- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC lays bare the vast differences in people’s abilities to maintain physical and social distance across the country. The housing, water, community and health infrastructure deficits on First Nation reserves create ideal conditions for the transfer of viral infection. They impact people’s ability to social distance, wash hands, access vital equipment, access supplies and receive adequate health care. Reports today signal 15 Indigenous communities have cases of the novel coronavirus and that number is likely to grow.

Echoing the events of a century ago, when the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic decimated First Nations communities across the country, this is a crisis that will be defined by three factors: pre-existing divides; the extent to which those in political power are held to account for upholding them; and our ability to seize the moment to transform them.

Gina Starblanket and Dallas Hunt point out in a recent opinion piece that Canada’s “vulnerability” to the crisis was first defined as a medical emergency before gradually becoming an economic crisis.

It is clearly both in First Nation communities because the medical emergency is built on a pre-existing economic crisis of deep inequality, racism, colonization, and systemic underfunding.

For example, the community of Kashechewan in the James Bay floods every year due to their relocation in the 1950s by the Canadian government onto a flood plain. When the community floods, residents must be evacuated to Thunder Bay, but this year they face an additional crisis due to the city’s lack of capacity in the face of COVID-19. The City has openly stated they cannot support members from remote communities, leaving Kashechewan to scramble for alternatives.

Now is a time for advocates to arm ourselves with knowledge about the discretion, expedience, and politics of poverty in Canada.

Why is there never enough money for boil water advisories on reserves to be lifted, but $82 billion can appear almost instantaneously to support Canadians in crisis?

What are the infrastructure deficits on reserves? How much would it take to fix them? How can this be done in a way that empowers Indigenous jurisdiction and governance?

This Brief examines the recent commitments from the federal government in relation to the existing information about infrastructure deficits in First Nations. Specifically, how do the “shelter in place” requirement to slow down the pandemic – by starving the virus of hosts to infect – align with needs’ assessments of housing, water, and health services in First Nations?

Federal Relief for First Nations facing Covid-19

Capitalists never let a good crisis go to waste. In Alberta, for example, billions have been committed by the provincial government to backstop the inevitable slide to bankruptcy faced by a dying energy sector. Flailing and mismanaged industries, like airlines, are going cap-in-hand for public monies. The federal government has also disregarded strategies of boosting government resources like Canada Post, in favour of entering into agreements with multi-national companies like Amazon.

Mere weeks after announcing they were withdrawing their application for the Teck Frontier mine project in Alberta, TC Energy was back in the news. With an investment of $1.1B of public funds, acting as a huge corporate bail-out, TC Energy is prepared to re-ignite the Keystone XL project which would send bitumen from Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico.

Seemingly gambling on a return to previous oil prices, or ignorant to the facts that Western Canadian Selects have fallen to as low as $5/barrel, this investment perpetuates a trend started by the provincial government with its investment of retirement funds in Coastal Gaslink.

Meanwhile, the funding package committed federally for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit is a fraction of that cost. Two different funds have been announced to address COVID-19 for First Nations. The first is a $100 million dollar federal fund to cover public health needs for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis communities. It appears to be an emergency fund to address primary care gaps like Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and tests. There is also a $305 million dollar Indigenous Community Support fund that is meant to “respond to identified needs to update and/or activate pandemic plans”. It includes medical transportation, the adaptation of community infrastructure, and “on-the-land initiatives to support social isolation or food security.”

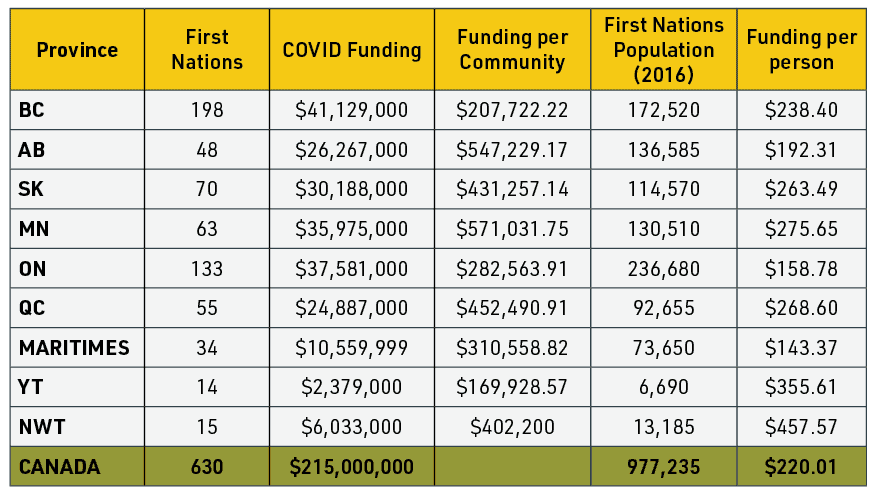

This chart represents funds made available by Indigenous Services Canada for this Indigenous Community Support Fund. $215 million of that Fund has been designated for First Nations and divided by province and territory. Funds are expected to be spent on support for Elders and vulnerable community members, food insecurity, educational, mental health, among other issues. More information can be found here.

Ontario announced a $37 million provincial fund for Indigenous communities on April 7, 2020; additional provincial/territorial funding has yet to be revealed. As recently outlined in government messaging, the relief fund is being distributed depending on the usual government indicators of population, remoteness, among others. This means that different regions will receive different amounts, creating a varying impact of the relief fund across communities. The chart makes the assumption that First Nations will be helping all members, however it is not clear if off-reserve populations will be supported with these funds. However, some funding has been allocated specifically for urban communities.

Upon further analysis, the funding would amount to an average of $220 per First Nations person, if distributed based upon population. If this one-time payment is intended to help First Nations and their members deal with the immediate impacts of COVID-19, it appears as though the support falls short when compared to other mechanisms announced like the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) which will give Canadians $2000 per month for four months.

Compared to the $82 billion being made available to assist Canadians and businesses during this difficult time, as outlined by Grand Chief Billy Morin of Treaty 6, the $305 million earmarked for Indigenous peoples represents 0.003% of funding being offered.

If a population indicator was utilized for the distribution of government relief, the allocation to First Nations would equal just over $4 billion.

A stark reminder on how government support and relief do not follow usual conventions when applied to First Nations and their communities.

This discrepancy in available support further highlights the piecemeal, incremental and insufficient approach to First Nations issues undertaken by the Liberals, and a real disconnect within the government and bureaucracy as to the actual needs of First Nations communities.

What are the infrastructure needs on First Nations reserves?

According to the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, the infrastructure deficit across First Nations in Canada could be between $25-30 billion. The Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples (SSCAP) released a report in which Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) calculated that the cost of meeting the immediate infrastructure needs on reserve would escalate to $9.7 billion by 2018. So, there is little consensus on what the true infrastructure deficit on-reserve may be, but one can conclude that investments outlined to date have little impact on the $8 – 30 billion shortfall.

But rather than fill this gap, instead, Canada has been sitting on its hands. The SSCAP reports shows that despite $300 million set aside by Canada in a trust fund for the First Nations Market Housing Fund in 2008—which was supposed to build 25,000 new homes in 10 years—only 99 homes were built by May 2015. In a tacit acknowledgement of this lack of infrastructure, the federal government’s initial plans for a First Nation specific response to COVID-19 was the erection of isolation tents or field hospitals in some of the most inhospitable places

If we look at progress on Boil Water Advisories, there are at least 61 that have yet to be lifted, with promises from the Trudeau government they will all be lifted by 2021. Reports by independent researchers, however, show much higher numbers, for example, 127 in BC alone.

The lack of proper infrastructure plays a huge role in Indigenous homelessness and people not being able to return to their communities. This compounds their ongoing vulnerability, and especially places women, trans, Two Spirit and non-binary people at greater risk.

In the best of times, access to goods can be difficult to obtain on reserve, which tends to lack commercial infrastructure, forcing communities to engage in retail in neighbouring municipal communities. The idea of sheltering in place is not an option when the band gas station is the only source of food, pushing people into the city. As well, the convenience of food and grocery delivery is almost non-existent unless a community borders a city or town. Even then it is unlikely many businesses will deliver to a reserve, many without an address system.

Investment not Bailouts

It is inevitable that a brutal austerity program will kick in when the pandemic is over and business resumes. Once again, First Nations will be at the back of the line demanding money for basic investments. That must change. If the pandemic shows us anything, it is that lack of basic infrastructure compounds disaster, that resilience planning depends on constant care, and that money is always available when the emergency hurts those deemed unexpendable.

Instead, Canada should support a new infrastructure of the future. And it must begin by addressing the urgent infrastructure needs in First Nation communities today.

Some of these immediate needs are identified in a petition circulating and spearheaded by Chief Isadore Day and others that calls for urgent enhancement of healthcare capacity in communities, the deployment of Cuban doctors onto Manitoba reserves, equipment for the Canadian rangers stationed in communities, and rapid distribution of protective equipment, tests, ventilators, and field hospital materials.

This would be a good start. But the end must be the massive investment of infrastructure in Indigenous communities across the country. Not only to clear the tremendous backlog from decades of under-funding, but to chart a new future for development on-reserve. So that the courage, vision, grief, panic, and fear of infection experienced by leaders right now as they prepare once again to fight for equal access to basic human needs, in the face of a global pandemic, never ever happens again.

Citation: Pasternak, Shiri and Houle, Robert. “No such thing as natural disasters: Infrastructure and the First Nation fight against COVID-19.” Yellowhead Institute, 9 April 2020, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/04/09/no-such-thing-as-natural-disasters-infrastructure-and-the-first-nation-fight-against-covid-19/