- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

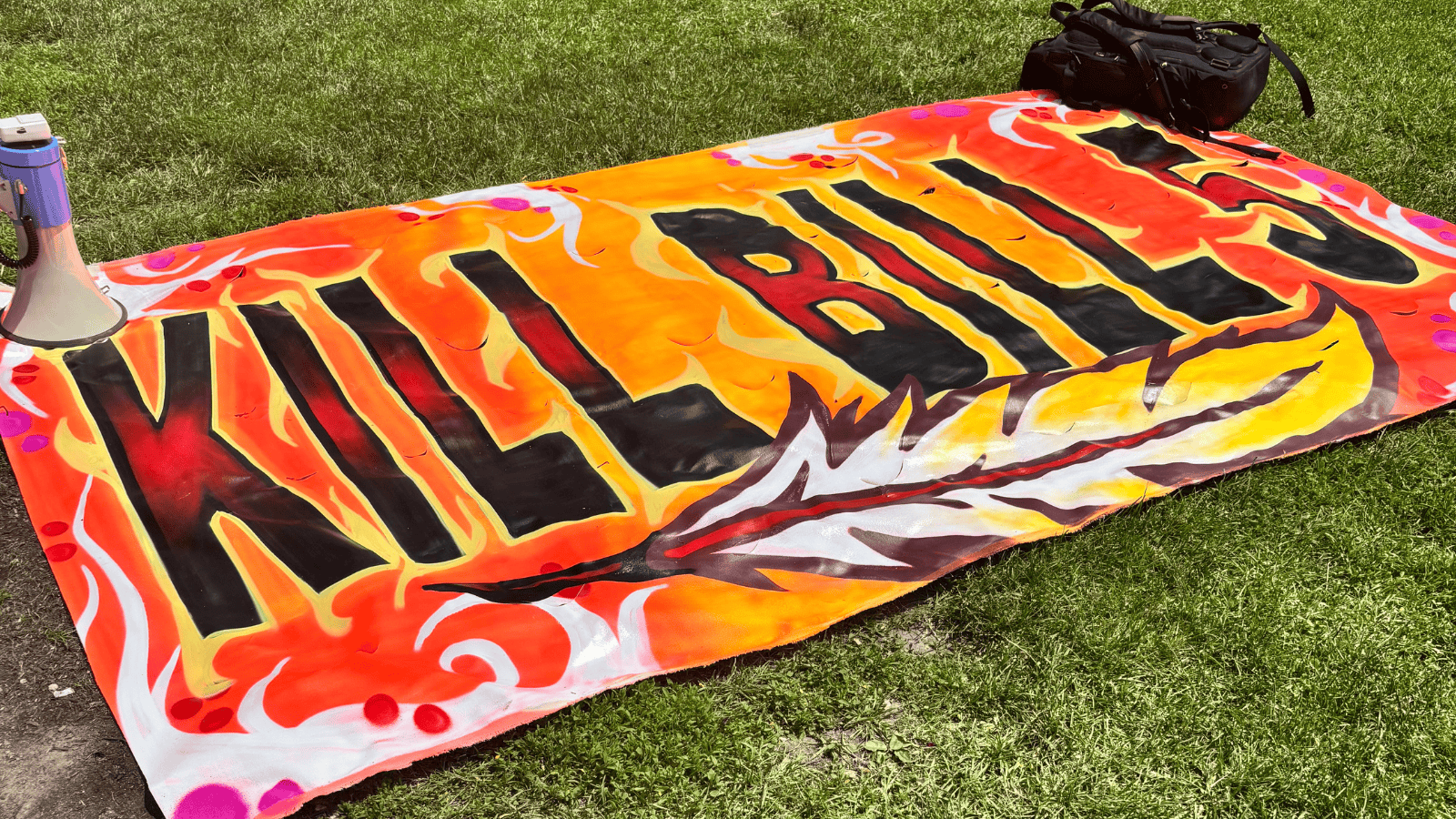

Earlier this week, Indigenous people from across Ontario came to the steps of the Ontario legislature to challenge the Provincial Government’s Bill 5, Protect Ontario by Unleashing our Economy Act. Many Northern First Nation leaders testified at committee meetings on the Bill. Meanwhile, during a Parliamentary debate, NDP MPP Sol Mamakwa was removed from the Legislature after the Speaker ruled that his remarks – criticizing the legislation and accusing the Government of lying to First Nations about respecting their rights – went too far.

What Is So Contentious About Bill 5?

The 230-page omnibus legislation repeals or suspends sections of numerous existing Ontario laws and introduces new laws, with the goal of promoting economic development. Against the backdrop of an unpredictable economic climate, driven primarily by U.S. tariffs and related nonsense, Ontario’s government believes that its own regulations delay development. So, in an effort to remove the “leash”, they plan to create “Special Economic Zones” – bubbles of industrial activity free of environmental assessment requirements, including archaeological assessments, species at risk provisions, and elements of the provincial Planning Act.

The land, animals, ancestors – all potentially sacrificed – to get minerals out of the ground and to market.

Indigenous people know this approach as the overarching philosophy of the country for the past 150-200 years. But the gains resulting from Indigenous resistance over that same period of time have forced restraint. Constitutional principles like the Duty to Consult, for example, now require deliberation and a balancing of resource extraction with Indigenous rights. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. But Bill 5 turns back the clock.

Indigenous communities are right to be concerned.

Included in the legislation is a pre-exemption from environmental assessment for the Eagle’s Nest Mine. While Ontario suggests the project doesn’t really need an environmental assessment, the law formally excludes the project from that process. This despite it being a multi-mineral mine in the Ring of Fire, aiming to produce nickel, copper and potentially chromite, from 300,000 tonnes of underground mining material annually for the next 20 years. Eagle’s Nest will be the first of many exemptions, no doubt.

So, what happens to the Duty to Consult in cases like these?

The End of Consultation?

The Duty to Consult in Ontario (and many other jurisdictions) is triggered by the environmental assessment process. Does this mean that when there is no assessment, there is no consultation? Probably not. But it isn’t entirely clear. Ontario has not clarified when and how consultation will unfold in Special Economic Zones – but they have delegated the consultation process to “trusted proponents” (undefined in the legislation). In other words, the company undertaking the development will now manage the consultation and accommodation themselves. While this has been an emerging practice in Canada – and the law allows for this to a degree – it can lead to disaster and the Supreme Court has consistently affirmed that the “legal responsibility” lies with the Crown, not companies (though it’s increasingly harder to tell the difference).

Put in more straightforward terms, this legislation further obscures the process and requirements for consultation and then outsources it to Industry to administer.

First Nation leadership isn’t interested. Invoking Treaty rights and the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, Chiefs Alvin Fiddler, Shelly Moore-Frappier, Leo Friday, Linda Debassige, among others, insist on the concept of consent. Absent that, “there will be conflict on the ground” and/or these projects will “stall and get tied up in court.” I suspect most legal experts in the country would agree with them.

The Indigenous Rights / Title Fight

In some ways Ontario is a test for the rest of the country. Ford is not the only Premier using Trump as an alibi to cover the calls for fast-tracking development. During the Federal Election campaign Mark Carney made arguments for “economic corridors” and accelerated regulatory approvals for resource development. In this vision, Indigenous communities happily subscribe because they, so the argument goes, will benefit from those developments.

There is no doubt that some First Nations want to participate in resource development, to varying degrees. But the approach being taken in Ontario, and Canada more generally, will not be accepted. Treaty rights, consultation and/or consent are not discretionary. They are foundation of a mutually respectful relationship.

Moreover, the economic crumbs of resource extraction projects on offer are not incentives. They are insulting, considering those resources belong to First Nations.

Finally, “unleashing” economic development by suspending environmental protections is less than desirable against the backdrop of a climate crisis.

The slogan “elbows up” has been deployed by Canadian politicians to prepare for the fight with American economic interests. But they have a preliminary bout first; one against an underestimated but veteran opponent that hasn’t dropped their elbows in a few hundred years. For Ontario (and Canada) to avoid it, there must be a deliberate turn toward negotiating a different kind of land and resource regime.

King, Hayden. “The Elbows are Up: Ontario’s “Special Economic Zones” and Indigenous Rights,” Yellowhead Institute. 05 June 2025. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2025/06/05/the-elbows-are-up-ontarios-special-economic-zones-and-indigenous-rights/

Photo by Kelsi-Leigh Balaban