IN MAY 2020, the Abolition Convergence had planned to host a pre-conference to the Native American Indigenous Studies Association gathering in Toronto called Imagining and Decolonizing Abolitionist Futures. It was canceled when the pandemic hit, but the work continued.

Our organizing committee is a collaboration of artists, activists, academics, and people with direct experience with the carceral system. Our group includes Indigenous people, Black people, people of colour, white people, queer/trans* and 2-spirit people, younger and older people, people who have been incarcerated and people who have worked and struggled against incarceration, detention, deportation, and settler colonialism in various ways.

We got together to provide this guide for Prisoners Justice Day, keeping in mind the metaphor of our conference was mushrooms playing a restorative role in rebuilding all the root systems that have been damaged.

On August 10, 1975, the first Prisoners’ Justice Day (PJD) took place at Millhaven Penitentiary in Bath, Ontario, in commemoration of Eddie Nalon, who took his own life one year earlier while incarcerated.

Every year since, prisoners throughout so-called Canada (as well as internationally) have engaged in day-long fasts and labour strikes to call attention to the lethal effects of the prison system and to honour those who have died. PJD provides us with an opportunity to reflect upon and act in resistance to the inherent violence of prisons and the penal apparatus (i.e., police, social workers, etc.), and to interrogate the colonial logics of containment and control that underpin this apparatus.

In settler states such as Canada, the justice system is an integral component of settler colonial warfare against Indigenous peoples. As the sources in this reading guide make clear, the criminalization, segregation and containment of Indigenous peoples is a deep-seated, ongoing process designed to remove Indigenous peoples from their lands, communities, families, laws, cultures, and languages. Prisons are a colonial imposition on Indigenous lands.

As Ojibwe Elder Art Solomon explains, “We were not perfect, but we had no jails… no old peoples’ homes, no children’s aid societies, we had no crisis centres. We had a philosophy of life based on The Creator, and we had our humanity.” An abolitionist future, then, must center the stories of this land as essential to collective flourishing and care.

As of late, there has been increased public consciousness around penal abolition and an exciting turn toward the possibility of a world without prisons. We have seen the release of many useful reading lists and guides that provide a sense of the rich history of abolitionist theory and organizing, particularly as informed by the work of Black feminists. An Indigenous Abolitionist Study Guide adds to this corpus, gathering together the work of Indigenous organizers and scholars, and addressing the need for an explicitly Indigenous, anti-colonial abolitionist analysis of the penal system.

Such an analysis illustrates the necessity of defunding and dismantling the punitive, carceral structures characteristic of settler colonial society, and turning, instead, to Indigenous Knowledges as a guide to how to create and sustain good relations with each other.

Where are we and what are the governing systems and principles that place us all in networks of kinship, partnership, and treaty relations across these lands?

In the country currently known as Canada, there are hundreds of Indigenous nations with political, legal, social, cultural and economic systems that emerged in relation to every place we lived. It is impossible to summarize thousands of years of legal history across so many nations, over such a vast country, in one set of readings. But here are some histories, laws, and philosophies that breathe life into the present.

RELATED RESOURCES

Vanessa Watts, “Indigenous place-thought & agency amongst humans and non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!).” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 2, No. 1, 2013, pp. 20-34 2013

Leanne Simpson, “Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa: Precolonial Nishnaabeg Diplomatic and Treaty Relationships,” Wicazo Sa Review, Volume 23, Number 2, Fall 2008, pp. 29-42

Ǧviḷásdṃalas Haíɫzaqv: Building Our Constitution

Jeremy Dutcher, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa

When colonizers came to these lands, they may have marked new countries on the map but that didn’t mean they could control the territory.

It would take a great deal of force, compounded by new diseases that decimated Indigenous communities, for settlers to occupy native homelands. A key strategy for stealing these lands was the denial of Indigenous law and the imposition of settler law as the singular and absolute set of rules, as well as introducing new forms of punishment and justice.

This set of sources take different historical viewpoints of this transition: they reveal how the continent was once governed by a multitude of Indigenous legal systems; then a plurality of Indigenous and settler laws overlapped in both consensual and violent ways; finally, settler law was self-declared as the only acceptable system of justice, connected to the property claims of the new settler colonial states. In this final phase, the criminalization of Indigenous peoples began in earnest.

RELATED RESOURCES

Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark. “Criminal Empire: The Making of the Savage in a Lawless Land.” Theory & Event Vol. 19, Iss. 4, (2016).

Tasha Hubbard (Dir.), We Will Stand Up: History Animation, 2019

Alex Williams (Dir.), The Pass System, (Doc film, 50 Mins), 2015

Rustbelt Abolition Radio Talks With Nick Estes, Who Talks About The History of Incarceration and its Relation to Native Genocide And Colonization

Arthur Manuel, “In Canada, white supremacy is the law of the land.” Now Magazine, Oct. 26, 2017

Though there are many important similarities and shared histories between the colonization of Indigenous peoples who were contained in what became known as the United States and Canada, there are also important differences.

One key difference is the RCMP. The national police force in Canada was raised to subjugate Indigenous peoples in what became the prairie provinces. The North West Mounted Police [NWMP] became the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but the NWMP’s first mission was to attack the nations refusing treaty and surrender of their lands. The RCMP subsequently played key roles in the incarceration of First Nations on reserves, abducting children into residential schools and arresting the parents of those who refused, breaking up Indigenous ceremonies, slaughtering Inuit sled dogs, and other violent disruptions. Today, national, provincial, and local municipal police forces continue to terrorize Indigenous peoples through surveillance, arrest, murder, and sexual violence.

RELATED RESOURCES

M. Goldhawke, “A Condensed History of Canada’s Colonial Cops: How the RCMP has secured the imperialist power of the north.” The New Inquiry. March 10, 2020

Tasha Hubbard (Dir.), Two Worlds Colliding, 2004

Alanis Obomsawin (Dir.), 270 years of resistance, 1993

Pam Palmater (2016). Shining light on the dark places: Addressing police racism and sexualized violence against indigenous women and girls in the national inquiry. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, 28(2), 253-284

Emily Riddle, Abolish the Police: The Financial Cost of Law Enforcement in Prairie Cities, June 27, 2020

Patrica Monture-Angus, the late and fierce Mohawk lawyer, described the relationship between the child welfare system and the prison system in Canada as a “vicious cycle.” In Thunder in My Soul, she writes:

I am deliberately connecting child “welfare” law with the criminal “justice” system… The child welfare system feeds the youth and adult correctional systems. Both institutions remove citizens from their communities, which has a devastating effect on the cultural and spiritual growth of the individual. It also damages the traditional social structures of family and community. Both the child welfare system and the criminal justice system are exercised through the use of punishment, force and coercion (194).

She also notes that family breakdown is known by criminologists to be at the core of “criminality” – yet the historical failure of the system to recognize First Nations people and children as subject to pressures of assimilation and dispossession remains in place, despite high levels of incarceration and in spite of which children continue to be removed.

Colonial incarceration is also a place of containment for Indigenous land protectors. The violent removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands continues to be an active form of colonization in Canada, not just a relic of the past. Criminalization of land defenders happens both within and outside of settler law – it is a by-any-means-necessary type of violence that is supported by structures of white supremacy – an investment in the status quo of capitalism and colonialism and a twisted economic system premised on racial hierarchy, gender-based violence, dispossession, and massive wealth theft.

RELATED RESOURCES

Part 1

Colonial Incarceration in Canada: A Yellowhead Institute infographic

Vicki Chartrand, “Unsettled Times: Indigenous Incarceration and the Links between Colonialism and the Penitentiary in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Volume 61:3 (July 2019): 67-89

Fran Sugar, “Entrenched Social Catastrophe: Native Women in Prison,” Canadian Woman Studies Vol 10, 2/3, 87-89

Indigenous Knowledge and Abolition: Criminalization, Decolonization and Lessons from Indigenous Justice Systems with Pamela Palmater, Giselle Dias, Joey “Twins” Young, Wanda Whitebird, Les Harper, hosted by Nicole Penak

Part 2

The Red Nation Podcast with Little Feather and Leoyla Cowboy on DAPL political prisoners

APTN News, Land defender Kanahus Manuel arrested using excessive force says lawyer | APTN News

Audio recording of Wolverine, Williams Jones Ignace, interviewed by Greg Macdougall in Waterloo ON, 2002 about the Ts’peten (Gustafsen Lake) armed standoff with RCMP; text of the December 2015 open letter from Wolverine to Canada’s Prime Minister and Minister of Justice calling for a public inquiry to address what happened around Gustafsen Lake.

The worlding of Abolitionist futures is both an imaginative and physical praxis. We want to get to a place where theory work – a commitment to understanding how carceral systems spread and operate in our society – meets ways of being in relation.

When challenging carceral systems, inevitably we are posed with the questions: so, what are your alternatives? Who will take on these roles? What systems could possibly replace prisons or the police? Even more inevitable, the “social worker” will be offered up as an alternative. The social worker role is something easy to grab onto, a ready-to-serve option. The reasons why social work is so easy to reach for is deeply rooted and entangled in settler colonial narratives of white supremacy, superiority, benevolence, and salvation.

It is also pragmatic: the same systems of settler colonialism have been so successful in violently dismantling relationships have also extracted the individual from Indigenous collective kinship, preferencing “nuclear family” units which further isolates Indigenous peoples from each other, from their lands and their ways of sustaining life.

Much of the scholarship begins implicating social work post-Confederation, focusing on social work’s involvement in residential schools and the successor to this system, child welfare. But do not let this context frame social work as a brief historical diversion from otherwise noble original intentions. Much has been documented about Indigenous societies and the role of social work in the exercise of removing and replacing these structures with European peoples, communities, and practices. Scholars have worked to articulate both this historical and present relationship to ongoing settler colonialism, and yet we need only turn to Indigenous families and communities to see the multigenerational violence levied by this system.

It is our work here to understand how social work has always been and is today, not separate from, or an alternative to carceral systems, but an explicit element or technology of the carceral society peddled by settler colonialism.

This professionalization and formalization of care plays an important and insidious role in sustaining the carceral state itself. We must interrogate the social work narrative of providing care where gaps in relationships exist, to understanding how it works both overtly and covertly to erode and sustain our isolation in order for us to restore the relationships and ways of being with one another that these “systems of care” have sought to make unimaginable.

RELATED RESOURCES

“Coming home: Raven Sinclair and the Sixties Scoop,” Discourse Magazine, University of Regina

Connie Walker (Host & Writer), CBC Radio’s Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo

Hart, M. A. (2003). Am I A Modern Day Missionary? Reflections of a Cree Social Worker. Native Social Work Journal 5

Craig Fortier, & Ed Hon-Sing Wong, (2018). The settler colonialism of social work and the social work of settler colonialism. Settler Colonial Studies, 1-20

There is no question that in community organizing spaces across this country, the leadership of women, Two-Spirit and Trans people shines a bright beacon of light into the future.

Leanne Simpson writes that “a critical interrogation of heteropatriarchy must be at the core of nation building, sovereignty and social change.” She writes, “I would argue that this requires a decolonization of our conceptualization of gender as a starting point.” (Dancing on our Turtle’s Back, 60).

Alex Wilson (Neyonawak Inniniwak from the Opaskwayak Cree Nation) writes about Two Spirit identity as part of this fundamental resurgence. She writes: “Two-spirit identity is one way in which balance is being restored to our communities.” It returns an acceptance of a demonized culture: “Penalized and punished for our acceptance of gender and sexual variance, many of us learned that the most certain way to survive was to take these teachings underground, out of sight of the colonizers.” Whereas, “coming in is an act of returning, fully present in our selves, to resume our place as a valued part of our families, cultures, communities, and lands, in connection with all our relations” (Our Coming In Stories: Cree Identity, Body Sovereignty and Gender Self-Determination, Journal of Global Indigeneity 1.1 2015). She clearly links the struggle for land with gender justice: “Indigenous sovereignty over our lands is inseparable from sovereignty over our bodies, sexuality and gender self-expression. This is at the root of the very contemporary understanding of identity held by many two-spirit youth today.”

RELATED RESOURCES

Sarah Hunt, In her name – relationships as law: Sarah Hunt at TEDxVictoria, 2013

jaye simpson, “A Conversation I Can’t Yet Have: Why I Will Not Name My Indigenous Abusers,” GUTS Magazine, 2019

The Red Nation Podcast – Unis’tot’en Camp: no access without consent w/ Anne Spice

Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, Violence on the Land, Violence on our Bodies: Building an Indigenous Response to Environmental Violence

Carol Martin and Harsha Walia, Red Women Rising: Indigenous Women Survivors in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre, 2019

This reading list could be a million miles long. Here is a small sample of inspiration.

RELATED RESOURCES

Hewitt, J. G. (2016). Indigenous Restorative Justice: Approaches, Meaning & Possibility. University of New Brunswick Law Journal, 67, 313

Wahkohtowin Justice Map: Justice and Injustice in Saskatoon

Amanda Strong (Animator / Director) Biidaaban (The Dawn Comes), based on the stories of Leanne Simpson

Sefanit Habtom and Megan Scribe, “Together: Co-Conspirators For Decolonial Futures,” Yellowhead Institute, June 2, 2020

Citation: Toronto Abolition Convergence. “An Indigenous Abolitionist Study Guide.” Yellowhead Institute, 10 Aug. 2020, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/08/10/an-indigenous-abolitionist-study-group-guide/

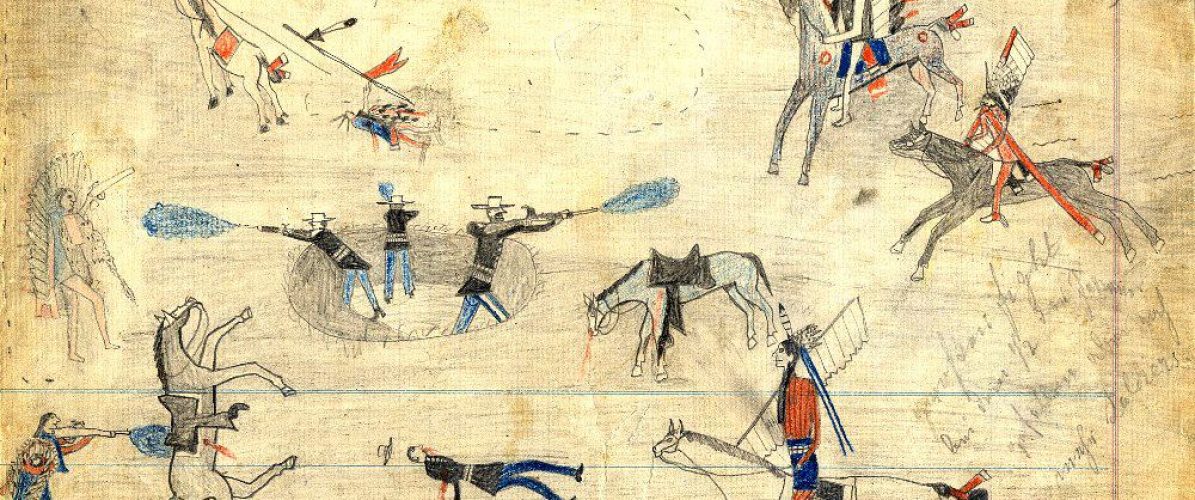

Feature Image: Drawn in Fort Marion, this is one of the famous and beautiful “ledger drawings” created by captured Cheyenne and Kiowa prisoners of war in the late nineteenth century. Click here for more information.