- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

Cities have been and will always be Indigenous land. Yet, these lands have witnessed continuous assaults on Indigenous sovereignty. Demarcations of belonging and un-belonging legislated by governments and enforced by police have facilitated Indigenous dispossession and displacement to make room for settler colonialism — its institutions and ideals — to thrive. Central to this strategy has been the labelling of Indigenous people as immoral, advancing normalizations of Indigenous disposability in this country with fatal impacts.

This legacy is reflected today in a complexity of needs experienced by many urban Indigenous people, which includes a need for adequate medical support provided through harm reduction initiatives. Unfortunately, for Indigenous people in the city who use drugs, the violent tradition of displacement and removal, fuelled by stigmatization, continues with the enactment of Bill 6.

What is Bill 6?

Passed in June 2025, Bill 6 aims to “restrict the public consumption of illegal substances” by increasing criminal punishment. Those suspected of using drugs may receive a fine of up to $10,000, be sentenced to six months in prison, or both. The Bill does contain exceptions, namely, if the substances are consumed within a safe consumption site. But since the province has shuttered most safe consumption sites following the passage of Bill 223 in late 2024, that exception is meaningless. Devastatingly, we have seen a surge in overdoses at drop-in centres throughout Toronto since the removal of essential medical care offered through safe consumption sites. Now, people who use drugs face further threats. Simply put, Bill 6 targets and criminalizes people who use drugs who have nowhere to go but outside.

Without a doubt, Indigenous people who use drugs will bear the brunt of the violence of Bill 6. Indigenous peoples are not only overrepresented as drug users and victims of toxic drug supply but also experience significantly greater incidents of police violence.

These issues are compounded by the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples experiencing houselessness, with public drug use being an inevitability when vast numbers of our people are without homes.

Dangers of Displacement in a Toxic Drug Crisis

We are facing a deadly, toxic drug crisis: a public health emergency characterized by a drug supply contaminated with highly potent, unknown, and toxic substances. The criminalization of drug use exacerbates this crisis as contaminated supply proliferates on the black market leading to increased contact with tainted drugs and unsafe methods of use.This ultimately presents greater risk of overdose, risks for infection, as well as other long-term, debilitating health impacts that can forever impact the lives of those who survive.

While federal and provincial governments double down on ineffective carceral approaches, studies repeatedly prove that the most effective practice to mitigate the dangers of the toxic drug supply is through harm reduction measures — measures that were directly targeted and removed with the passage of Bill 223.

In the fatal absence of effective, research-backed government initiatives, people who use drugs create their own mutual aid solutions, such as encampments, to keep each other safe. But the passage of Bill 6 threatens these community-based, life-saving initiatives, and further endangers those navigating the interlocking realities of Canada’s toxic drug supply and houselessness.

High rates of Indigenous outdoor houselessness is a direct result of generations of Indigenous displacement enabled through the process of settler colonialism. In Toronto, Indigenous people make up 3 percent of the overall population, but represent 31 percent of people experiencing houselessness outdoors.

Since the start of “Canada”, Indigenous Peoples have been forced out of their territories and onto reserves, pushed out of reserves into cities, and in cities, experience endless displacement from space to space.

It is clear there is no place suitable for Indigenous people to exist within the confines of the settler colonial imagination. Whether a person is compelled to leave their community due to unique needs or dismal conditions, or they are forcibly removed from a park bench in Toronto, these are all experiences of displacement that are an assault on Indigenous sovereignty and autonomy.

The infringement on Indigenous autonomy in the name of public health or safety cannot reasonably be justified in light of the evidence: the consequences are fatal.

When people on the streets who have found safety with each other are dispersed and displaced, they are pushed into isolation and removed from safety networks and trusted sources, increasing exposure to unknown drugs. Drug users themselves are often first responders in their own community. When forced to use alone, they are more at risk of overdose.

This phenomenon doesn’t end with housing — someone offered indoor space in an unknown neighbourhood, far from their health supports and community, is also at increased risk of overdose in isolation. Evidence demonstrates that the majority of overdoses take place when people use alone and indoors. Now, individuals who use drugs face two options: lose community safety support and be exposed to greater risks of overdose, or be threatened with harsher criminalization if they choose or are forced to stay outside.

Police only need to suspect an individual of using drugs to charge them under Bill 6, empowering them to surveil, displace, and criminalize accordingly. This creates heightened threats toward any Indigenous person on the streets, whether they use drugs or not, to be discriminated against and charged simply for not having anywhere else to go.

With Bill 223 and Bill 6 now law — despite abundant evidence of the measures and services needed to keep Indigenous people safe and alive amid the toxic drug crisis — life-saving services are cut, and criminalization is magnified.

The Increasing Prevalence of Police Violence

Increased displacement and criminalization will not stop people from using drugs. It can’t mitigate the dangers of the toxic drug supply. And it won’t make Indigenous people who find themselves on the streets disappear. It will justify police violence against Indigenous people in the city.

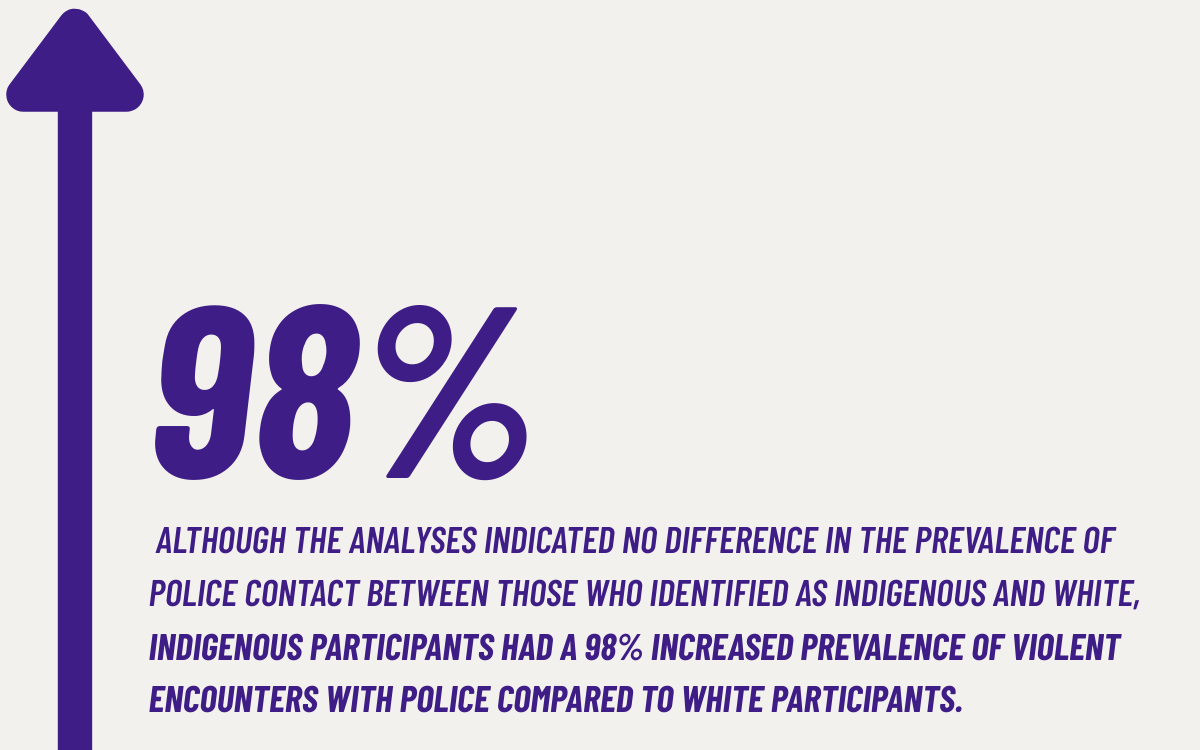

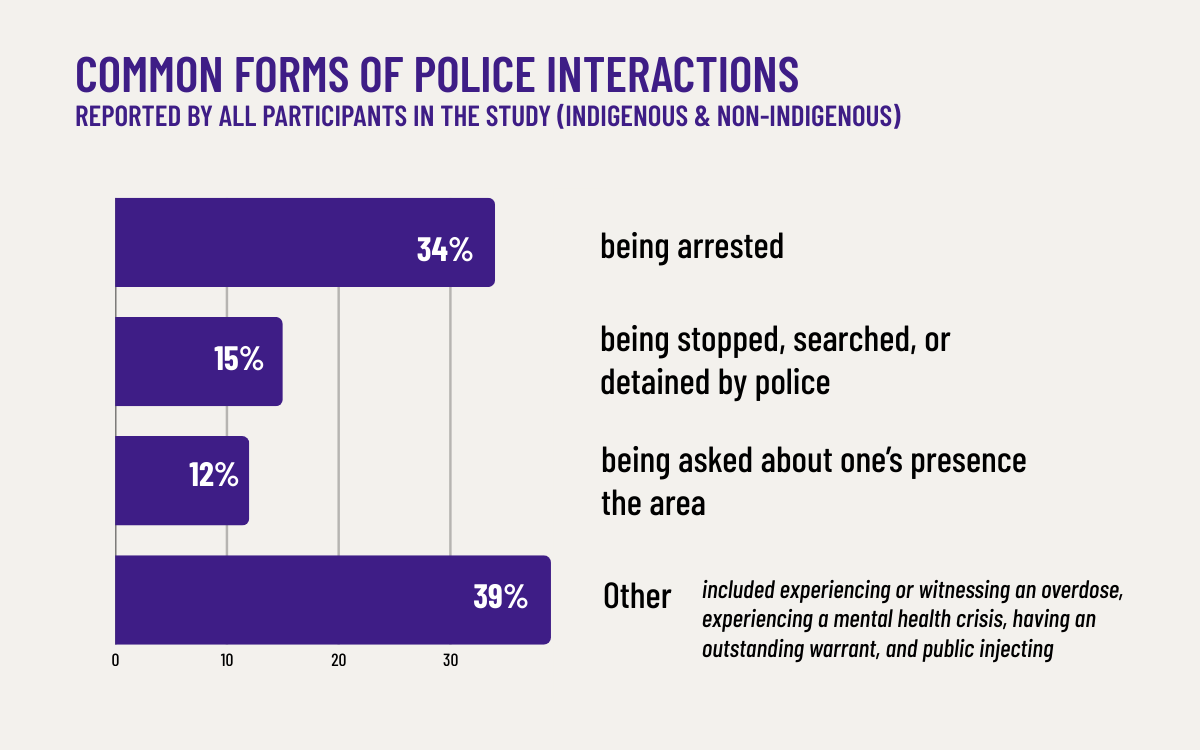

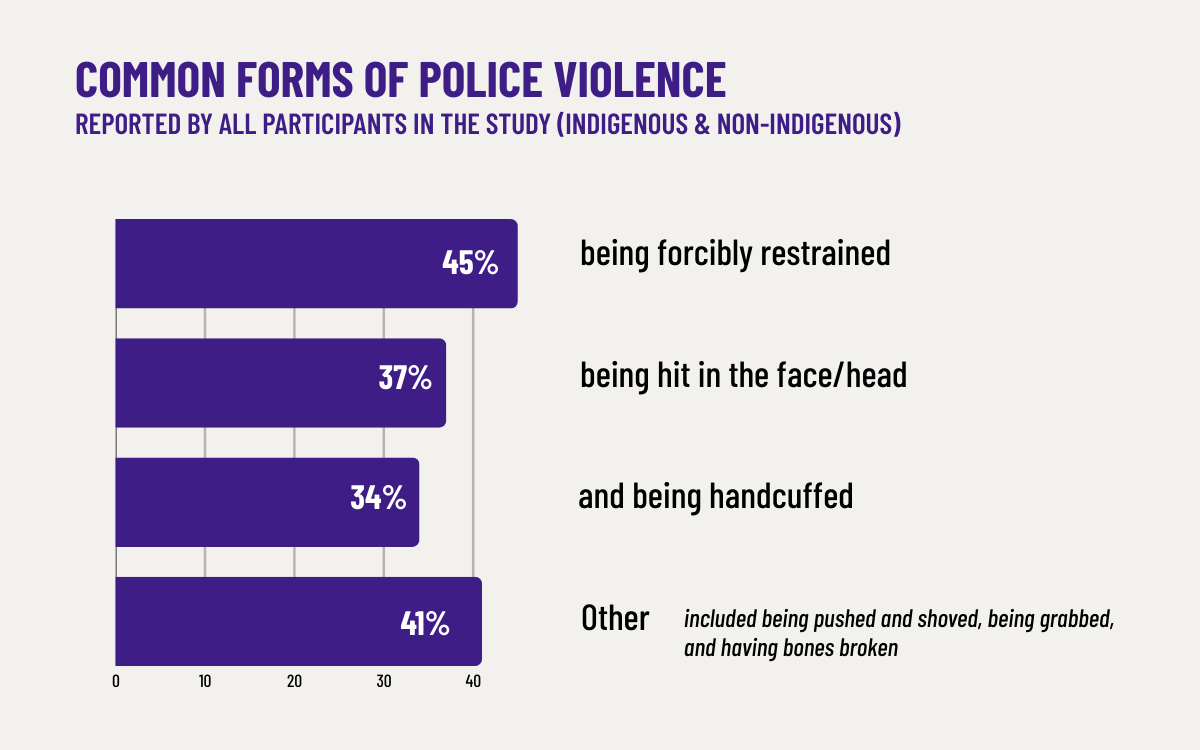

Research1 conducted by the Centre for Drug Policy and Evaluation and made available to Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction examined experiences of police contact and violence towards people who inject drugs in Toronto. The research found that there was no difference in the prevalence of police contact between those who identified as Indigenous and those who identified as white; however, Indigenous participants had 98% increased prevalence of violent encounters with police compared to white participants.

This research aligns with the Toronto police’s own race-based data, which demonstrates discrimination against Indigenous people who encounter police: Indigenous people consistently experience higher-than-average detainment after arrest compared to the rest of the population, and Indigenous women are almost twice as likely (1.9x) to be arrested than non-Indigenous women. In the context of this reality, Bill 6 effectively exposes our Indigenous relatives to greater violence from the known threat of discriminatory police practices on top of the removal of community support to safely use drugs in the absence of safe sites.

Bill 6 and the Ongoing Assault on Indigenous Sovereignty

Bill 6 effectively dismantles pre-existing due process around encampment removal, including the city’s previous notification process, which prepared folks for the violence of displacement. Now, the police are empowered to search, seize, and displace, which advances serious threats to Indigenous people — those who are already facing the highest risk of overdose, homelessness, and police violence. Subsequently, Bill 6 raises concerns about the constitutional rights of Indigenous people to be on their own homelands as well as the responsibilities of the government to provide healthcare and housing to survivors and intergenerational survivors of colonial harm. Bill 6 facilitates the continued subjugation of Indigenous people through ongoing displacement from their lands and traditional territories and imprisonment.

These policies cannot be interpreted outside the context of settler colonialism. Indigenous people who find themselves on the streets and using drugs are survivors of intergenerational and continued colonial violence. While we confront a political project layered with myths of Indigenous disposability, we know these individuals are anything but.

Indeed, many of these same people on the streets are language speakers, ceremonial knowledge holders, and Elders who are consistently refused dignity and support. As Veronica Fuentes stated in a recent Yellowhead brief, “Indigenous Peoples have a lot to teach the world about living a good life and living the life we all deserve. These teachers can also be people who use drugs.”

Reconciliation and Land Back in the City

It is September, and we are approaching National Day for Truth and Reconciliation — a day when the country is meant to reflect on the harms inflicted on Indigenous people throughout our history and work to repair those harms as they ripple out throughout our settler colonial present.

If provincial and municipal governments cared at all about Truth and Reconciliation, they would support Indigenous autonomy and sovereignty — not continue to evict, arrest, and assault the most vulnerable members of our community.

This National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, you will hear land acknowledgements reciting territorial caretakers and stewards. Those stewards include the very people who are outside, keeping each other safe amid excessive attacks on their lives. This year, when you hear an Elder opening an Orange Shirt Day event with a prayer, you should know that there is an equally valuable knowledge holder not too far away being criminalized for where they lay their head to sleep.

While some can interpret Bill 6 as simply addressing public drug use, in the larger story of this country, it reinforces the legacy of Indigenous displacement, forced engagement with carceral systems, and removal from land. This legacy is one our governments say they wish to atone for on convenient days like National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. But repair is not possible without all Indigenous people. This includes Indigenous people who use drugs, and Indigenous people who are houseless.

Being empowered to exercise sovereignty over our bodies, over our health and well-being, as well as over our lands and waters on the other hand would be a reflection of reconciliation.This land has always been Indigenous land. This month, when people ask, “What does reconciliation really, tangibly look like?” or, “What does Land Back in the city mean?” This is where it should begin.

This Brief is a publication in the Yellowhead Special feature, Taking Care of Our Own: Perspectives on Indigenous-Led Harm Reduction. Produced by Community Engagement Specialist, Kelsi Balaban, and Yellowhead Fellow Sage Broomfield, this feature amplifies perspectives on Indigenous harm reduction as a vital tool in taking care of our own, inextricable from the broader movement toward Indigenous sovereignty.

Endnotes

1. Mitra S., Na Y., Eeuwes J., Smoke A., Owusu-Bempah A., Werb D. Police Encounters among People Who Inject Drugs in Toronto. Presented at the 12th Annual Conference for the International Network on Health and Hepatitis in Substance Users. Oct 8-11, 2024; Athens, Greece. Data is representative of a sample of 418 participants.

Olson Pitawanakwat, Brianna, Mskwaasin Agnew and Kelsi-Leigh Balaban. “Ontario’s “Safer Municipalities Act” (Bill 6) and the Criminalization of Indigenous People in the City.” Yellowhead Institute. 25 September 2025. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2025/ontarios-safer-municipalities-act-bill-6-and-the-criminalization-of-indigenous-people-in-the-city

Artwork: untitled, @gurl23