- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

BLACK ARTISTIC CREATION has always been vital to Black survival.

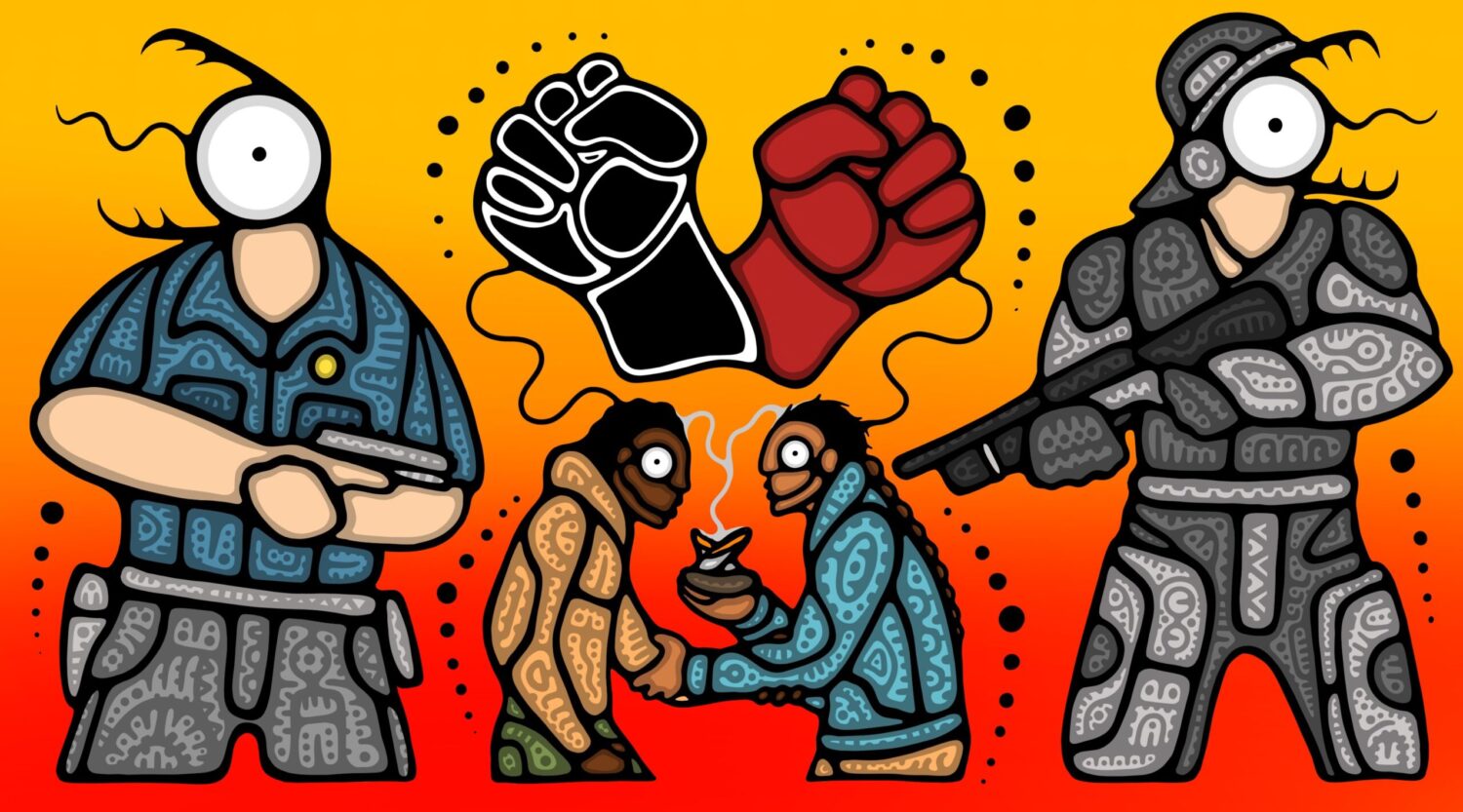

So in this moment of rupture—of deep anguish but also hope for a future free of the violent colonial and capitalist state apparatuses that target Indigenous, Black, and Black-Indigenous people for exploitation and death—I turn to Black art for nurturance, and vital teachings about the right way forward.

Writing by visionary author Wayde Compton offers an imagination that is especially vital now. His speculative short story collection The Outer Harbour (2015) opens up pathways for imagining an alternate future world born of the strength of solidarity between Black and Indigenous people.

by Tsista Kennedy

The Theft of Life, Labour & Land

At the centre of Compton’s short story collection is a thought experiment: what social relations would be made possible if a brand new land mass were to suddenly emerge out of the Salish sea, off the west coast of Turtle Island, what settlers call “British Columbia”? In the story “The Lost Island,” we meet Fletcher, a Snohomish-Salish activist, and his Black girlfriend, Jean, who organize an anti-colonial action to claim the unpopulated Island which has been designated a “protected zone, a national site for research” and which is off-limits to everyone but scientists (34). Fletcher understands the island as “Indian land” (34) and his decision to row out to the island in a Zodiac to claim it as “Unceded Native Land” is intended to “Throw a monkey wrench in the data collection. Get in on the anti-colonial ground floor, like” (34). At the beginning of the story, Jean is uncertain about her role in the group and their planned action. “I’m not Native, Jean says, planting her non-sequitur in the air […] I don’t know if I should be here, she says. I mean, I figure I should say that right now. Should I be here?” (35).

The grammar of Jean’s “non-sequitur” echoes the violent historical processes, beginning in the sixteenth century, that forcibly removed Africans from their lands and abruptly planted them in lands expropriated from Indigenous peoples’ nations. As a “displanted” Black person, Jean shares with Fletcher an ancestral history of dispossession, racial subjugation, and state violence. But she is careful to not collapse the difference of her Blackness into his Indigeneity.

While the colonial processes that expropriate lands from Indigenous people and target them for genocide, and the capitalist processes that steal the life and labour of Black people are twinned and overlapping forces, they are not the same.

As Jean acknowledges, the histories, identities and cultures of Black and Indigenous people, and their relationship to the land, are not identical nor are they reducible to one another.

New/Old Political Imaginations

It is our differing histories regarding land in particular that has given rise to friction in our relationship with each another as Black and Indigenous people. The Black emancipation project on Turtle Island has—until now—been largely predicated on fighting for inclusion and belonging in a colonial state apparatus on land that, in poet NourbeSe Philip’s words, remains “unfree.”

“For Africans in the Caribbean and the Americas,” she writes, “who in the words of the spiritual, have been trying to sing their songs in a strange land, be/longing is a problematic. Be/longing anywhere—the Caribbean, Canada, the United States, even Africa. The land, the place that was the New World was nothing but a source of anguish—how could they—we—begin to love the land, which is the first step in be/longing, when even the land was unfree?” (48-9).

Compton’s short story offers a different vision for Black liberation, one that depends not on assimilation into the colonial state apparatus but rather on the affirmation of Indigenous political sovereignty.

Compton writes that “For Jean there is within this crazy plan” to row out to the island in a Zodiac, “a kind of retort to the Vancouver she has known: the teacher, whom she loved, who one day out of nowhere called her a golliwog; all the where-are-you-froms and all the where-are-you-really-froms; being looked at or looked through, depending, but being summed up, appraised, pre-emptively estranged” (37). Jean’s commitment to the group’s land sovereignty action, then, is not posited on Black similitude with Indigeneity. She finds in her own Blackness—and in the history of the nation-state’s relentless betrayal of Black people—powerful reason for getting in a boat and rowing away from the shores of Canada, across the surface of the Salish Sea, toward a new political imagination.

Returning to Sacred Nations

Right now, across Turtle Island, #Black Lives Matter protesters are similarly revolting against the system of racist capitalism that “uses relationships, resources, laws and power to not only create divisions but to create groups of people that can be justifiably exploited” (Sharmeen Khan). The stability of the settler-nation state relies on keeping Black and Indigenous political interests divided. The recently published Toronto Star article, “Let’s save some outrage for treatment of Indigenous people,” written by the Star’s all-white editorial board and published at the height of the #BlackLivesMatter uprisings, is a perfect example of the ways white supremacy as a structure relies on dividing Black from Indigenous struggles.

The lost island of Compton’s story is imaginary. But the sacred nations in which Black people have been territorialized retain their vital political realities.

Each homeland of Indigenous nations has its own constitutional framework, political, legal and diplomatic structures, and economic systems that we can, in this moment of rupture, commit to affirming and upholding.

In this time of revolution, let us turn away, at last, from the shores of the colonial settler state which only betrays our citizenship, and turn toward fulfilling our citizenship responsibilities in the Indigenous nations in which we have arrived.

Endnotes

Compton, Wayde. The Outer Harbour: Stories. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2015.

Khan, Sharmeen (@colonizedmutant). June 18, 2020. Tweet.

Morgan, Anthony. “Black People are not Settlers.” Ricochet. March 12, 2019. https://ricochet.media/en/2538/black-people-in-canada-are-not-settlers.

Philip, NourbeSe. Bla_K: Essays and Interviews. Book*Hug, 2017.

Star Editorial Board. “Let’s save some outrage for treatment of Indigenous people.” The Toronto Star. June 12, 2020. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/editorials/2020/06/12/lets-save-some-outrage-for-treatment-of-indigenous-people.html

Citation: Vernon, Karina. “Black-Indigenous Futures in Art, Literature and #BlackLivesMatter.” Yellowhead Institute. July 7, 2020. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/07/07/black-indigenous-futures-art-literature-blm/