claim. Compensation is a one-time payment that can never be revisited, even to account for inflation or changes in legal and political standards and processes over time.

As Canada notes, “If the Tribunal decides that a specific claim is invalid or awards compensation for a specific claim,

(a) each respondent is released from any cause of action, claim or liability to the claimant and any of its members of any kind, direct or indirect, arising out of the same or substantially the same facts on which the claim is based; and

(b) the claimant shall indemnify each respondent against any amount that the respondent becomes liable to pay as a result of a claim, action or other proceeding for damages brought by the claimant or any of its members against any other person arising out of the same or substantially the same facts.”

Related to the Release Clause is the Indemnity Clause. Indemnity means that if Canada is sued again for a similar claim in the future, it will not be responsible for the risks and costs of that lawsuit. In the event of such a case, the First Nation would be responsible for defending and paying Canada’s legal fees and expenses.

Second, restitution via compensation is a narrow and limited form of reparation that provides economic incentives to First Nations, effectively absolving the Crown of its liabilities. It is important to interrogate whether this form of settlement represents a substantive form of justice and accountability, or whether it reproduces a transactional approach to treaties and only offers a partial remedy for the Crown’s violations of its obligations relating to livelihood and assistance. From a relational view of treaties, the “Cows and Plows” settlement process can be seen as a containment strategy relative to broader possible forms of political and legal transformation, aligning with the Canadian federal government’s ongoing efforts to offload its liabilities under the Numbered Treaties and reduce treaty implementation to Indigenous participation in Canadian economic development schemes.

A third consideration is the nature of the compensation offered. Under the agricultural benefits expedited resolution strategy, compensation is based on literal interpretations of the treaty terms recorded by the Crown. Agreeing to submit a claim under the Specific Claims process almost always requires First Nations to suppress their own interpretations and rely on the written, transactional text. Additionally, the process only considers a limited amount of financial harm; it does not account for inflation in the value of recorded agricultural items or for the non-financial harms caused by the Crown’s failure to support Indigenous transitions to a new way of life.

Finally, it offers no remedy for the wider harms that First Nations have suffered and continue to endure as a result of the Crown’s ongoing violation of the treaty relationship generally, as well as in other specific areas. Failure to enact part of a treaty impacts the entire treaty relationship. Livelihood and way of life obligations do not exist in a vacuum; they are interconnected with other aspects of the treaty and cannot be reduced to the exchange of agricultural tools. Livelihood must be understood in relation to many other dimensions of treaties, such as Indigenous peoples’ commitment to share (not cede) the land while holding some back for the exclusive use of Indians, as well as Crown commitments to protect and not interfere with Indigenous peoples’ existing ways of life, limit the harmful effects of increased settler presence, and only bring changes that would improve (and not diminish) the lives of future generations of Indigenous peoples.

Compensation does not deal with related matters of land and resource theft, or Indigenous legal and political subordination, which have historically restricted and continue to impact our ability to learn about and share in new livelihoods, in addition to practicing existing ones.

All of this being said, it is important to recognize that First Nations entitled to agricultural settlements hold diverse opinions, and the decision to accept or reject a settlement is part of each community’s self-determination. For Nations that have accepted settlements, some explain that they see it as one step closer to Canada fulfilling its treaty promises (English River First Nation, Government of Canada 2024b), as a way to secure a better future for Nations and their members (Chief Tammy Cook-Searson, Lac La Ronge Indian Band), or as enabling Nations and their members to decide what will work best in today’s economic realities (Chief Derek Nepinak, Minegoziibe Anishinabe, Pine Creek First Nation). Regardless, no settlement should absolve the Crown of its treaty obligations in any area forever, as this would violate the ongoing, living nature of the treaty relationship as understood by Indigenous peoples.

The Numbered Treaties: Living Agreements or Transactions?

The most immediate limitation of the Agricultural Benefits claims process is that it favors and relies on the Crown’s narrow written record of treaties. In contrast, Indigenous knowledges and histories of treaties include a broader range of oral obligations and commitments related to the nature of the intended relationship, which were not included in the text.

Settlements for agricultural benefits claims can reinforce an understanding of treaties as one-time transactions of material items rather than living agreements to be revisited and renewed. This gives the Crown’s account of treaties greater authority than Indigenous ones. The intent of the process is for the Crown to gain “certainty” — settlements expunge current and future liabilities and ensure the finality of these claims.

This sense of finality is a challenge. Social and legal standards and precedents are constantly evolving, and the current resolution process restricts the opportunity for First Nations to advance claims related to agriculture and livelihood in more substantive ways in the future. Say, for instance, that a First Nation wanted to advance a future claim concerning agriculture based on oral histories and the spirit and intent of the treaty rather than the written text of items recorded. In this case, the Crown may be indemnified against such an action. Or, consider that a First Nation were to advance a broader claim relating to way of life in the future, the Crown could be indemnified against all or part of that claim since it could argue that its obligations and responsibilities relating to “way of life” end with the provision of agricultural benefits.

Ultimately, discussions about “Cows and Plows” agricultural settlements reflect different interpretations of treaties. While Indigenous peoples view treaty relationships as ongoing land-sharing agreements meant to benefit both First Nations and settlers as social and economic conditions continue to evolve and shift, Canada’s settlement process represents one-time compensation that aims to absolve it of its failure to uphold treaty promises and minimize its future liabilities.

These are the risks that we take by accepting the “Cows and Plows” settlement. As we have mentioned above, some will accept those risks in order to receive long-overdue and owed restitution for generations of injustice. Others may not. Ultimately, it is up to First Nations to decide what is best for their families and communities. Our hope is that this resource provides insights, considerations, and questions to help communities make informed decisions.

Acknowledgment

We want to acknowledge the critical on-the-ground advocacy and educational work that Indigenous women such as Deanne Kasokeo and Rachel Snow have done to share knowledge about how Agricultural Benefits Agreements impact treaties at a community level.

Appendix A: Settlement Amounts (by calendar year)

| Settlement Year | No. of First Nations | No. of Claims | Total amount of Settlements |

| 2017 | 8 | 8 | $198,235,954.00 |

| 2018 | 11 | 11 | $827,425,361.00 |

| 2019 | 1 | 1 | $239,422,052.00 |

| 2021 | 5 | 5 | $601,438,555.00 |

| 2023 | 6 | 6 | $401,406,628.00 |

| 2024 | 18 | 18 | $2,844,772,003.00 |

| 2025 | 22 | 23 | $3,041,703,390.00 |

| Total | 71 | 72 | $8,154,403,943.00 |

Number of Settlements by Treaty Area

| Treaty No. | No. of Agreements | No. of Bands

in Treaty Area |

Percent of FNs with

Completed Agreements |

| 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| 4 | 13 | 33 | 39 |

| 5 | 1 | 40 | 2.5 |

| 6 | 31 | 47 | 66 |

| 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 8 | 27 | 40 | 67.5 |

| 9 | 0 | 36 | 0 |

| 10 | 4 | 7 | 57 |

| 11 | 21 | 0 | |

| Totals | 71 | 275 | 26 |

Endnotes

Ahluwalia, Harjaap. “Canada First Nation secures $601.5M settlement for Treaty 6 agricultural promises.” JURISTnews, August 27, 2024. https://www.jurist.org/news/2024/08/canada-first-nation-secures-601-5m-settlement-for-treaty-6-agricultural-promises/

Assembly of First Nations. “Holding the Federal Government accountable for the failure to uphold and fulfill First Nations treaty rights.” Land Rights & Jurisdiction, 2025. https://afn.ca/environment/land-rights-jurisdiction/specific-claims-policy-reform/

Baxter, Dave. “Manitoba First Nations community clears final hurdle in $200M “cows and plows” settlement with feds to right century-old wrong.” In The Canadian Press. Canadian Press Enterprises Inc. March 4, 2024.

Cardinal, Harold, and Walter Hildebrandt. Treaty elders of Saskatchewan : our dream is that our peoples will one day be clearly recognized as nations. University of Calgary Press, 2000.

Carter, Sarah. “Two Acres and a Cow: ‘Peasant’ Farming for the Indians of the Northwest, 1889–97.” The Canadian Historical Review 70, no. 1 (1989): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.3138/CHR-070-01-02.

Carter, Sarah, Dorothy First Rider, and Walter Hildebrandt. The True Spirit and Original Intent of Treaty 7. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996.

Government of Canada. 2024a. “Canada settles Agricultural Benefits specific claims with nine First Nations under Treaties 5, 6, and 10.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, October 18, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2024/10/canada-settles-agricultural-benefits-specific-claims-with-nine-first-nations-under-treaties-5-6-and-10.html

Government of Canada. 2024b. “English River First Nation and the Government of Canada sign agreement on Canada’s failure to uphold the cows and ploughs promise in Treaty 10.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, March 14, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2024/03/english-river-first-nation-and-the-government-of-canada-sign-agreement-on-canadas-failure-to-uphold-the-cows-and-ploughs-promise-in-treaty-10.html

Government of Canada. 2025a. “Canada Settles Agricultural Benefits Specific Claims with Fourteen First Nations under Treaties 4 and 6.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, February 21, 2025. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2025/02/canada-settles-agricultural-benefits-specific-claims-with-fourteen-first-nations-under-treaties-4-and-6.html.

Government of Canada. 2025b. “Specific Claims Tribunal Act (S.C. 2008, c. 22).” Legislative Services Branch, July 31, 2025. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/S-15.36/FullText.html.

Government of Canada. 2025c. “Specific Claims.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, February 5, 2025. https://rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100030291/1539617582343.

Government of Canada. 2021. “The Specific Claims Policy and Process Guide.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, June 4, 2021. https://rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100030501/1581288705629.

Government of Canada. 2013. “Treaty Texts: Treaty and Supplementary Treaty No. 7.” Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, August 30, 2013. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028793/1581292336658.

Office of the Treaty Commissioner. Statement of Treaty Issues : Treaties as a Bridge to the Future. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, and Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1998.

Starblanket, Gina and Courtney Vance. “The ‘Cows and Plows’ Treaty Settlement: Overview and Implications,” Yellowhead Institute. 07 October 2025. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2025/the-cows-and-plows-treaty-settlement-overview-and-implications/

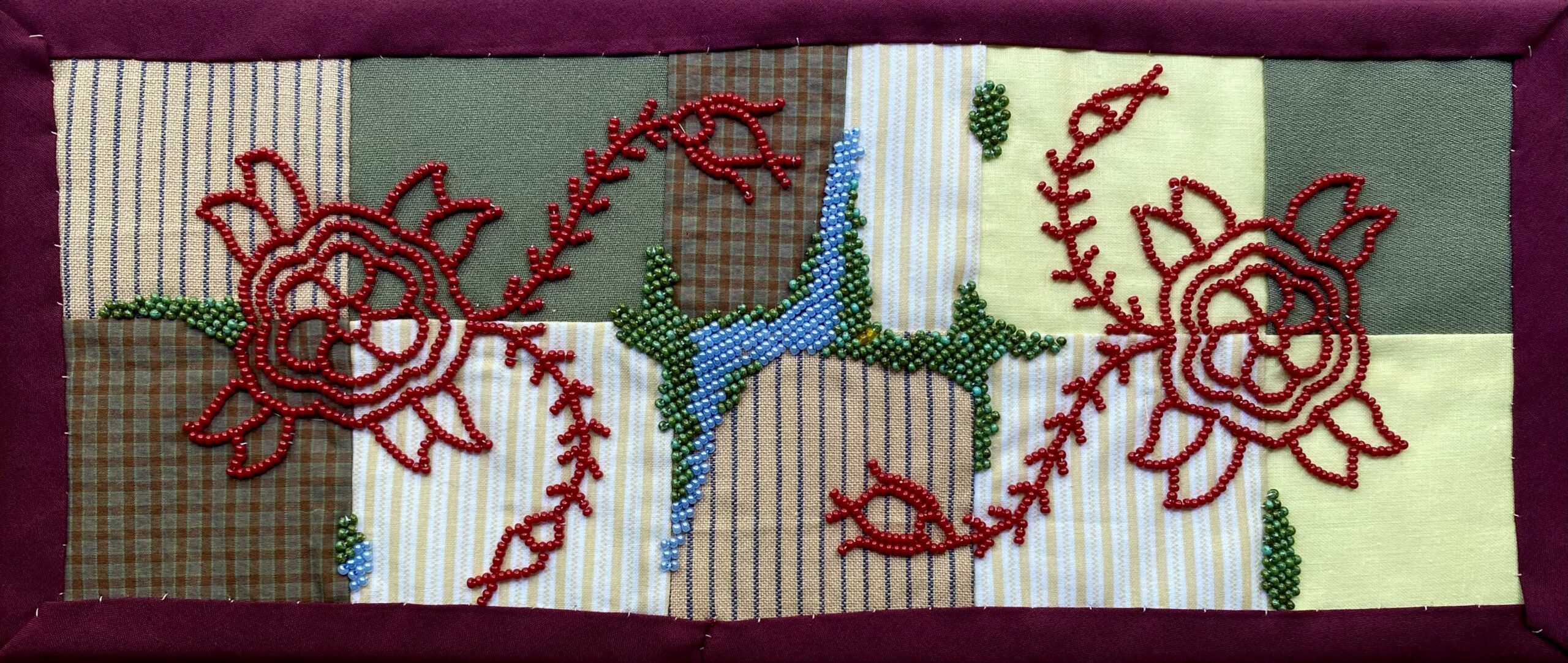

Artwork: Cash Crop (2025), Bailey Bornyk

The hand stitched quilt portrays an aerial view of the prairies that, over time, have been surveyed and divided into private sections of monoculture. An overlay of red beadwork echoes traditional design language among Michif people on the plains. The piece explores themes of land displacement, agriculture, and the persistence of Indigenous connection to ancestral land.