- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

The Anishinaabemowin phrase “nibi onje biimaadiiziiwin” or “water is life” has become a rallying cry for Indigenous environmental justice worldwide, addressing the ongoing threat of climate change and highlighting the multiscalar health, social, and environmental impacts of the extractive industrial occupation of Indigenous lands. However, even with such explicitly material roots as these, “water is life” has also been subject to co-option. For example, multinational corporations like Nestlé have cynically adopted the phrase to market their bottled water, all the while extracting millions of liters of water a day from Indigenous lands, contributing to extensive plastic waste, and then profiting off the water insecurity in Indigenous communities.

In their foundational article “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang draw attention to how struggles for decolonization are often co-opted and repurposed in ways that reinforce settler colonial power structures instead of challenging them. They remind us that “decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things…” (2012, 1).

The metaphorization of “water is life” resonantly depoliticizes and obscures the tangible stakes of water insecurity, bolstering settler-colonial power structures that render life unliveable.

Such metaphorizations represent battlegrounds for not only water security, but also the lives of Indigenous peoples. This brief presents compelling evidence surrounding the link between water insecurity and suicide in First Nations in Ontario, illustrating that “water is life” is not a metaphor, but is a struggle for life itself.

Suicide is a significant and long-standing issue affecting Indigenous communities in Ontario, as it is elsewhere in Canada. The disproportionate rates of death by suicide in our communities is widely documented to be approximately 3 times that of the national average (Kumar & Tjepkema, 2019), and represents a 50-year inequity and persistent colonial injustice (Ansloos & Peltier, 2022). The fact that so many of our communities live in a state of perpetual mourning is not inevitable but is reflective of the indignities of life under settler colonialism. Despite being framed primarily as a public health issue, research increasingly suggests that suicide in Indigenous communities is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple interlocking factors such as mental health, age, gender, socioeconomic status, historical and intergenerational trauma, and varied social and environmental determinants (Ansloos, 2018; Kumar & Tjepkema, 2019).

Water Insecurity & Mental Health

In recent years, a growing body of research has pointed towards water insecurity as a contributing factor to mental health and suicide in Indigenous communities (Boyd, 2011; Cunsolo Willox et al., 2013, 2013, 2015; Durkalec et al., 2015; Hanrahan et al., 2016; Redvers et al., 2015). This largely qualitative research indicates that First Nations communities with limited access to safe drinking water may experience disproportionately high suicide rates. Moreover, water insecurity may contribute to mental health challenges within these communities, which could potentially exacerbate suicide risk. Further, the impact of climate change has been found to affect mental health outcomes associated with suicide among Indigenous peoples across Canada. Exposure to unprecedented environmental change has been associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide ideation in some communities.

In others, water insecurity, the loss of traditional practices related to water use and management, and related stressors contributed to feelings of anxiety, depression, and a loss of cultural identity, which in turn may have ripple effects on suicidality.

In addition, environmental changes and associated damage to infrastructure resulting from climate change may be linked to increased psychosocial distress, which may in turn affect suicidality (Cunsolo Willox et al., 2013, 2013, 2015). For Indigenous peoples, these relationships are not surprising. Teachings like “nibi onje biimaadiiziiwin” inform us that water is life, and that our collective survival depends on being in good relationship with waterkin (McGregor, 2018; Todd, 2017). Where water violations occur, sickness and death are not far.

Such knowledge is particularly relevant in the context of First Nations navigating long-term drinking water advisories (LT-DWA). A LT-DWA is a term used to describe when a community’s drinking water system fails to meet the quality standards established by the Canadian Drinking Water Guidelines for a period of more than one year. There are several reasons why drinking water advisories are issued in Indigenous communities. These advisories may be implemented when there are issues with the overall water system, such as water line breaks, equipment failure, or poor filtration or disinfection during the water treatment process. There are three types of LT-DWAs, including boil water advisories, do not consume advisories, and do not use advisories. LT-DWAs can have significant impacts on the affected community, and persistent inaction on remediation can lead to a range of negative outcomes such as higher rates of illness and disease.

While LT-DWAs are a pressing issue for Indigenous communities across the country, the majority of LT-DWAs are occurring in Ontario, many of which have been in effect for years, if not decades. While there have been recent efforts to address this issue, including the federal government’s commitment to end all LT-DWAs by 2023, the persistence of this issue highlights just how entrenched water insecurity is within colonial dynamics with the Canadian state.

In a recent pilot study (Ansloos & Cooper, 2023) aimed at better understanding the relationship between LT-DWAs and suicide rates among First Nations in Ontario, compelling evidence of the lethal cost of settler colonial governmental inaction was found. Between 2011-2016, 50% of First Nations in Ontario with LT-DWAs experienced suicides during the same period, compared to only 15% in in First Nations in Ontario without LT-DWAs. This is a statistically significant difference. This proportion is significantly different from recent census data, which estimated that irrespective of water insecurity, only 29% of First Nations in Ontario reported suicides between 2011-2016. In sum, this study provides evidence that First Nations in Ontario with LT-DWAs were more likely to experience suicide.

Decolonizing Water Governance

The impacts of water insecurity on liveability in Indigenous communities make clear that water is life is not just a cultural sentiment. It is the material stakes of our lives. The proof is both in our grief, and in the data. In affirming the fundamental truth that water is life and recognizing the urgency of protecting and restoring Indigenous relationships to water to address the complex and interrelated challenges of suicide and environmental injustice, we must begin to tether the project of suicide prevention to actionable strategies to enhance Indigenous environmental justice. This requires a decolonizing approach that challenges the structural inequities and power imbalances that shape the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Specifically, this means recognizing Indigenous peoples at the center of the water governance. For too long, water governance in Canada has been centered on colonial power structures that prioritize the interests of the State over Indigenous peoples.

To address water insecurity and its relationship to suicide in Indigenous communities, it is crucial to enhance mechanisms that bolster Indigenous self-determination over water governance. Such an approach must involve upholding and respecting Indigenous peoples’ inherent and treaty rights to water.

Additionally, First Nations can look to the use of legal means to pursue justice for damages related to water insecurity, such as class action lawsuits. The historic settlement agreement resulting from the class action lawsuit led by Tataskweyak Cree Nation, Neskantaga First Nation, and Curve Lake First Nation for damages related to LT-DWAs, which recognized Canada’s failure to provide safe drinking water to First Nations, is a significant step forward. Despite the layers of controversy surrounding the settlement, the agreement’s recognition of the mental health impacts of water insecurity on First Nations and provision of compensation for injuries, including demonstrated impacts on mental health is a positive development that helps to establish precedent for similar circumstances. However, there is a need for further advocacy to address the systemic impacts of water insecurity, including its potential to enhance the risk of suicide by LT-DWAs.

Moreover, the incorporation of mental health and suicide into environmental impact assessments (EIAs) should be prioritized. While some EIAs consider social, cultural, and health impacts, mental health and suicide are largely unexamined in EIAs in Indigenous communities in the North American context. Greater scrutiny over impacts to water systems when prospective projects on First Nations territories are proposed by governments and industry should be required. Demonstrating that water-related environmental impacts might have critical effects on mental health and suicide can support First Nations advocacy for better mitigation of impacts to water systems and water-related infrastructure and community suicide prevention initiatives.

Protecting the Sacred

The Treaty #3 Nibi Declaration, which outlines the Anishinaabe peoples’ understanding of their inherent relationship with water and their responsibility to protect it, provides an excellent example of how Indigenous governance of water can be linked to mental and emotional health and livability more broadly. The declaration states,

WE NEED NIBI IN ORDER TO LIVE A GOOD LIFE All beings, including Anishinaabe, are born of nibi. We depend on nibi to live and our bodies are made of it. Nibi is the source of our wellbeing. It nourishes us, spiritually, physically, mentally and emotionally and provides cleansing and healing. Clean nibi for drinking is important to our health. We must respect our sacred relationship with nibi and all beings in creation to help protect nibi for our children and future generations (White et al., 2019).

The declaration recognizes that water is not a resource for the exploitation of Nestlé, but a fundamental element of life and culture. As such, its governance must be approached with a holistic perspective that incorporates the spiritual, cultural, and ecological dimensions of water. It also highlights that the protection of water is linked to the protection of life. For First Nations living under LT-DWAs and struggling for water justice in the face of the abandonment of the state, a shift towards Indigenous water governance over water management and environmental regulation, holds protective promise with regards to suicide. In other words, we promote life by ensuring water justice. This is why water is life. This is why we must protect the sacred.

Citation: Ansloos, Jeffrey. “Nibi onje biimaadiiziiwin is not a metaphor: The relationship between suicide and water insecurity in First Nations in Ontario” Yellowhead Institute. 3 May 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2023/05/03/suicide-and-water-insecurity/

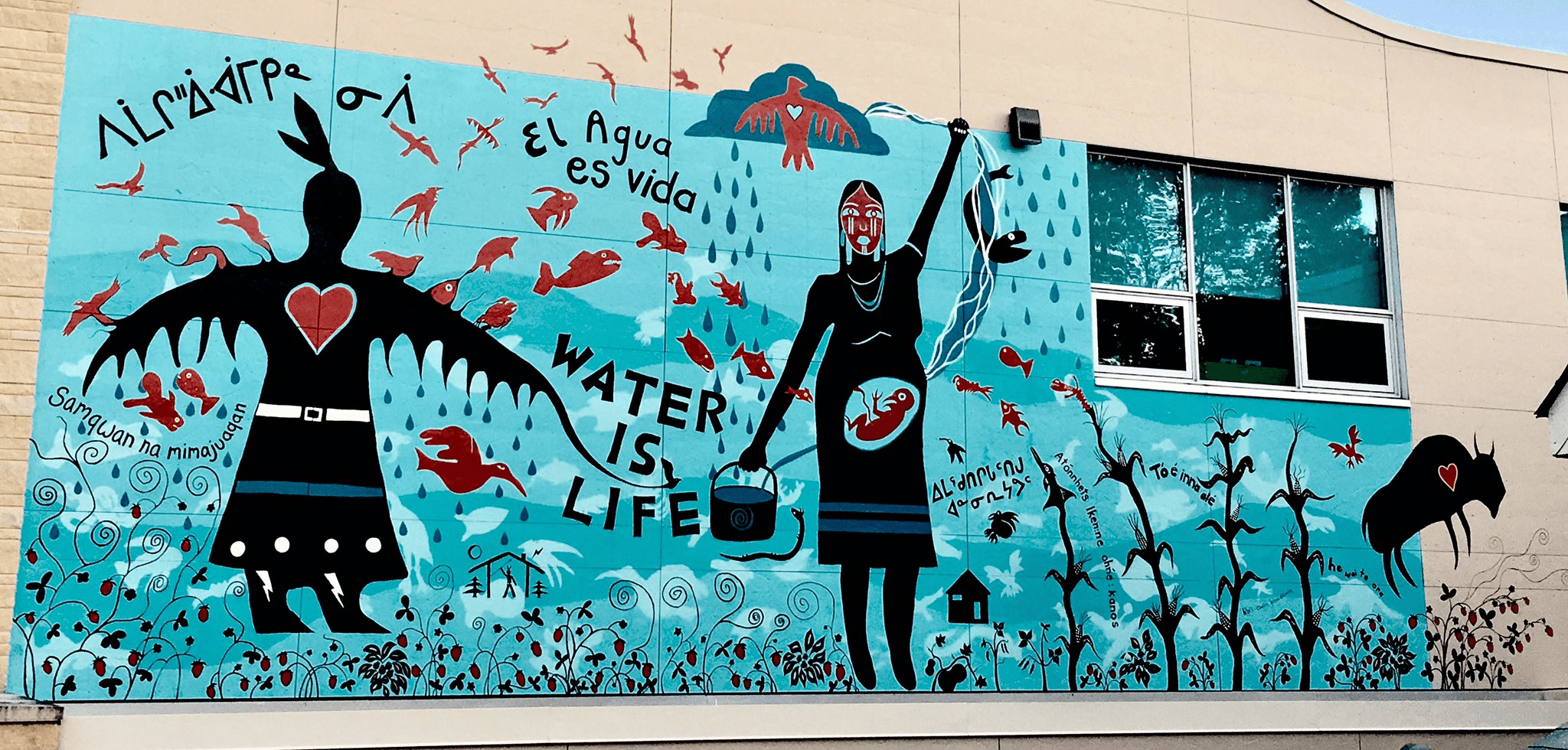

Image Credit: Christi Belcourt, Water is Life mural at Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health in Ottawa

Endnotes

Ansloos, J. (2018). Rethinking Indigenous Suicide. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 13(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v13i2.32061

Ansloos, J., & Cooper, A. (2023). Is Suicide a Water Justice Issue? Investigating Long-Term Drinking Water Advisories and Suicide in First Nations in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054045

Ansloos, J., & Peltier, S. (2022). A question of justice: Critically researching suicide with Indigenous studies of affect, biosociality, and land-based relations. Health, 26(1), 100–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634593211046845

Boyd, D. R. (2011). No Taps, No Toilets: First Nations and the Constitutional Right to Water in Canada. McGill Law Journal, 57(1), 81–134. https://doi.org/10.7202/1006419ar

Cunsolo Willox, A., Harper, S. L., Edge, V. L., Landman, K., Houle, K., & Ford, J. D. (2013). The land enriches the soul: On climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emotion, Space and Society, 6, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.005

Cunsolo Willox, A., Stephenson, E., Allen, J., Bourque, F., Drossos, A., Elgarøy, S., Kral, M. J., Mauro, I., Moses, J., Pearce, T., MacDonald, J. P., & Wexler, L. (2015). Examining relationships between climate change and mental health in the Circumpolar North. Regional Environmental Change, 15(1), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0630-z

Durkalec, A., Furgal, C., Skinner, M. W., & Sheldon, T. (2015). Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 136–137, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.026

Hanrahan, M., Sarkar, A., & Hudson, A. (2016). Water insecurity in Indigenous Canada: A community-based inter-disciplinary approach. Water Quality Research Journal, 51(3), 270–281. https://doi.org/10.2166/wqrjc.2015.010

Kumar, M. B., & Tjepkema, M. (2019). Suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011-2016): Findings from the Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohort (CanCHEC). 99, 23.

McGregor, D. (2018). Mino-Mnaamodzawin: Achieving Indigenous Environmental Justice in Canada. Environment and Society, 9, 7–24.

Redvers, J., Bjerregaard, P., Eriksen, H., Fanian, S., Healey, G., Hiratsuka, V., Jong, M., Larsen, C. V. L., Linton, J., Pollock, N., Silviken, A., Stoor, P., & Chatwood, S. (2015). A scoping review of Indigenous suicide prevention in circumpolar regions. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 74(1), 27509. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v74.27509

Todd, Z. (2017). Fish, Kin and Hope: Tending to Water Violations in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Treaty Six Territory. Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, 43, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1086/692559

White, I., Simard, P., Petiquan, M., Collins, A., & Fischer, R. (2019). The Nibi Declaration of the Women’s Council of the Grand Council Treaty #3. Grand Council Treaty #3. http://gct3.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019-TREATY3-NIBI-TOOLKIT-FINAL-DRAFT-May-2019.pdf