- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

JORDAN RIVER ANDERSON, a child from Norway House Cree Nation who was born with multiple disabilities, has become a name synonymous with government neglect of First Nations children.

As a result of colonial policy and discriminatory payment processes between the Province of Manitoba and Government of Canada, Jordan’s needs were pushed to the side while governments played hot potato; neither level of accepted responsibility for his at-home care.

Jordan would go on to spend his short life in hospital, never returning to his loving home, another Indigenous life cut short through institutionalization. Following his tragic death due to this neglect, advocates and champions, including Dr. Cindy Blackstock from the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society (FNCFCS), sought to ensure that children would never have to face the discriminatory treatment that Jordan endured.

Out of this struggle came Jordan’s Principle, a political and legal thorn in the side of Canada.

This Child-First Initiative is intended to remove barriers by addressing costs for all public services Indigenous children require, whether they reside on or off-reserve, with governments handling billing issues in the background.

Despite the emergence of this critically important Principle, a decade of legal battles ensued, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) ultimately ordering the Government of Canada to fully implement the spirit of the Child-First initiative within it’s full scope and meaning.

But since this ruling in 2016, the Federal Government has continued to interpret the CHRT ruling in alignment with current policy mandates with modest changes.

Troubling Trends in Implementation

Based upon the initial CHRT ruling, and many subsequent rulings, some principles have been established for the federal government regarding Jordan’s Principle submissions from parents and caregivers of First Nation children. These principles include substantive equality (ensuring that all children receive the same levels of care), the provision of culturally centred services, and maintaining the best interest of the child.

Five years into the establishment of Jordan’s Principle, its application and definition at a Federal level, it is past time for an examination of how these principles are being adhered to, and appropriately applied.

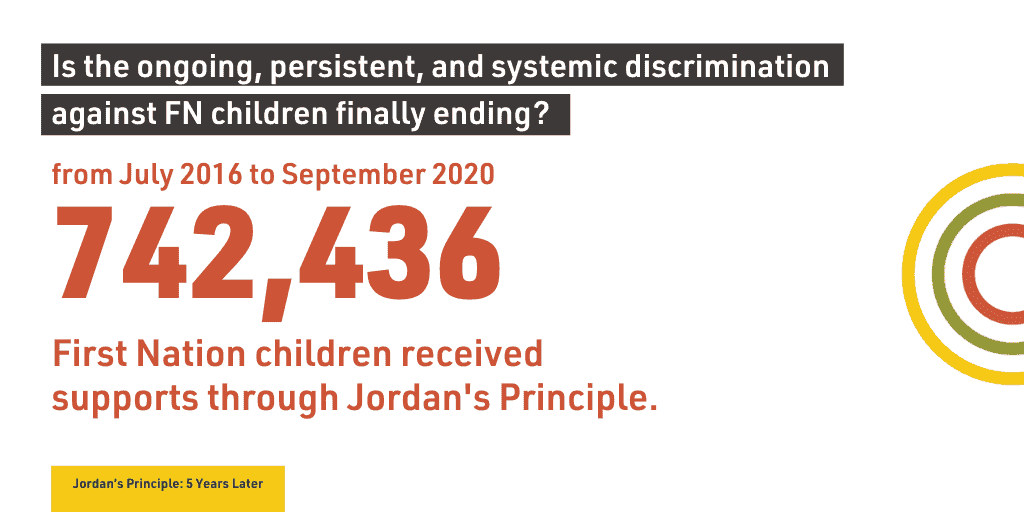

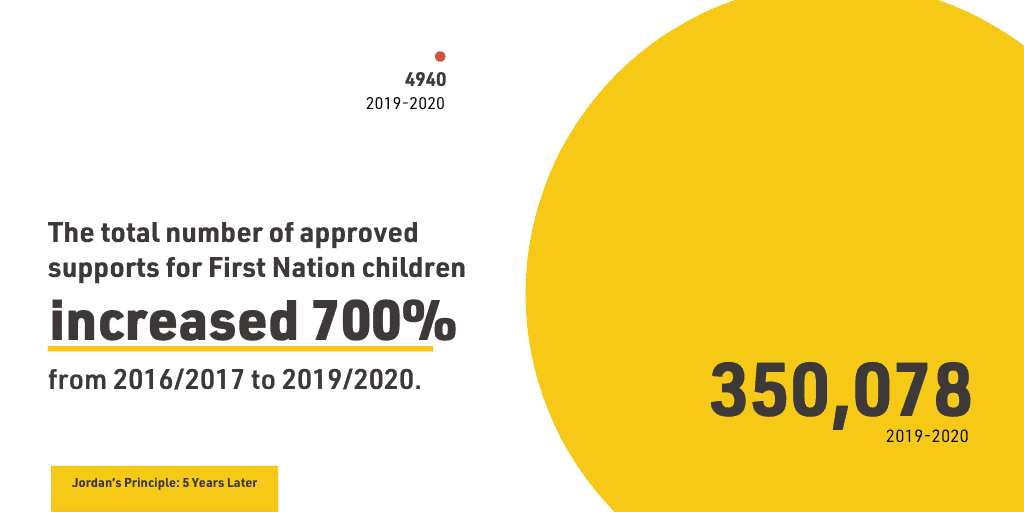

According to the Indigenous Services Canada site, to date, 742,436 “products, services and supports” have been provided to First Nations children across Canada. Additional data, provided by Indigenous Services Canada, further breaks down the approvals by region. These submissions are received from various sources, and ultimately divided into individual or group requests at the departmental level. Upon examination of the data above, a dismal 4900 submissions were approved in 2016/17, followed by an exponential growth over the next four years.

This approval rate is definitely a positive, however should also be viewed with some scrutiny. The fact that Jordan’s Principle, which is intended to ensure that First Nations children receive equitable treatment and avoid jursidictional limbo, has been accessed close to a million times over five years should raise alarms around ongoing, persistent and systemic discrimination. It appears as though Jordan’s Principle support from the federal government is just another band-aid solution and catch-all for the needs of Indigenous children. This incredibly high application rate should also be viewed as a failure of government leaders and decision makers to effectively change how programs and services are delivered to First Nation children.

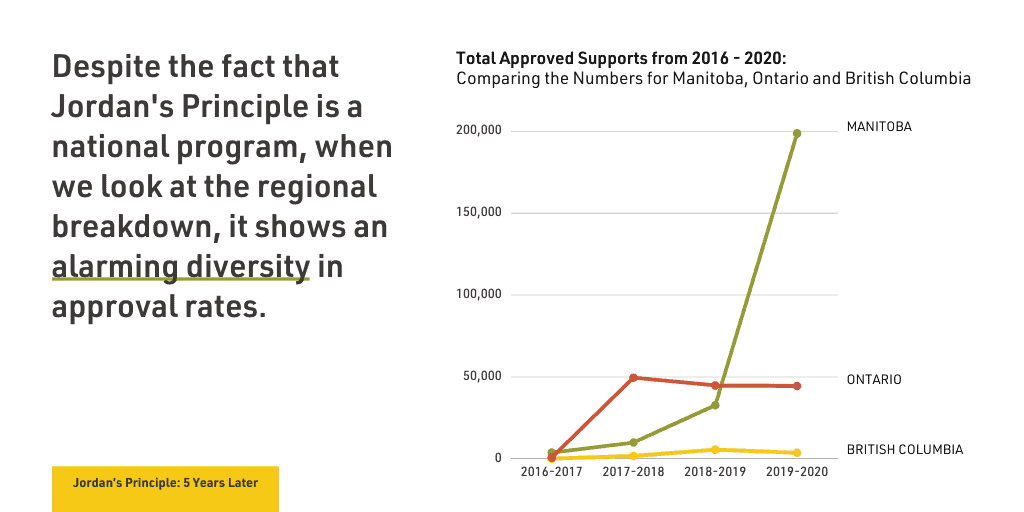

Equally alarming is the diversity that exists when examining the data through a regional lens. Approvals range from a low of 11,977 in British Columbia, to a high of 249,481 in Manitoba over the five years in existence. For a program national in scope and required by the CHRT, it is surprising how much room there is for the ambiguous application of Jordan’s Principle and the implementation of its principles.

Regional Decisions and Discrepancies

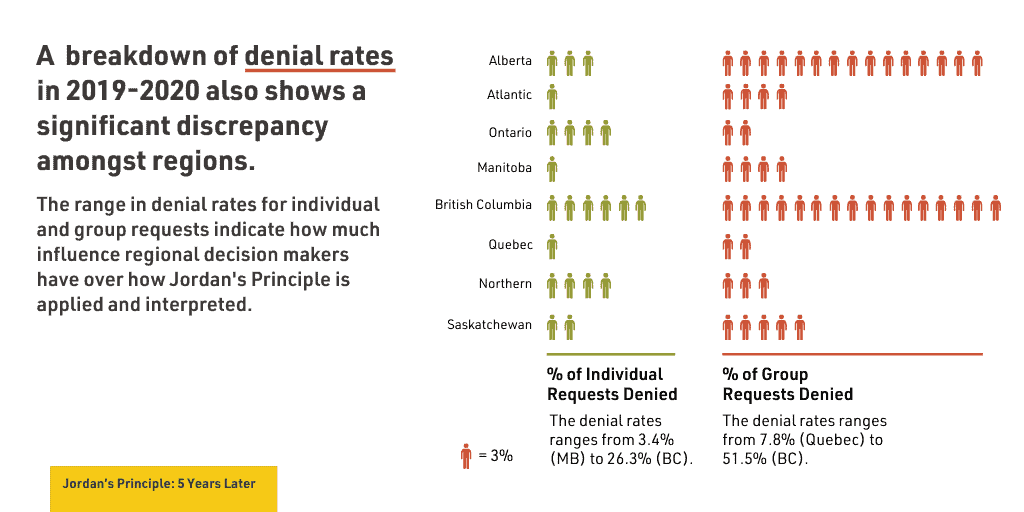

This ambiguity comes into greater focus when exploring the denials of both individual and group requests. With further information obtained from Indigenous Services Canada around application denials for the 2019/20 year, there appears to be significant regional discretion in approval and rejections. While approximately ten per cent of individual requests were denied nationally, a regional breakdown reveals that denials range from 3.4 to 26.3 per cent.

Regional decision makers seem to be playing a huge role in how Jordan’s Principle is being applied and interpreted.

Additionally, internal departmental sources shared that individual interpretation, systemic racism and inherent bias may be playing a role in how requests for assistance from Jordan’s Principle are being approved or denied. If questions exist, or uncertainty around a submission linger, then regional decision-makers escalate requests to national levels, which almost always result in a denial.

When we go a step further and examine the group submission data, the denial rates become even more troubling. Nationally, 18 per cent of group requests were denied in 2019/20, with denial rates ranging from 7.8 per cent to a staggering 51.5 per cent. In Alberta alone, which has the fourth lowest cumulative approval numbers overall, an unfathomable 820,208 supports have been denied. Although it has been clarified by ISC that the 820,000 products or services were from one organization and numerous submissions, it is still troubling that the department has denied more services in one year, from one region, than they have approved in 5 years nationally.

A Narrow Interpretation of Human Rights

What can be done moving forward? When governments utilize existing positions and decision-making authorities for new programs and services, it is very often that established processes corrupt or influence the new programs. New policy paths are difficult to chart. This very much seems to be the case with Jordan’s Principle.

For years, First Nations people have raised issues with the First Nations Inuit Health Branch, Non-Insured Health Benefits and in the case of Alberta, Administrative Reform Agreements. What these out-dated and discriminatory programs and policies do is ensure that the education and health rights, granted through Treaty and Section 35, continue to be narrowly applied and interpreted.

By continuing to ignore CHRT rulings and the calls of Indigenous families and advocates, Canada and the provinces fail Indigenous children.

The approvals and denials become less of a child-first application, and more of a programming failure band-aid. In terms of Jordan’s Principle, this reality means that children will continue to be placed in precarious positions and denied equitable treatment in this place we call Canada.

Citation: Iamsees, Creezon. “Jordan’s Principle 5 Years Later: A Band-Aid for Government Neglect?” Yellowhead Institute, 14 December 2020, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/12/14/jordans-principl…vernment-neglect/

Image by Seth Arcand