- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- The Rematriation of Indigenous Place Names

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

As I began undertaking this year’s budget analysis, I revisited the questions I had been asking in previous years’ analyses. They were always along the lines of, “What would be a ‘good’ budget? Were there any elements that I could support? Can anything be enough?”

These questions — and the need to ask them — continue to bother me because, I think, they’re meant to insinuate that I, that Indigenous people generally, ask for too much. It feels like we have been conditioned to be grateful.

Certainly, I receive feedback from Canadians asking me, “Why can’t you be grateful that Canada gives you any budget allocation at all?” Even as I know (and they should too) that those dollars come from revenue extracted from and generated on our lands.

I could say, and justifiably so, that no budget is satisfactory short of committing to pay back the trillions of dollars Canada has collected at Indigenous people’s expense over the past 200 or so years. However, this is not the basis on which I have undertaken my evaluations.

Instead, the following four points constitute, in my mind, the main questions (or standards) we should consider to determine if we’ve seen a “good budget”:

- Responsiveness: Do investments meet the demands made by Indigenous leaders and experts to bridge long-known gaps in funding?

- Accessibility: Are dollars, wherever possible, made directly accessible to Indigenous people or organizations? Or are they made out to government departments and agencies to be further distributed at the pleasure of some assistant deputy minister or regional director?

- Depth: Can the investments made be categorized as symbolic or otherwise presently immaterial (i.e. providing funding for a committee or plan, where acting on the outcomes from that body would require additional, yet unseen dollars)? Or do they directly intervene in the everyday lived realities of Indigenous people?

- Affirming Self-Determination: Do investments support pathways for Indigenous capacity-building on their terms?

Overview

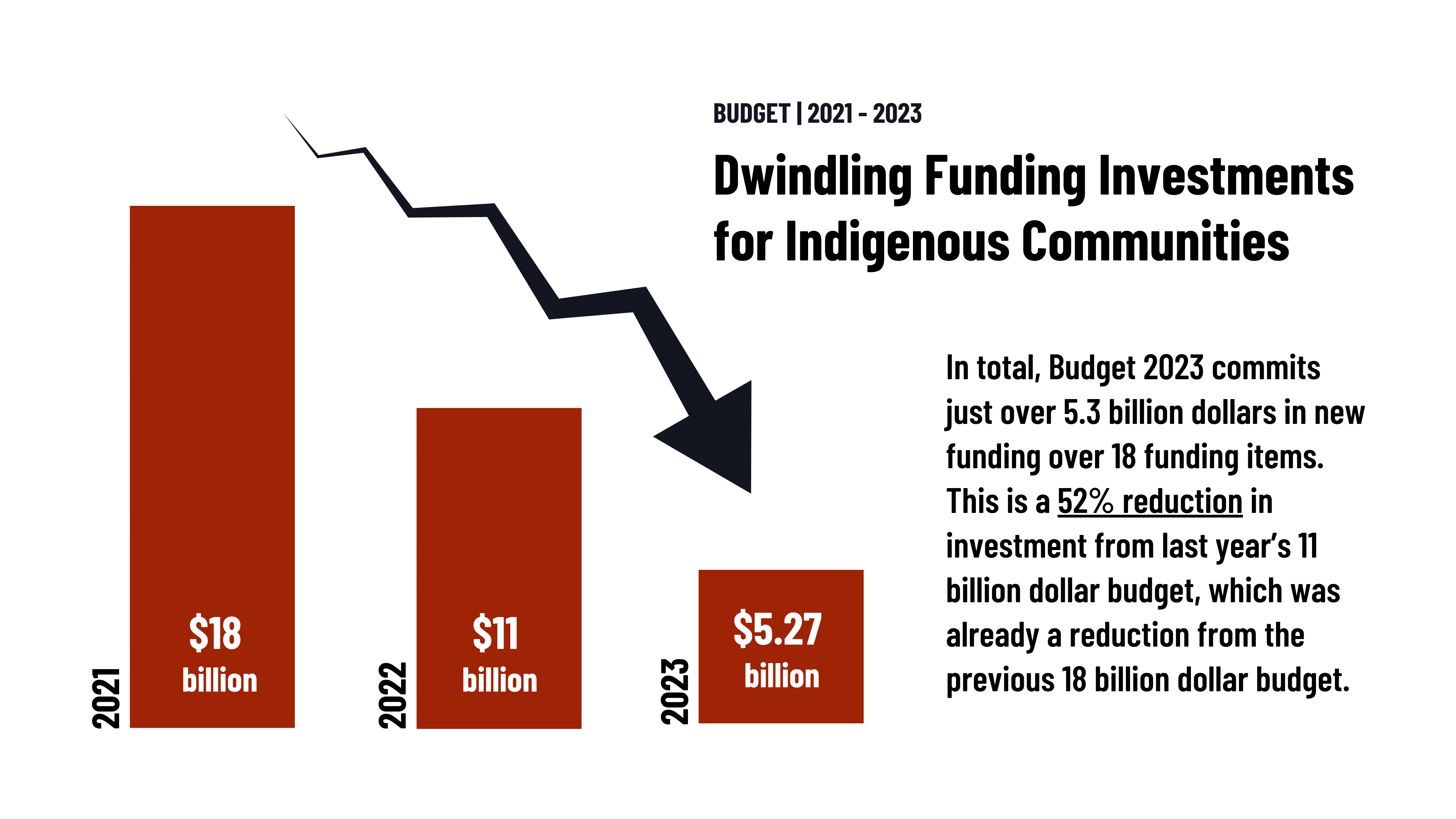

In total, Budget 2023 commits just over $5.27 billion in new funding over 17 funding items. This is a 52% reduction in investment from last year’s $11 billion budget, which was already a reduction from the previous $18 billion budget.1

In other words, we are seeing a trend in reduced spending, year over year.

While there are another $5.24 billion allocated towards Indigenous people in this budget, it was money already announced2, outlined in the Fall Economic Statement3, or was court mandated in a settlement agreement.4

Further, about $3.56 billion worth of other funding mentions Indigenous people as one of the intended beneficiaries, among several others. Still, it outlines no minimum amount that must be allocated our way. Even if we add these amounts to the new funding, we are still short of the commitments made in Budget 2021.

Following the Money: Whose Priorities?

As Trudeau’s Liberals try to prove that they are “fiscally responsible” following three-or-so years of relatively high spending at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is disappointing, but not surprising, that Indigenous people saw the rate of investment into their priorities slashed.

To see where the funding is and is not directed, I examined the three major Indigenous advocacy bodies’ — the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Métis National Council (MNC), and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) — pre-budget submissions and their corresponding priorities (while these organizations are not necessarily perfect representatives of all Indigenous peoples and their needs, they help give a sense of the scope and scale of immediate changes being demanded for comparison).

Housing

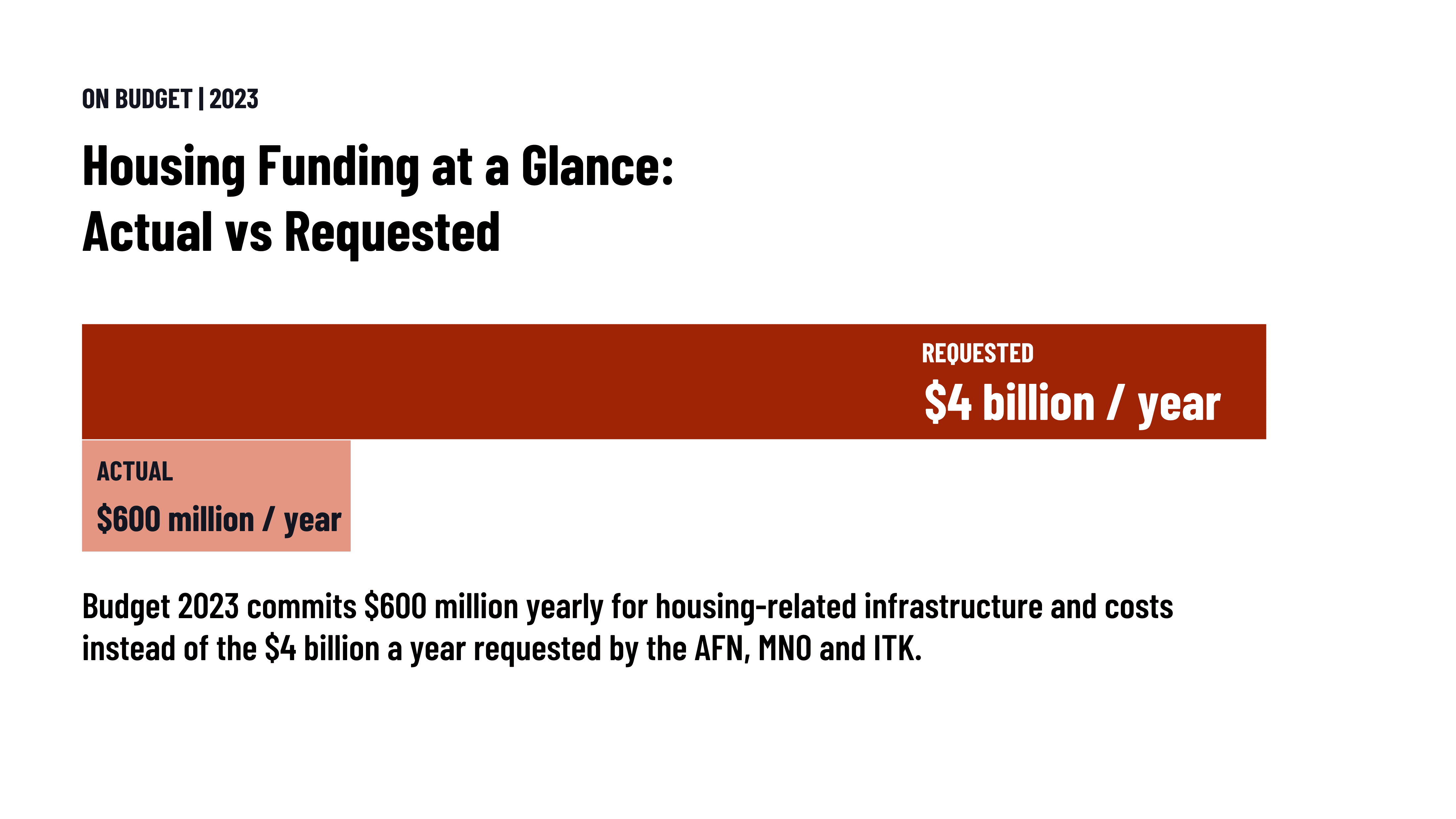

Looking closer at that total $5.3 billion amount, we see that most of it ($4 billion) is allocated towards implementing an off-reserve housing strategy, which is currently under development.5 So, how does the most significant Indigenous-specific investment in Budget 2023 compare to the demands of Indigenous organizations?

Looking at housing for First Nations alone, the AFN had requested $63.3 billion through to 2040 to bridge existing gaps and account for the growing population of First Nations communities6; the MNC requested $1.316 billion over six years7; and the ITK had been looking for $75 billion over 35 years for Inuit-specific infrastructure.8

Amalgamated and then broken down into yearly sums, the Indigenous organizations asked for $139.6 billion spread over the next few decades — or about $4 billion annually. By contrast, Budget 2023 committed only $600 million yearly for only seven years. In short, this year’s commitments nowhere near meet Indigenous people’s needs when it comes to housing.

Health

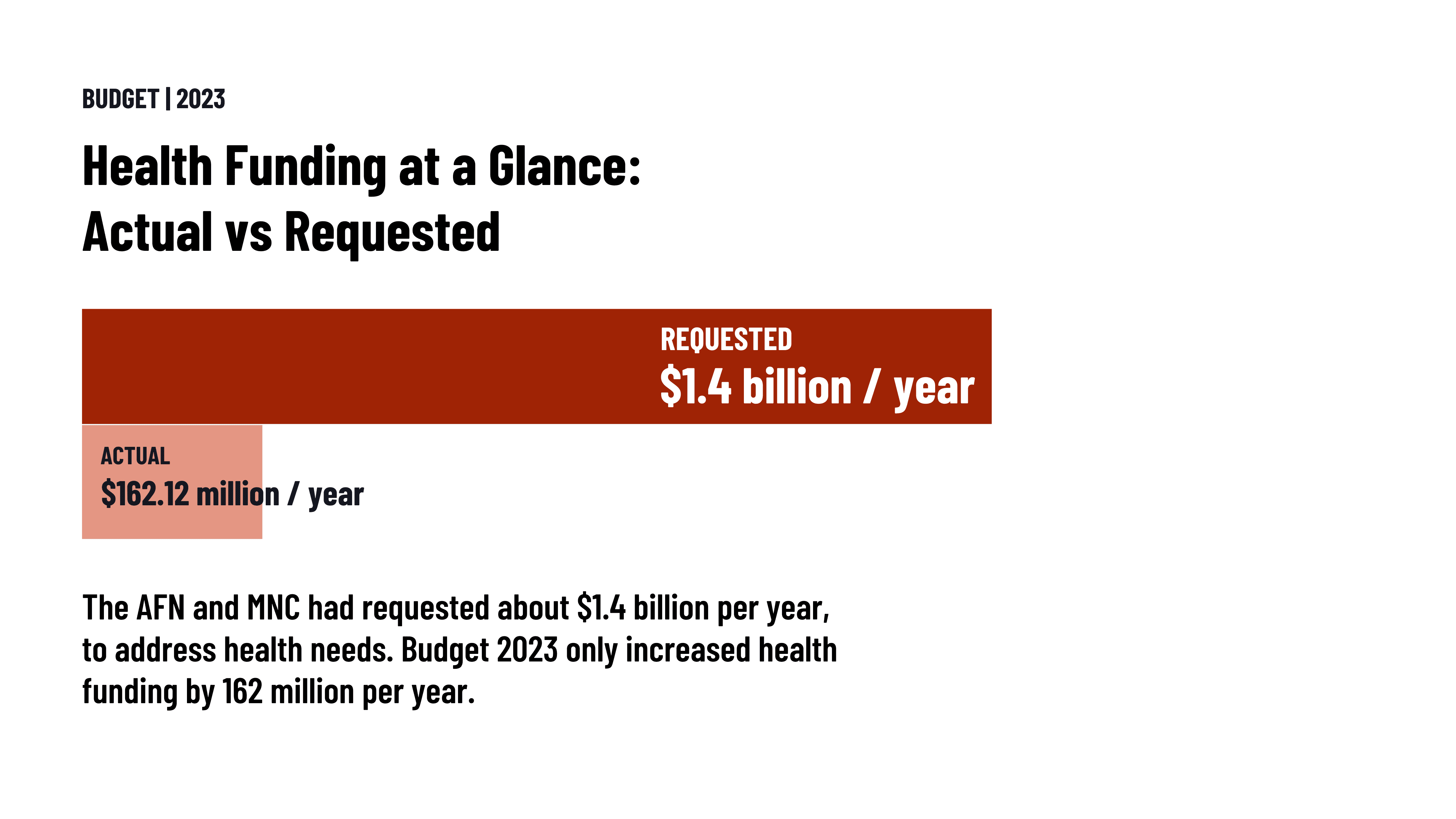

The second single largest policy area covered in this budget was health. Here, Canada reiterated its earlier-made commitment to $2 billion over ten years to the Indigenous Health Equity Fund9 and added $810.6 million over five years to upkeep Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) for status First Nations and support medical travel.10

Comparatively, the AFN and MNC had requested $6.84 billion over five years, or about $1.4 billion per year, to address health needs.11 Again, we see mere fractions of what is needed being allocated.

Further, most of the funding is in areas not prioritized by the AFN and MNC. While these two bodies took care to specify how their requested money should be directed, neither included health travel or NIHB.

The only budget allocation that responds to a specified area of healthcare outlined by an Indigenous leadership body is related to tuberculosis among Inuit. Canada committed $16.2 million over five years here, whereas the ITK requested $18.8 million yearly for seven years — a $115.4 million shortfall.

Land, Economics, and Self-Determination

Nearly all the remaining budgetary items fall under the umbrella of land, economics, and self-determination — commitments totalling $111.4 million of this year’s spending.

In this section, while ignoring the land and governance-specific asks of the three major Indigenous advocacy bodies, Canada has emphasized its intention to pursue “economic reconciliation.” This is premised on the assumption of “unlocking the potential of First Nations lands.”12

While a new economic relationship is undoubtedly necessary, why is it dependent on opening up First Nations’ territories to extraction? It’s far from the only option — the Yellowhead Institute’s 2021 Red Paper, Cash Back, for example, outlines ten different ways to develop transformative economic models that don’t require integration into or reliance on global capitalism.13

Indigenous people have a right to determine the use and benefits related to resources on their lands, certainly. But they also have a right to pursue non-exploitative modes of economic development and should be provided with the means to do so. Unfortunately, this latter right is not one prioritized by Budget 2023.

Budget Analysis

While there is a clear difference of opinion between the federal government and the National Indigenous Organizations on what is required to “close the gaps,” there are also some trends that are emerging in how the federal government is allocating resources. These trends can tell communities much about Canada’s general approach to Indigenous relations.

Consultations Galore

One of the most striking patterns from this budget is repeated investment in a particular type of action: consultations. More specifically, considerable funding (about $52.4 million) is spent on consultations, creating frameworks or advisory tables, and appointing individuals to advise on future action.

Some funding is even dedicated to facilitating consultations about how Canada can consult!14

Plans of action are necessary and cost money to do well. Still, it is hard to avoid frustration when Canada — especially since 2015 — has nearly consulted Indigenous people to death. We have so little time to do anything other than consult. Yet, as the priorities discussion above highlights, we aren’t listened to in the end, anyway.

Between the Penner Report, RCAP, the TRC, the MMIWG Inquiry, and countless other inquiries, investigations, and commissions, Canada has mountains of evidence telling them precisely what changes they need to be making with immediacy. These changes rarely occur, and if they do, it is even rarer that they would meaningfully disrupt the settler-colonial status quo.

It is a failure to act boldly and responsively, ensuring that Indigenous people remain stuck on a multi-million dollar hamster wheel, being asked to co-develop plans they are told will eventually lead to a change that never comes in full.

Trickle-Down Reconciliation

Finally, half the new funding points are allocated to CIRNAC, National Resources Canada, and/or the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency.

Only one item mentions specific First Nations (Peguis First Nation in Manitoba and Louis Bull Tribe First Nation in Alberta to exercise jurisdiction over their child welfare systems15). Two more are allocated to groups led by Indigenous people through bodies associated with the MMIWG Inquiry.16

While it is true that these branches of the federal government have substantial capacity to distribute this funding, there have long been calls to move away from the Canadian government filtering money — often through onerous and capacity-sucking proposal processes — through various departments. Even as we have these investments, Indigenous people are nonetheless still expected to come hat-in-hand to the relevant budget masters.

The 1983 Penner Report, for example, “advocated for a “radically different approach to its fiscal arrangements” for Canada with First Nations: it recommended that Canada send fiscal transfers to First Nations, as it did to provinces, and phase out Indian Affairs and middle people.”17 (This would accompany a legislative transition recognizing self-government and prioritizing self-determination).

In the 40 years since this report was released, we have not seen such a transformation toward economic self-determination. This fiscal year, we will not know that change either.

How Far Away are we from a “Good” Budget?

This year’s analysis shows that the Federal Government has failed at every turn to meet the four elements of a “good budget” outlined at the outset of this Brief.

So long as Indigenous people continue to be insufficiently invested in, Canada cannot posture as interested in a new economic relationship. As much as we may be conditioned to do otherwise, Indigenous people will not be grateful for budget scraps.

Citation: Yesno, Riley. “Budget 2023: A Profound Failure to Meet Indigenous Demands” Yellowhead Institute. 6 April 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2023/04/06/budget-2023/

Endnotes

1 Riley Yesno, Balancing the Budget at Indigenous Peoples Expense (Toronto: Yellowhead Institute, 2022), para 7.

2 Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau, Working in partnership to deliver high-quality healthcare to Indigenous people, (Vancouver, B.C.: Government of Canada, 2023).

3 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, (Ottawa: Department of Finance Canada, 2023), 131.

4 Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Settlement agreement reached for Gottfriedson Band class,” Newswire, Jan. 21, 2023.

5 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 46.

6 Assembly of First Nations, Written Submission for the Pre-Budget Consultations in Advance of the Upcoming Federal Budget 2023, (Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations, 2022), 4.

7 Métis Nation Council, Building Capacity to Deliver for our Citizens Federal Budget Submission for 2023, (Ottawa: Métis Nation Council, 2023), 14.

8 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Pre-Budget Submission 2023, (Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2022), 1.

9 Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau, Working in partnership to deliver high-quality healthcare for Indigenous peoples.

10 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 129.

11 Assembly of First Nations, Written Submission for the Pre-Budget Consultations, 2; Métis Nation Council, Federal Budget Submission for 2023, 18.

12 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 128.

13 Naiomi W Metallic and Shiri Pasternak, Cash Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper, (Toronto: Yellowhead Institute, 2021), 51-65.

14 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 93.

15 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 131.

16 Government of Canada, Budget 2023, 130.

17 Metallic and Pasternak, Cash Back, 37.