- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

AS OF JANUARY 26, 2021, there were 57 long-term drinking water advisories in 39 First Nations across Canada — 54 percent of these Bands have been under an advisory for longer than ten years. While water quality issues on reserves have long made headlines, the connection between water infrastructure and the outbreak of COVID-19 in First Nation communities is less known.

In a year-long investigation into water on First Nations, a consortium of university students and journalists led by the Institute for Investigative Journalism (IIJ), has found a correlation between COVID-19 outbreaks and cistern water systems. Our research reveals that outdated policies don’t fix modern problems.

CISTERNS are a type of water infrastructure that is often used in rural and remote locations, like reserves. They are large tanks located outside the homes that are filled weekly with treated potable water from the water treatment facility by delivery trucks. 15 percent of First Nation households rely on cisterns. Of those, many have expressed concern over the quality and quantity of water they are receiving.

Focusing on Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, the IIJ’s research revealed communities with cisterns experienced approximately twice the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks compared to communities with piped water systems.

While statisticians reviewed and verified the analysis, which was completed with the aid of ArcGIS technology, federal and provincial offices were unable to provide statistics or confirm the data. An in-depth study by academic researchers is called for in order to explore these preliminary findings and determine causes.

In other words, the water “crisis” was compounded by the pandemic, but it must be understood as a long-term health and safety issue that can no longer be put off for later. Later is here, now.

Cisterns aren’t the solution, but a link to the root problem

The water crisis for First Nation people living on reserves is a direct result of systemic racism embedded in Canadian colonial policy. It has led to complicated challenges that have proven difficult for communities and governments to solve.

Researchers have found that cisterns can be affected by multiple issues and sources of contamination, such as sources in the water delivery tanks, the cistern’s structural integrity, organic infiltration, rodents, and snakes. Cisterns and the water delivery truck can also be compromised if general maintenance is overlooked due to the high demand on the water delivery system.

Where the federal government has supported water infrastructure, it has tended to fund building or fixing water facility treatment plants, rather than providing basic infrastructure, like piped household water systems — instead, they build cisterns.

The reasoning behind this seems to be that the wide dispersal of homes makes piped water delivery costly; however, this reasoning ignores the fact that providing clean drinking water has long-term health and economic advantages, such as preventing the spread of infection, like a COVID-19 outbreak.

Covid and Cisterns

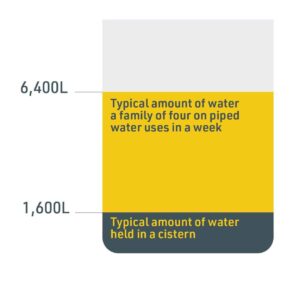

The IIJ has identified that COVID-19 outbreaks correlate with the usage of cistern water systems. Cisterns typically hold up to 1,600 litres of water — a quarter of what a family of four uses in a week when they have access to piped water. As such, households that rely on cisterns are forced to conserve water, which impedes their ability to follow public health guidelines that call for increased handwashing and household cleaning during an outbreak of an infectious disease.

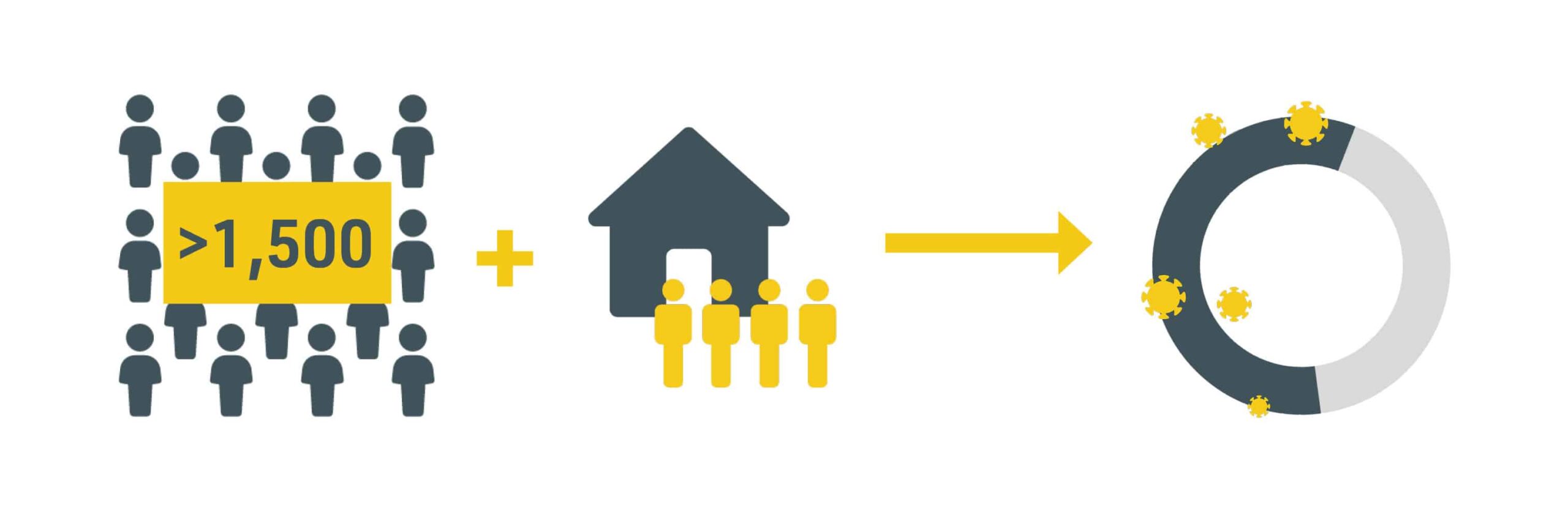

The IIJ’s data revealed that among First Nations in the four provinces with a population of less than 1,500 and a housing density of 3.5 to 4 people, more than half experienced an outbreak of COVID-19.

This data could point to several causes, one of which is overcrowding in housing. In 2016, a quarter of on-reserve First Nations lived in crowded housing. Moreover, one in five band members lives in a home in need of major repairs. Overcrowding exacerbates the shortage of water and makes it harder to conserve water and keep quarantine or self-isolation standards.

This data could point to several causes, one of which is overcrowding in housing. In 2016, a quarter of on-reserve First Nations lived in crowded housing. Moreover, one in five band members lives in a home in need of major repairs. Overcrowding exacerbates the shortage of water and makes it harder to conserve water and keep quarantine or self-isolation standards.

Water contamination has long-term effects on communities, even when systems are fixed. Due to historical water issues on reserves, there is still fear of contamination. As a result, most households get their drinking water from surrounding services. The IIJ notes this may mean multiple additional points of contact as a risk factor.

Broken Promises and an Auditor’s report

In 2015, Justin Trudeau committed to ending boil-water advisories on First Nations reserves within five years. He has not kept that promise and his deadline has now been extended past March 2021.

On February 25, 2021, Canada’s Auditor General released a report that revealed the federal government’s lack of commitment to resolving the long-term drinking water advisories on First Nation reserves. The report points out that it is unlikely that the March 2021 deadline will be met, forecasting that some long-term drinking water advisories will take years to resolve.

The main issues that constrain Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) are outdated policies and the inadequate funding formula for operation and maintenance of water infrastructure in First Nation communities. These are things for which ISC has responsibility, but refuses to provide adequate resources for.

The Auditor General’s report lists many funding shortfalls from the Federal government. A significant one is the funding formula for operations and maintenance that make it challenging, if not impossible, to retain the specially trained water system operators required for these systems. These trained professionals working on First Nations water systems are paid 30 percent less than their counterparts in off-reserve water treatment plants.

The Auditor General Confirmed What First Nations Already Knew

Pulling together the Auditor General’s report, the data collected, and interviews conducted, the IIJ found that the Federal Government was more focused on short-term fixes than long-term solutions. This is significant because interim fixes for smaller projects are prioritized, rather than finding the root problem to resolve the long-term drinking water advisories.

The Auditor General’s report was particularly damning when it looked into the impact of inadequate quality and quantity of safe water on First Nations’ ability to weather the global pandemic. It is clear that First Nations are more vulnerable to infection, severe illness and deaths from COVID-19 due to overcrowding and poor housing conditions, pre-existing health conditions, limited health care access and, significantly, lack of access to an adequate supply of safe, clean drinking water.

These are issues First Nations have been advocating to fix for decades that have fallen on unwilling ears.

The Water Crisis is a Racism and Colonialism Crisis

Water security for First Nations is the responsibility of the Federal government. In the Constitution Act, 1982 section 91(24) makes Canada legally responsible for “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians.”

It is important to make note of these powers because they reveal that the First Nations’ right to self-determination has been denied and the decisions made by the Federal government on their behalf do not support First Nations’ autonomy, well-being, or safety.

First Nations have endured at least 153 years of restrictive and paternalistic policies, with significant gaps that created social, environmental, and economic issues. The IIJ’s findings support calls for the Federal government to work collaboratively with First Nations to address these issues, especially when the severity of one long-standing crisis creates larger community issues such as a COVID-19 outbreak.

Endnotes

Research Credits

This brief draws on reporting by students and journalists at colleges, universities and media companies nationwide, including First Nations University of Canada, University of Regina, MacEwan University, Mount Royal University, APTN News, Global News, and Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

Researchers: Erica Endemann, Lila Maître, Karina Zapata, Noel Harper, Carol Eugene Park, Laurence Brisson Dubreuil, Angela Amato, Jaida Beaudin-Herney, Anukul Thakur

Data journalist: Emma Wilkie

Director: Patti Sonntag

Edited by: Shannon Avison, First Nations University of Canada; Shiri Pasternak, Yellowhead Institute; Damien Lee, Yellowhead Institute

Research advisors, Department of Mathematics & Statistics, Concordia University: Lisa Kakinami, Associate Professor; Arusharka Sen, Associate Professor

For tips on this story, please contact the reporters at: iij.tips(at)protonmail.com

See the full list of “Broken Promises” series credits and more information about the consortium here. Many thanks to Esri Canada, which donated licenses to its ArcGIS technology in support of the IIJ’s mission of providing quality information to underserved communities.

Citation: Beaudin, Jaida. “Water is Life: The fatal links between water infrastructure, COVID-19, and First Nations in Canada.” Yellowhead Institute, 09 March 2021, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2021/03/08/water-is-life-the-fatal-links-between-water-infrastructure-covid-19-and-first-nations-in-canada/

Feature Image: Seth Arcand