- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CANADA are working to restore their place names and revitalize their languages after colonial policies and law sought to eradicate them. During the last several centuries, huge swaths of Indigenous lands were remapped and renamed by colonial powers, usually by white men. More often than not, places were named according to the whims of surveyors, cartographers, and politicians of the day. This is in stark contrast to the deeply meaningful, personal, and often spiritual naming practices of Indigenous peoples.

With the erasure and replacement of much of the vast catalogue of Indigenous toponyms, only a small fraction of Indigenous place names are today found on “official” maps and signs.

Of course, renaming has been a critical part of settler colonialism generally, which is predicated on the erasure of Indigenous peoples, including their languages, cultures and social structures — any and all evidence of Indigenous peoples’ living presence. Thus, reverting to Indigenous place names in relation to oral histories, Indigenous laws, and languages is part of the process of reclaiming Indigenous knowledge and territories. In this piece we offer several examples of Indigenous nations who are actively reclaiming jurisdiction to their lands, and provide recommendations for how federal and provincial/territorial governments can help to undo some of these past harms and injustices.

History of Settler Renaming Practices

The settler-colonial process of renaming reflected a range of meanings for settlers. Names were sometimes taken directly from Europe, such as the Thames River, which runs through London, Ontario; other places were named after white individuals, like the city of Regina, Saskatchewan; and sometimes after Christian saints, such as Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario. In other cases, Indigenous names continue in some form, though often corrupted, like Wetaskiwin, Alberta, which was derived from the Cree word of wītaskiwinihk or “the hills where the peace was made.” There are also places that were given an English or French name translated from an Indigenous language, like Nose Hill and Medicine Hat in Alberta.

But taken together, the settler colonial landscape is overwhelmingly named by and for settlers, using settler references and languages.

A particularly egregious, but not uncommon, example of the enthusiastic yet arbitrary approach to colonial renaming can be found in the work of the German-Canadian land surveyor Otto Klotz, who mapped large parts of the Canadian West in the late 19th century. Klotz, like many of his contemporaries, believed that Indigenous peoples were subhuman and doomed to extinction. As such, he had no interest in existing place names. He named lakes in the Turtle Mountain area (in Southern Manitoba), for example, after his children, pets, and employees. He also named several mountains in British Columbia after himself, one of which is still known as Mt. Klotz. This kind of narcissistic, disrespectful, and poorly-considered renaming was very much the norm across much of Canada and other settler colonies. These place names continue to define much of the Canadian landscape.

Just as colonial place names and naming practices have helped to construct colonial stories about the land and its inhabitants, Indigenous place names are also powerful vehicles for narrating history and inscribing the landscape with meaning.

Indigenous place names can represent important historical events and legal principles, such as the case with some creation stories. They can convey teachings on how to live in good relations with others and the land. As a number of Indigenous scholars have pointed out, there is a strong connection between the re-establishment of Indigenous place names, and the revitalization of Indigenous languages and cultures.

Sites of Transformation

Indeed, there are several examples of Indigenous communities re-establishing place names in the context of self-government agreements, land use planning and conservation. It is not surprising that this work is being undertaken in tandem with the increasing exercise of jurisdiction regarding lands and resources by Indigenous people. While there is much to discuss around the underlying policy animating this jurisdiction, there are clear and productive opportunities here for the revitalization of place names.

Treaty and Self-Government Approaches

In British Columbia, the Nisga’a Final Agreement changed thirty-four place names from English to Nisga’a language. For example, the town of Greenville became known again as Laxgalts’ap, which translates to “village on a village.” Although, this may seem incidental, it powerfully signifies the continued presence and recognition of the Nisga’a language, laws, and history. As evidenced in the Calder case, hunting and fishing were often at the same village site. The historicizing of place names is part of the modern treaty process and are expressions of Indigenous governance, laws, and reclamation.

In fact, in many modern treaties (the agreements that precede most self-government agreements), First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples have the legal powers to re-establish place names in their “settlement” areas. Under these agreements, they can have their toponyms recognized by provinces or territories, and maps of the areas changed. In some cases, such as the Tlicho Agreement, the Government of the Northwest Territories must consult the Tlicho on any renaming efforts they might undertake.

While some nations are more active in this pursuit than others, it is one mechanism by which Indigenous peoples are revitalizing and re-asserting place names as they work to expand their jurisdiction.

One of the largest and most comprehensive projects of Indigenous place name restoration and cartography is being carried out by the Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee (Cree Nation in Quebec). After decades of intensive work, including the gathering of oral histories and collaborative mapping work with trappers, the Cree Place Names Program now has a sophisticated database with records for nearly 20,000 named places throughout their territory. This database standardizes spellings, includes cultural knowledge associated with places, and includes safeguards for knowledge that is not appropriate to share widely. The project is now at the point where detailed and useful maps can be produced for those working on the land, and project leaders are considering designs for digital platforms. They are also considering approaches that will put Cree place names onto official government maps and signs

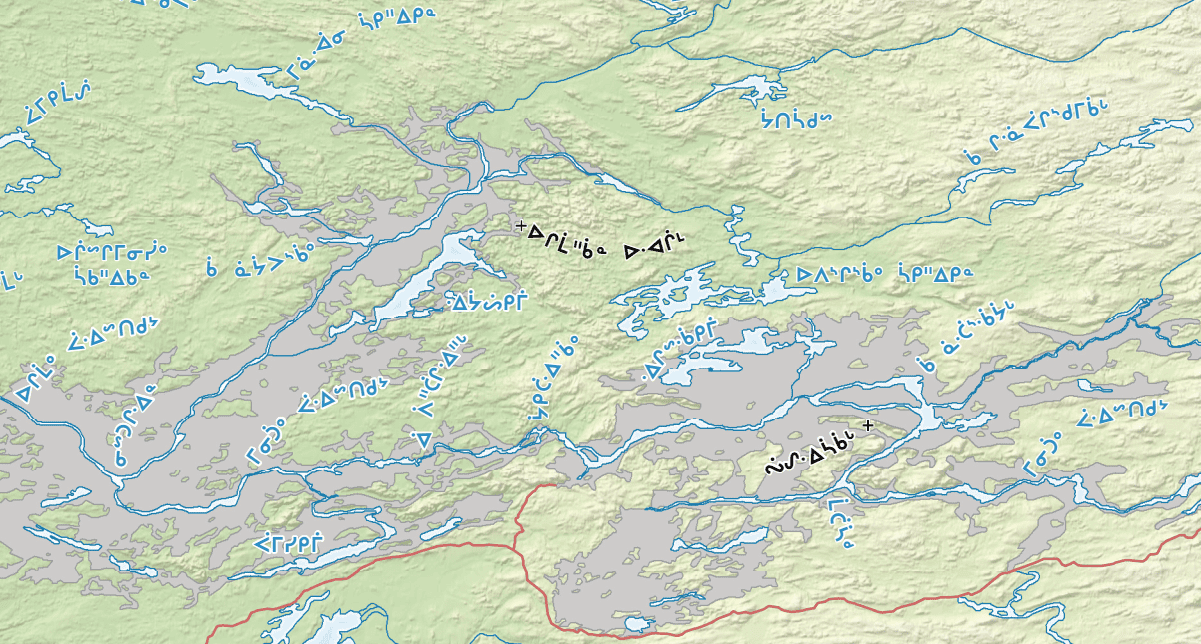

An excerpt from a regional map published by the Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee in 2017. Shaded sections represent areas flooded for due to hydro-electric development. The map thus visually distinguishes natural and artificial waterways in a way that maintains historical memory of the land.

Land Use Planning and Conservation

Indigenous nations have also asserted their territorial jurisdiction through Land Use Plans, especially in the past twenty years or so. For example in 2001, the Squamish Nation developed the Xay Temíxw Land Use Plan: For the Forests and Wilderness of the Squamish Nation Traditional Territory. This Plan seeks to reinforce “the community’s vision for the future of the forests and wilderness of the traditional territory and includes restored place-names to specific sites within the land use planning area, specifically sacred sites.” In an email, Councillor and Spokesperson for the Squamish Nation, Khelsilem stated that the Plan’s purpose was to “identify sensitive and culturally important areas, based on community input. It has since been used to communicate with industry and government and protect large areas of the Squamish Nation’s territory, including harvesting areas, old growth forests, and cultural sites.” The Squamish Nation have led the way in regards to the protection of their territory through critical engagement and education.

Place names can intervene in settler colonialism by animating Indigenous history, reminding people of the ancestors of these lands.

This is strongly exemplified by the Stawamus Chief, an important mountain in the Squamish nation’s territory, which is bisected by the Sea to Sky Highway. This impressive mountain overlooking the Salish Sea in Southern British Columbia holds special significance for the Squamish Nation because it relates to their oral histories and ancestors. The name Stawamus is the anglicized version of St’á7mes, which refers to a village site at the base of the mountain. The mountain’s names known as Siy̓ám Smanít to the Squamish, meaning Highly Respected Mountain or Smánit tl’a St’á7mes (Mountain of St’á7mes).

The Squamish Atlas, an on-line and comprehensive place name database, shares the oral history relating to man named Xwechtáal who fought for many years with Sínulhḵay̓ or two headed serpent and finally killed it. The Sínulhḵay̓ is seen along the side of the wall and brought to the forefront in the years prior to the 2010 Olympics when new signs in the language were placed along the Sea to Sky Highway. The formerly known ‘Chief’ had a new sign put up for the ‘Stawamus Chief’. This was as a result of consultations between the provincial government and the Squamish Nation.

The Thaidene Nëné (the Land of Our Ancestors) Agreement is another example of how Indigenous jurisdiction is being enacted by Indigenous nations in the context of co-management agreements. This Agreement was signed between the Łutsël K’é Dene, Deninu K’ue, and Yellowknives Dene with the Government of the Northwest Territories and Parks Canada. Covering a total of 33,690 square kilometres, it is one of the largest protected areas in the world, including a national park and conservation area. It protects important sites from diamond and uranium mines. Within this area is the T’sankui Theda or the “Lady of the Falls,” in the Chipewyan or Dënesųłiné language, a sacred place that runs along the East Arm of Great Slave Lake.

In an era of intense climate change, protecting the land for future generations is important, and this type of co-management conservation agreement is one way in which Indigenous nations have chosen to take actions to preserve their culture, land, and place names.

Institutionalizing Revitalization

The recently passed Bill C-91, An Act respecting Indigenous Languages, (as passed by the House of Commons 9 May 2019) is an important step toward funding Indigenous language revitalization on numerous fronts. Of course there are still many issues with the Act, including that it does not address the re-establishment of Indigenous place names.

This Act primarily focuses on program or service delivery, but this Act could also assist in the language revitalization process through providing Indigenous nations with the ability and funding to create policies in regards to re-naming in their own languages. For example, the Act states:

5 (c) Establish a framework to facilitate the effective exercise of the rights of Indigenous peoples that relate to Indigenous languages, including by way of agreements or arrangements referred to in sections 8 and 9;

and

5 (d) Establish measures to facilitate the provision of adequate, sustainable and long-term funding for the reclamation, revitalization, maintenance and strengthening of Indigenous languages.

If taken seriously, this could mean that Indigenous languages would become more relevant, spoken, and reflected in our world. It could mean that this Act would be a means of more meaningful engagement beyond that strictly relating to services and programs.

There’s still much more work to be done in regard to reclaiming place names as a part of re-establishing Indigenous jurisdiction.

The examples we have given also show how Canadian governments, at all levels, can work with Indigenous nations to facilitate their work. Thinking more strategically on this point, we have developed a number of recommendations for policymakers to take up in order to more genuinely support the revitalization of Indigenous place names.

Four Recommendations:

- Empower Indigenous government bodies to create public policies and processes that lead to the recognition of Indigenous place names;

- Recognize the connection between language and land by including place name initiatives in federal, provincial, and municipal policies, maps, and signs related to Indigenous place names;

- At all levels, work with the local Indigenous nations to re-establish Indigenous toponyms and respect Indigenous jurisdiction and priorities concerning these matters; and;

- Provide funding to Indigenous Indigenous nations in their initiatives regarding Indigenous place names.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for information and assistance provided by John Bishop (Toponymist, Cree Nation Government), Khelsilem (Councilor and Spokesperson, Squamish Nation), Agnes Huang (Barrister & Solicitor, Saltwater Law), and Benjamin Ralston (Lawyer, PhD Candidate and Lecturer, University of Saskatchewan College of Law).

Citation: Gray, Christina and Daniel Rück. “Reclaiming Indigenous Place Names.” Yellowhead Institute, 8 October 2019, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2019/10/08/reclaiming-indigenous-place-names/

Brief feature image is of the Siy̓ám Smanít / Stawamus Chief; photo taken by Erick Calder.