- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

I BEGAN WRITING this piece thinking about the interplay between policing and incarceration.

More specifically, about the vast amount of discretion police officers are permitted, and how the trajectory to incarceration is highly contingent upon folks’ “first point of contact” in the criminal justice system.

Given the tapestry of colonial systems of control, and our current socio-political climate regarding anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, my thinking kept cycling back to how the making of Canada as a white settler country relied upon the destabilizing of Indigenous socio-political systems in tandem with the implementation of the legally sanctioned practice of Black slavery through social control, displacement and incarceration.

From the passing of the 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act, which allowed the Canadian state to designate who was and wasn’t an “Indian” while attacking Indigenous women specifically, to 200 years of Black slavery erased from the collective consciousness of a Canadian nation (Nelson quoted in Brown, 2019), the creation of residential schools, and building of “lunatic asylums,” settler control of Indigenous and Black peoples has been undertaken through the formulation and administration of incarceration (Oikawa, 2012). This “national violence,” as Oikawa reminds us, was perpetuated to further nation building and remove from our national consciousness the visceral realities of conquest, replacing the narrative with nationalistic tropes of patriotic whiteness.

This practice of genocide – as it is seldom referred to in Canada due to the rhetoric of multiculturalism – involved the systematic targeting and over-policing of Black and Indigenous communities resulting in disproportionate numbers of incarceration for these groups. The police discretion that I began thinking about when writing this piece is guided by a framework called whiteness.

The Duality of Black and Indigenous Enslavement

Black and Indigenous peoples’ histories are often siloed, but it is important to make visible the specificities and uniqueness of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism as connected to land stolen from people and people stolen from land, and of course, thinking about how Black-Indigenous peoples are uniquely affected).

In Canada, slavery as an institution operated from 1671 until 1834 when it was abolished by the British Empire. The abolition of slavery meant the end of formalized legal ownership of Black people in this country, but the segregation of Black people was justified for many years afterward, grounded in ideas about racial inferiority that had been used to justify Black enslavement in the first place (Henry, 2019). A lesser known history is that under French Rule enslaved Indigenous peoples outnumbered enslaved Africans due to the ease with which New France could acquire Indigenous slaves (Cooper, 2006, p. 74-76).

The duality of these histories highlights how, for both these groups, configurations of historical violence in Canada and contemporary practices of over-policing, surveillance, social exclusion, and incarceration rely on classifications of race, gender, class, dis/ability and sexuality.

These configurations have been constituted through colonial relations and white supremacy.

The duality of these histories reflect a parallel familiarity of pain, slaughter, disenfranchisement, and unbelonging. These stories make evident that the experiences of Black and Indigenous peoples are connected to ways in which racism and racialization were and still are central organizing features of the Canadian state, especially through the spectre of incarceration.

Carceral Redlining as a Technology of White(Settler) State Violence

The term ‘redlining’ originated in the 1930’s in the United States, where it was developed by federal housing agencies, local governments, and the private sector to dissuade banking institutions from giving mortgages to specific areas or neighbourhoods (Harris, 2003). The practice involves the literal drawing of red lines around portions of a map to indicate which areas loans should not be made. The systemic practice of redlining has been well documented (see Harris and Forrester, 2003; Solomon, Maxwell and Castro, 2019) as a highly racialized practice impacting the economic viability of Black peoples in the United States.

‘Carceral redlining’ is a concept I developed to refer to the systemic ways in which incarceration practices are operationalized by the redlining of racialized communities as a tool for social control. There are effectively red lines drawn around certain communities criminalized and as such, targeted for incarceration.

I use the term carceral redlining in conjunction with my preference for the term ‘carceral system’ – as opposed to the Criminal Justice system – to denote that the Canadian state is best understood as a tightly woven, comprehensive socio-political network that relies, “on the exercise of state-sanctioned physical, emotional, spatial, economic and political violence to preserve the interests of the state” (BUS, 2019).

This network includes private prison contracts, law enforcement, courts, and any other state faction that financially of politically benefits from the re-inscribing of the convict-lease system, the prison-industrial-complex, predatory racial profiling, and the eventual disproportionate incarceration of Black and Indigenous peoples (BUS, 2019). These constellations of power demonstrate that carceral systems in Canada are intersectional legal enterprises founded upon white supremacy (to preserve the interests of white Canadians) in the making of Canadian nation-building.

Carceral Redlining as fuel for Mass Incarceration

There has been a plethora of literature documenting mass incarceration in the United States (Roberts, 2004; Alexander, 2012; Abu-Jamal & Johanna Fernández, 2014; Sawyer & Wagner, 2019). Yet, lesser known is the impact of mass incarceration on Black and Indigenous populations in Canada.

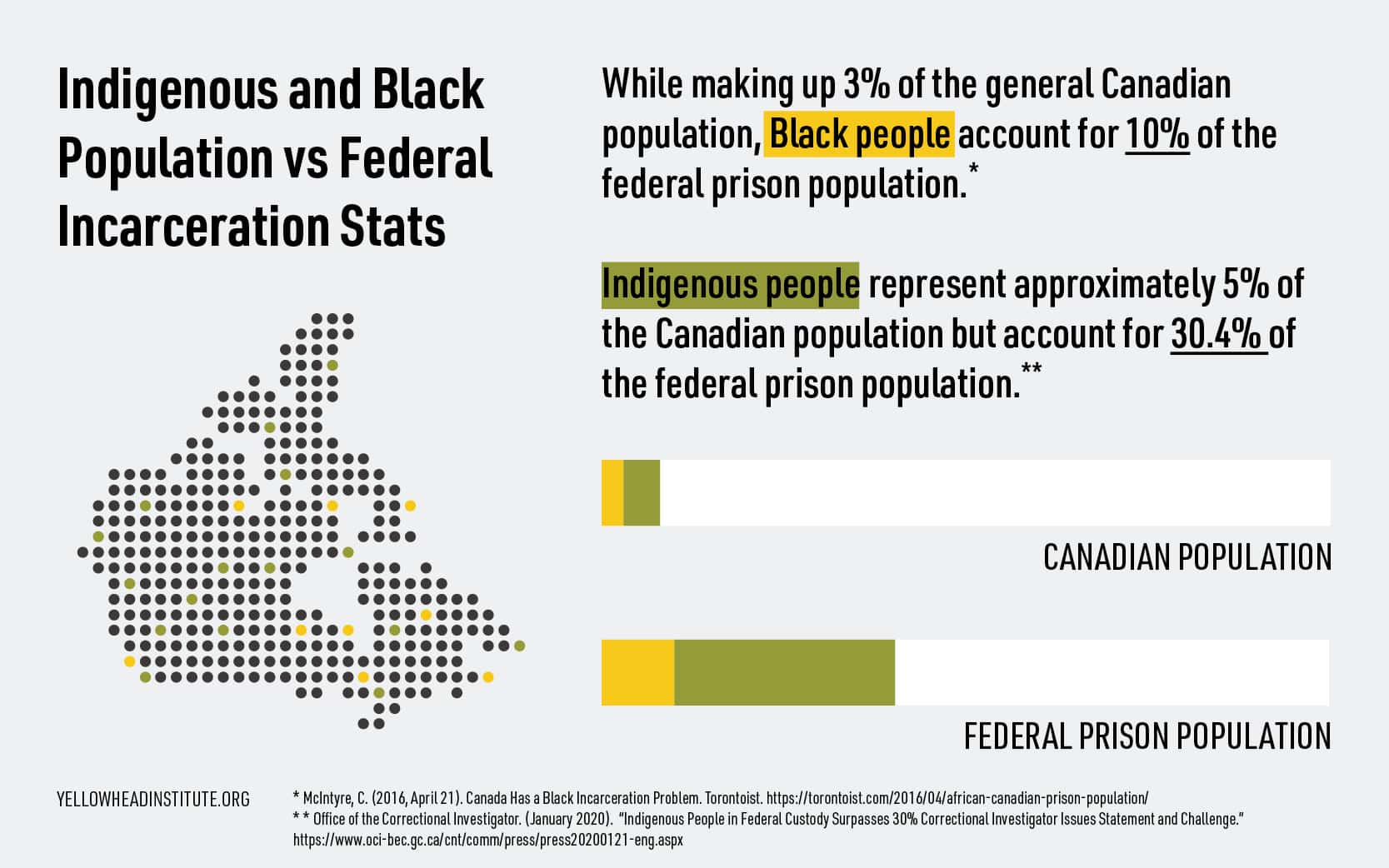

Although Canada’s crime rates have been declining for the past 20 years, rates of incarceration for Indigenous and Black people have increased disproportionately.

Since 2010 incarceration of Indigenous peoples has increased by 43.4% (or 1,265), whereas the non-Indigenous incarcerated population has declined by 13.7% (or 1,549 over the same period (Zinger, 2020). In Manitoba Indigenous peoples represent 16 per cent of the general population account for 70 per cent of the jail population (JHS, 2017).

CARCERAL REDLINING Infographic Series

DOWNLOAD INFOGRAPHICS HERE

Overall in Canada, Indigenous people represent only about 5 per cent of the general population but as of January 2020, they accounted for 30.4 per cent of the overall federal prison population; even more startling is that Indigenous women account for 42 per cent of federally incarcerated women (Zinger, 2020). Black people in Canada have not fared any better. Similar disparities are evident in provincial jails where in Nova Scotia Black people represent 2 percent of the general population but account for 14 per cent of the jail population. While making up 3 per cent of the general Canadian population, Black people account for 10 per cent of the federal prison population and are subject to nearly 15 per cent of all use-of-force incidents (McIntyre, 2016).

Indigenous and Black prisoners have higher security ratings in prison, are overrepresented in segregation and “maxed” out for longer periods of time and are less likely to be paroled. The recent impact of COVID-19 on prisoners in the United States and Canada has brought some attention to prison health, but overall the response has not drawn international attention. Similar to the plight of prisoners during Hurricane Katrina, the vast majority of people in our society view Indigenous and Black people as second-class lawbreakers, who put themselves in jail or prison and deserve to be there, in times of crisis or otherwise.

In order for mass incarceration to take place, systemic practices of exclusion have to be embedded within the fabric of our society. Whiteness as a theoretical framework, and white supremacy as an active ontological practice works to mark spaces and designate most notably, Indigenous and Black bodies as undesirable for nation-building.

One of the most identifiable examples of confinement in Canada is that of residential schools. The whitewashing of conquest in our Canadian history books relies on the language of “assimilation” and “civility” to mask the cruel realty of physical and sexual abuse, and cultural genocide that Indigenous people endured. The Canadian government’s literal redlining of Indigenous communities, by marking and mapping stolen land for the removal of children to sites of displacement, replete with substandard education is indeed a carceral act.

Anti-Indigenous racism has organized Indigenous communities as pathological and in need of surveillance. Indigenous bodies then became marked as “savage,” “unbelonging,” and “degenerate,” thus bodies in need of confinement. Prisons, then, have become a new variation of residential schools.

Similar to anti-Indigenous racism, anti-Black racism as evident through the relational practice of slavery was mapped and marked on Black bodies. Slavery as an institution in Canada was an organized state entity linking Blackness and crime together making way for disproportionate drug arrests, violence, and sex-work related offences in the early nineteenth and twentieth century (Maynard, 2017). Surveying Black bodies through racist immigration policies, child welfare practices, and school segregation were (and continue to be) common practices perpetrated by the Canadian state.

The redlined government sanctioned “ghettos” commonly referred to as “priority neighbourhoods,” provide playgrounds for over-policing practices to flourish within communities socially constructed for economic failure. I am reminded here of Africville, a once thriving Black community in Nova Scotia that was bulldozed by the Canadian government to make way for an infectious disease hospital.

Residential schools and the institution of slavery are spaces of incarceration, displacement and state violence.

Social exclusion practices via the literal and figurative mapping of space and bodies demonstrates how racial exclusion and the violence of forced displacement were carceral processes central to the organizing Canada as a white setter society (Oikawa, 2000).

Towards Prison Abolition

Given the current, global movement towards eradicating anti-Black racism, one of the more hopeful engagements of scholar-activism is unfolding around younger thinkers collaboratively leaning into and learning from each other’s experiences to move towards a politics of prison abolition.

These emergent communities are examining the ways in which discriminatory hiring practices, racial profiling, inadequate healthcare, lack of access to clean water on reserves, school funding-by-postal-code, warehousing children and their parents in immigration cages, warehousing children in the child welfare system, and higher rates of probation and parole breaches for Black and Indigenous folks, are indicative of systems that require dismantling.

The answer to these challenges is prison abolition. Like defunding police, it is not actually a utopian concept – it extends beyond the idea of imagining a world without prisons and is a call to visioning a world where inequalities are resolved by investing in housing, healthcare, and education – all investments that are required for community safety. It is not utopian, but simply fair and just.

We are witnessing a moment in time where the inter-connected histories of Black and Indigenous communities are coming together in contemporary mobilization against state violence. The time has come to dismantle the interlocking systems of power and domination that have been in place for so long in this country.

Endnotes

Abu-Jamal, M. & Fernández, J. (2014). Locking Up Black Dissidents and Punishing the Poor: The Roots of Mass Incarceration in the US, Socialism and Democracy, 28:3, 1-14, DOI: 10.1080/08854300.2014.974983

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: [Jackson, Tenn.]: New Press; Distributed by Perseus Distribution,

Berkley Underground Scholars (BUS). (2019). https://undergroundscholars.berkeley.edu/about

Brown, K. G. (2019, February 18). Canada’s slavery secret: The whitewashing of 200 years of enslavement. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/canada-s-slavery-secret-the-whitewashing-of-200-years-of-enslavement-1.4726313

Cooper, A. (2006). The hanging of Angelique: The untold story of Canadian slavery and the burning of old Montréal. Toronto: HarperCollins.

Harris, R. & Forrester, D. (2003). The Suburban Origins of Redlining: A Canadian Case Study, 1935-54. Urban Studies. Vol. 40, No. 13, pp. 2661-2686.

Henry, N. (2019). Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/racial-segregation-of-black-people-in-canada

John Howard Society of Ontario (JHS). (2017). https://johnhoward.on.ca/

Maynard, R. (2017). Policing Black lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

McIntyre, C. (2016, April 21). Canada Has a Black Incarceration Problem. Torontoist. https://torontoist.com/2016/04/african-canadian-prison-population/

Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2020, January 21). Indigenous People in Federal Custody Surpasses 30%. Correctional Investigator Issues Statement and Challenge. https://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/comm/press/press20200121-eng.aspx

Oikawa, M. (2000). Cartographies of violence: Women, memory, and the subjects of the internment. Canadian Journal of Law and Society / Revue Canadienne droit et société. Vol.15, No. 2, pp. 39-69

Oikawa, M. (2012). Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

Roberts, D. E. (2004). The social and moral cost of mass incarceration in African American Communities. Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/583

Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2019, March 19). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019. https://law.loyno.edu/sites/law.loyno.edu/files/images/Class%202%20US%20Mass%20Incarceration%20PPI%202019.pdf

Solomon, D., Maxwell, C., & Castro, A. (2019, August 7). Systemic Inequality: Displacement, Exclusion, and Segregation: How America’s Housing System Undermines Wealth Building in Communities of Color. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472617/systemic-inequality-displacement-exclusion-segregation/

Citation: Rai, Reece. “Carceral Redlining: White Supremacy is a Weapon of Mass Incarceration for Indigenous and Black Peoples in Canada.” Yellowhead Institute, 25 June 2020, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/06/25/carceral-redlining-white-supremacy-is-a-weapon-of-mass-incarceration-for-indigenous-and-black-peoples-in-canada/