- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

THIS AUGUST 5TH, Kashmiris mark and mourn the one-year anniversary of the “official” annihilation of their autonomy.

Kashmir’s absorption by India following Partition was only ever partial and provisional, pending a plebiscite to determine the will of the people that never took place. That was more than seventy years ago. The decades of crushing military occupation and colonial constitutionalism by India that followed eviscerated Kashmir’s independence to an “empty shell.”

Last August, the far-right Indian government stripped away the last remnants of the shell altogether, illegally abrogating the constitutional provisions (Articles 370 and 35A) enshrining Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status.

Since then, the naked rapaciousness of India’s colonial project in Kashmir has been on brazen display: buying up land, selling off rivers and forests, and encouraging demographic flooding by settlers. The Kashmiris themselves have been put under suffocating lockdown.

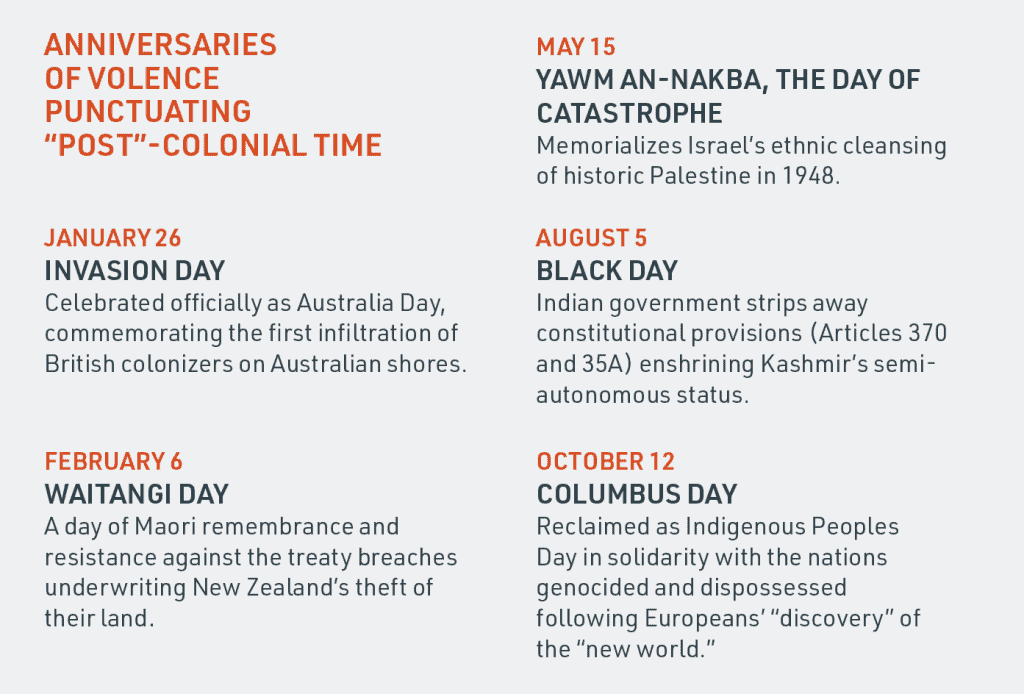

August 5 now joins the list of anniversaries of colonial violence punctuating “post”-colonial time. January 26: Invasion Day, celebrated officially as Australia Day, commemorating the first infiltration of British colonizers on Australian shores in 1788. February 6: Waitangi Day, a day of Maori remembrance and resistance against the treaty breaches underwriting New Zealand’s theft of their land in 1840. May 15: Yawm an-Nakba, the Day of Catastrophe, memorializing Israel’s ethnic cleansing of historic Palestine in 1948. October 12: Columbus Day, reclaimed as Indigenous Peoples Day in solidarity with the nations genocided and dispossessed following Europeans’ “discovery” of the “new world” in 1492. These dates signify enduring structures, not isolated events – the markers of a settler-colonial present maintained by perpetual brutality. There are the quick violences of killing, maiming, torture, and rape, and the slower violences of deprivation of freedom, clean water, healthy land, and food. As Kashmiri scholars, Samreen Mushtaq and Mudasir Amin write, “5 August was not a beginning, not a diversion, not a rupture,” but the extension of seventy years of mass killings, mass blindings, mass torturings, mass disappearances, mass incarceration, and mass rape.

In Canada, the legalized invasion of Indigenous lands for corporate profits continues, with state-sanctioned large-scale resource development projects such as the Trans-Mountain and Coastal GasLink pipelines and the Site C Dam, to name just a few. For Palestinians, too, the nakba – catastrophe – is not a historic memory but ongoing reality, with Israel now preparing to crystallize decades of apartheid rule by formally annexing occupied Palestinian land. Israeli settlers are known to dump sewage on Palestinians, and Indigenous communities in Canada are disproportionately affected by toxic and hazardous waste: the most literal manifestations of what anthropologist Ghassan Hage calls “colonial rubbishing,” the treatment of colonized peoples as surplus populations to be disposed.

In the face of this unpalatable reality, the fiction of a post-colonial world is sustained with a set of common discursive tricks.

How to Cover (Up) Settler Colonialism

1) Overwriting Indigenous histories and geographies

In Kashmir, the Indian government has started removing Kashmiri place names and replacing them with Hindu and Indian nationalist appellations instead. This follows in the tradition of European and Israeli colonizers before them, who exerted domination over Indigenous space by imposing their own maps, land surveys, and names. “We are obliged to remove the Arabic names for reasons of state,” said Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion. Genocide – destruction of a people as a people – is undergirded by epistemicide – destruction of their knowledge and the languages that carry it.

The colonization of space is also a colonization of time. By deleting the past, colonial regimes attempt to delete the possibility of a different future, projecting their constructed “facts on the ground” as eternal truths.

2) Erasing Indigenous sovereignty

The colonial legal fiction of terra nullius is supposedly a relic of the past, yet the underlying negation of Indigenous sovereignty – rooted in this notion of empty land – lives on.

Israel, for example, insists that the Palestinian West Bank is not occupied because “the West Bank had no prior legitimate sovereign” – nothing but terra nullius by another name. In recent decisions, Canadian courts maintain that the settler government “does not require the consent or non-opposition of First Nations and Indigenous peoples before projects [on their lands] can proceed,” not even bothering to square this perspective with Indigenous rights to free, prior, and informed consent under international law. Kashmir, in the dominant state-centric framework, is reduced to an “internal matter” in Indian politics or a “bilateral issue” between India and Pakistan. The Kashmiris themselves, and their self-determination rights, might as well not exist.

3) Representing Indigenous responses to violence as violence itself

Indigenous rights to sovereignty having been obscured, Indigenous struggles for justice are depicted as the source of belligerence rather than the response. “It is easy to blur the truth with a simple linguistic trick,” as the Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti observed. “Start your story with ‘Secondly,’ and the world will be turned upside-down … It is enough to start the story with ‘Secondly’ for my grandmother, Umm ‘Ata, to become the criminal and Ariel Sharon her victim.”

In the inverted colonial version of history, the “cycle of violence” starts with the resistance to invasion and dispossession, not the acts of invasion and dispossession themselves. And so the occupying Indian army becomes the victim of aggression by “Kashmiri militants,” and Israel’s grossly one-sided military assaults on the besieged Gaza Strip become acts of “self-defence.” Indigenous land and water defenders resisting their ongoing mass dispossession at RCMP gunpoint become the “radicals,” and Canada the innocent “hostage” of their blockades.

4) Colonizing the language

The physical assaults on the colonized are accompanied by an assault on the language necessary to describe them. In Canada, journalists widely dismissed the conclusion of a national inquiry that Canada’s policies towards Indigenous peoples legally constitutes genocide, with some insisting that a “new word” other than genocide should be invented. Under the Trump administration, the US State Department now refuses to refer to Palestinian territories as “occupied” in its annual human rights reports.

The legally-accurate terms for colonial practices – occupation, apartheid, genocide – are gradually scrubbed from the vocabulary, the words perversely deemed more offensive than the crimes they describe. Colonization instead goes by a variety of other names, such as “development,” “empowerment,” “humanitarianism,” “counter-terrorism,” “reconciliation,” “liberation,” “saving women,” and “winning hearts and minds.”

Even professed critics of these regimes engage in such linguistic obfuscations, demonstrating the trans-partisan investment in colonial myth-making. The platform of US Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden excludes the word “occupation” when referring to Palestine. Similarly, well-known Indian opposition politician Shashi Tharoor opined that “the West Bank analogy [for Kashmir] is wrong” because “Kashmir is not ‘occupied territory’ but ‘disputed territory.’” In fact, the International Court of Justice has previously held that a territory can be both disputed and occupied at the same time.

5) Pathologizing resistance

The war on language makes language into a weapon of war. Mohawk, Kashmiri, and Palestinian protesters are demonized and criminalized as “terrorists” for burning tires or throwing stones. Meanwhile, the occupation soldiers who brutalize them are extolled as “peace patrons,” “brave security personnel,” and even, in the case of Israel, “the most moral army in the world.”

Between 1967 and 2017, headlines in major US newspapers referred more than twice as often to Palestinians’ “terrorism” as to the occupation that terrorizes them. Likewise, in the year preceding annexation, the New York Times featured four times as many headlines about Kashmiri “militants” as India’s occupying military – in inverse proportion to their respective presences on the ground, where there were around 200 militants (according to India’s own figures) but 700,00 Indian soldiers, a larger deployment than the US army sent to occupy Iraq.

As the regular state murder and assault of unarmed Indigenous people in Kashmir, Palestine, and Canada attests, the very existence of the colonized on their own land is construed as a threat. Canada surveils and jails Indigenous land defenders, including elders, for violating corporate injunctions and other non-violent “crimes” against the colonial property regime; for example, Nehiyaw legal theorist Sylvia McAdam was prosecuted for building shelters on her own land.

In Kashmir, journalists, political leaders, and lawyers are among the thousands who have been detained under India’s Public Safety Act: a “lawless law” that permits detention without trial for up to two years. On July 30, Israel arrested the coordinator of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign, Mahmoud Nawajaa, who joins the 4700 Palestinian political prisoners currently caged in Israel’s mass incarceration system. Under Israeli law, support for BDS – the paradigmatic form of non-violent resistance – is a civil offence.

6) Fetishizing the rule of law

Colonial states’ proclaimed adherence to the “rule of law” is no virtue, when law itself is an instrument of colonial rule. Palestinian human rights organization Adalah has compiled a database of 65 discriminatory laws holding the Palestinians under Israel’s boot. In Canada, the legal apparatus of dispossession has recently been augmented with laws protecting “critical infrastructure” like pipelines – punishing the Indigenous defenders protecting the far more critical infrastructure of land, water, and air. Tellingly, when the Prime Minister was asked about the Shutdown Canada movement, sparked by the RCMP invasion into Wet’suwet’en territory, he responded that he was “concerned about the rule of law.”

In Kashmir, new changes to the domicile law facilitate the current influx of civilian and military settlers, while Kashmiris themselves risk losing their residency rights if their documentation is deemed inadequate. As in Canada and Palestine, law in Kashmir serves as a medium of bureaucratic genocide: the disappearing of a people through erasure of their legal status.

The Other Facts on the Ground

The connections between the colonial projects of Canada, Israel, and India continue to be cemented: through multi-million-dollar arms deals, joint police and military trainings, shared propaganda tours, and diplomatic support for international legal impunity.

In the face of this transnational solidarity between settler regimes, the peoples they subjugate exercise their own. Indigenous delegations from Turtle Island to Palestine; solidarity statements and protests drawing the connections between oppression in Canada, Palestine, Kashmir, and beyond; the sharing of resistance strategies – these are some of the practices of an anti-colonial international relations from the undersides of colonial sovereignty.

The perpetual infusion of violence required to sustain settler rule is a sign not only of its brutality, but also its instability.

Secwepemc warriors continue to build houses in the path of colonial pipelines; Palestinians continue to plant olive trees on their ancestral lands in defiance of their dispossession by the settler state. Kashmiri graffiti punctures occupied space with calls for azaadi (freedom); Anishinaabemowin guerilla street signs remind Canadian settlers we are on Indigenous land.

Anniversaries like August 5 are a reminder, too: that there was a time before the settler colonial present. And there can be a future after it.

Citation: Kanji, Azeezah. “A How-To Guide for the Settler Colonial Present: From Canada to Palestine to Kashmir.” Yellowhead Institute, 5 Aug. 2020, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/08/05/marking-the-settler-colonial-present-from-canada-to-palestine-to-kashmir/