- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- The Rematriation of Indigenous Place Names

- Braiding Accountability: A Ten-Year Review of the TRC’s Healthcare Calls to Action

- Buried Burdens: The True Costs of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Ownership

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

-

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

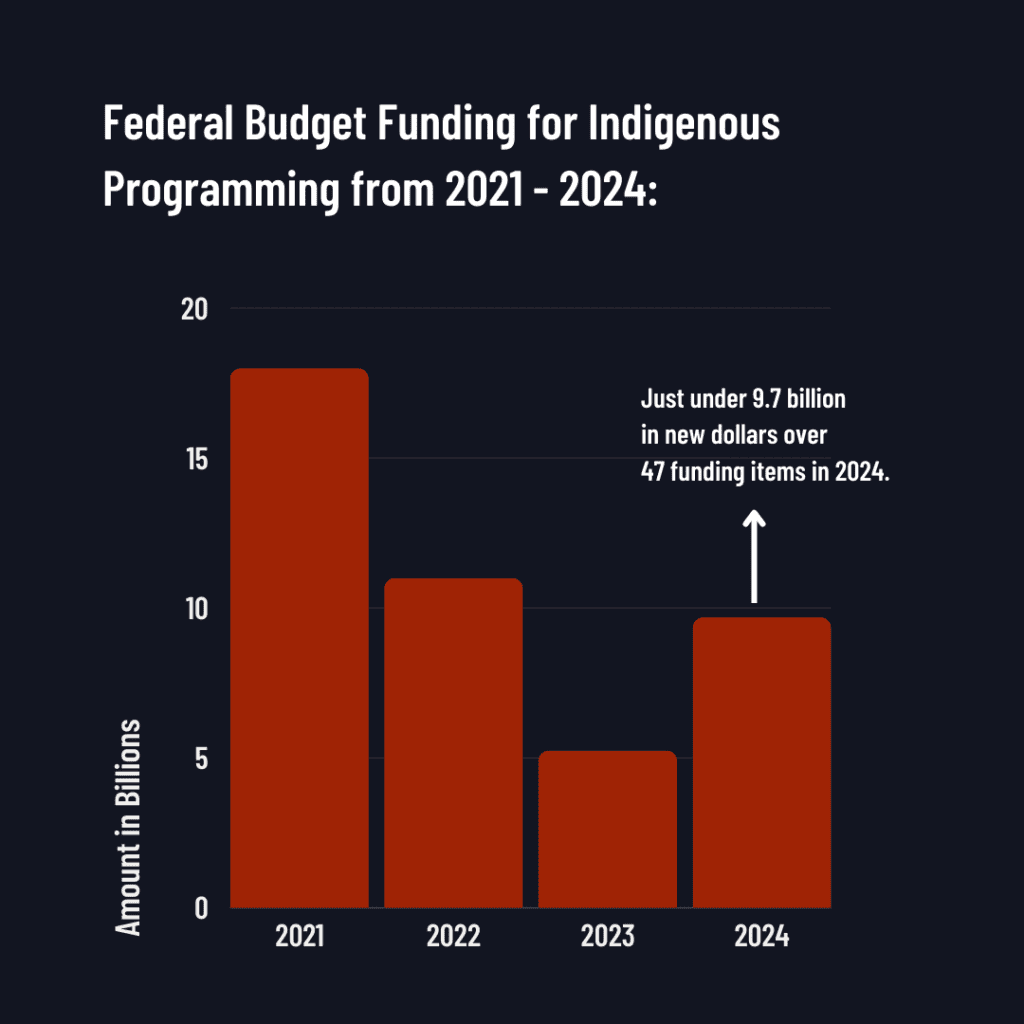

LAST WEEK the Federal Government released its 2024 Federal Budget. With nearly $500 billion in new spending, there is significant funding Indigenous communities: $2.3 billion over five years to fund existing program commitments (p. 280) and an additional $32 billion in spending committed in 2024–25.

That being said, depending on the specific area, this funding is multi-year and, in some cases, extends over a decade. In other words, this is not a single fiscal year allocation, and while it is an increase from last year, it is much lower than the previous Liberal budgets on Indigenous issues.

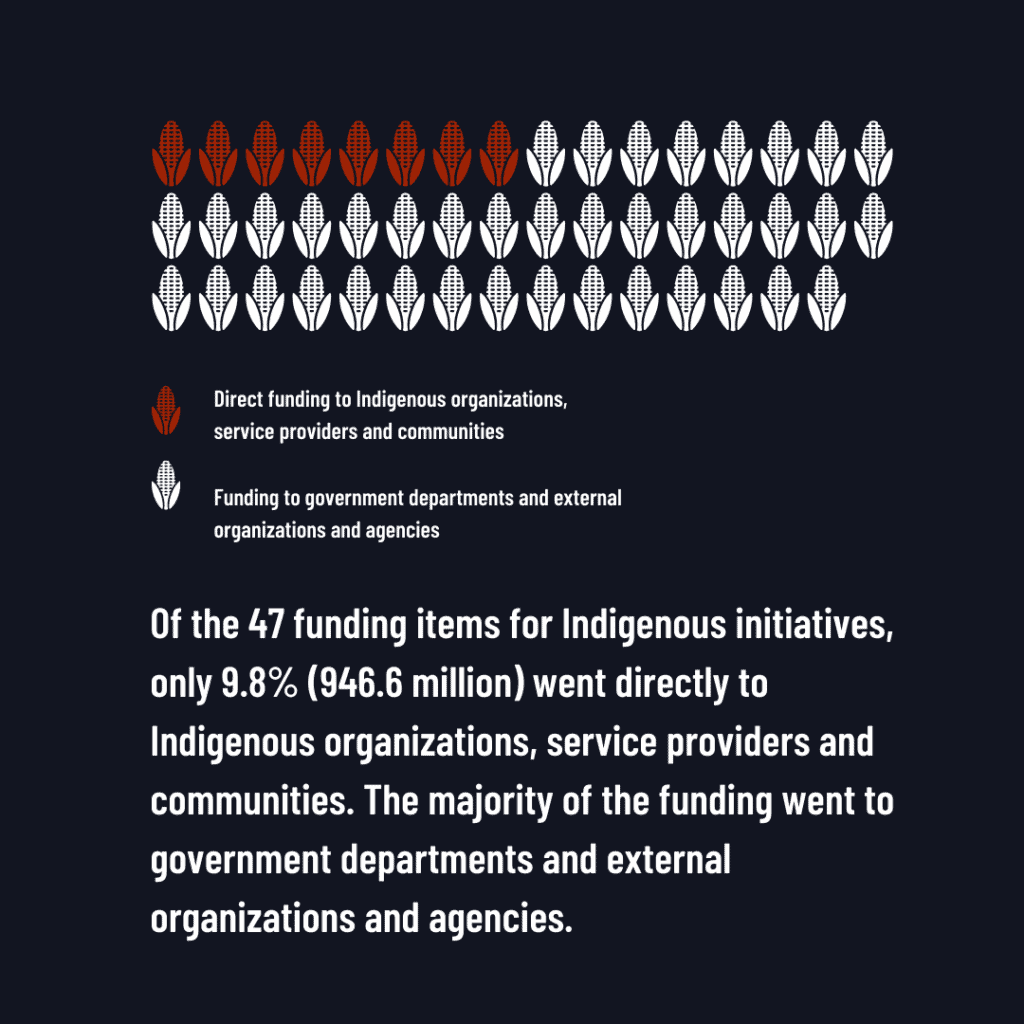

Finally, it is important to note that most of this funding is allocated to departments, agencies, or organizations that aim to support Indigenous communities and not Indigenous communities themselves, which actually receive less than ten percent of this spending.

In this Brief, we highlight some of the notable commitments, the dollar amount, terms of funding, and the page number in the budget document for further review. We have also included analysis from Indigenous experts, within and outside of Yellowhead Institute, on each item discussed. Generally, while there is some welcome new support and innovative policy and program approaches (for better or worse), the chronic underfunding of Indigenous communities that prevents “closing the gap” continues in this budget.

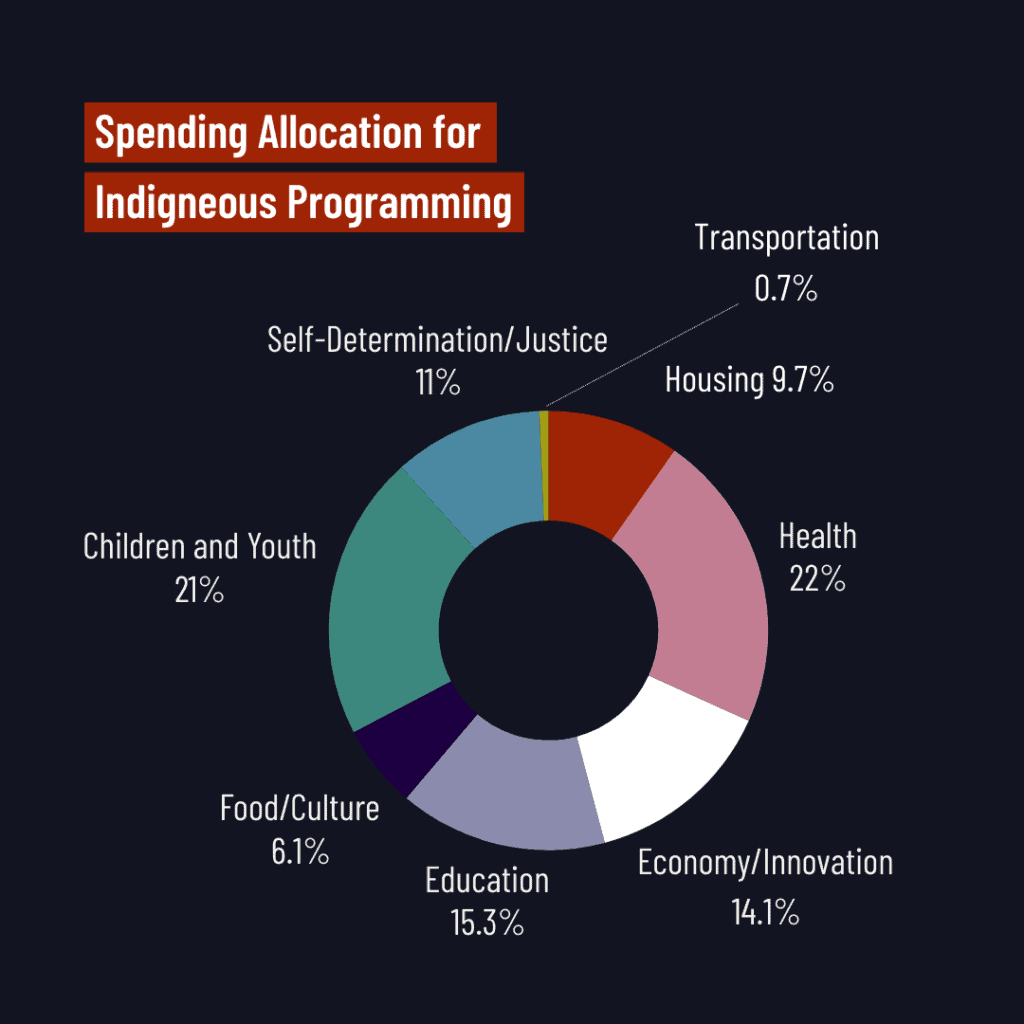

Housing

x

- A total of $4.3 billion over seven years, starting in 2024–25, has been allocated for a co-developed Urban, Rural, and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy. This strategy aims to address housing challenges in urban, rural, and northern communities (p. 82) and provinces are required to commit a significant amount of funding to Indigenous housing.

- $918 million over five years, starting in 2024–25, is committed to accelerate work in narrowing housing and infrastructure gaps across First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities (p. 290).

Just before the budget announcement, The Assembly of First Nations noted that $135 billion is immediately required to address the housing crisis. While significant, this commitment is a fraction of that analysis, prompting Cathy Merrick, Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, to say, “hell will freeze over” before the crisis is actually addressed. More troubling is a Federal Housing Initiative Fund that allows provinces and municipalities “claim” federal lands that can be used to build housing. Indigenous communities have an opportunity — but only after the other levels of government have picked through the options. AFN National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak referred to the approach as “alarming.”

Justice and Safety

x

- A total of $267.5 million over five years starting in 2024–25, and an ongoing $92.5 million annually is directed to Public Safety Canada for the First Nations and Inuit Policing Program and supports the work of Public Safety Canada’s Indigenous Secretariat.

The Auditor General recently reviewed the Policing Program and found a lack of data and oversight, meaning its effectiveness is unclear. (The National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women found that it was not). The Auditor General concluded that “Public Safety Canada did not work in partnership with Indigenous communities to provide equitable access to police services that are tailored to the needs of communities.”

Additional funding for Policing and Justice brings the total committed in 2024 to nearly half a billion dollars. More than spending related to Food, Culture, Transportation, Residential Schools and MMIWG, Environment and Climate Change, and Self-Determination combined.

- $20 million has been pledged in 2024–25 to search the Prairie Green Landfill for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (p. 293).

After months of hesitation, the Federal Government announced earlier this year that it would support the search for the remains of Marcedes Myran, Morgan Harris, and potentially others. Aside from this welcome commitment, there is little else to help families of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, including any substantive support for the implementation of the National Inquiries Calls to Justice, which are currently stalled.

Health and Social Services

x

- A total of $1.8 billion over 11 years, starting in 2023-24, has been allocated for exercising jurisdiction under An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children, youth, and families (p. 288).

A consistent criticism of Canada’s child welfare legislation is the lack of committed resources for First Nations to actually exercise jurisdiction in this area. On its surface, this commitment addressed those concerns; however, being spread across 11 years means a long-term commitment but a small annual amount that it is insufficient and likely actually unpredictable, given that multiple future governments will need to carry it through.

- $167.5 million over two years, starting in 2023–24, is allocated for the Inuit Child First Initiative (p. 288).

Flowing out of Jordan’s Principle, which NDP MP Lori Idlout has raised concerns about, warning that the federal budget will cut funding for Indigenous supports, the Child First Initiative supports Inuit families facing discrimination in a variety of social policy areas. In 2023, APTN reported that CFI was overwhelmed with requests for support and that families were facing long delays by the Federal Government to have their requests approved (or denied).

Economic Development

x

- $350 million over five years, starting in 2024–25, has been pledged to renew Canada’s commitment to Indigenous Financial Institutions (p. 287).

While it will be deeply unpopular among many who operate smoke shops and dispensaries, the Federal Government is committing funding for an opt-in tax collection program — advocated for many years by the First Nation Tax Commission — that would allow communities to tax fuel, alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco and help offset some of the costs incurred by communities for hosting these businesses.

- Up to $5 billion in loan guarantees is available to support Indigenous economic participation in natural resource and energy projects (p. 287).

Since at least 2007, the economic development philosophy of successive Federal Governments has been joint ventures between resource companies and Indigenous communities. With limited restitution-based initiatives, Canada instead has developed a process to bring Indigenous people more closely into resource development, potentially unlocking a backdoor to issues of free, prior, and informed consent in the process and outsourcing their fiduciary obligations to industry.

- $65 million over five years, starting in 2023–24, has been allocated for a First Nations-led land registry and to support capacity in managing lands and resources (p. 287).

As interest grows in the First Nation Land Management Act (FNLMA) and Land Code process, the related infrastructure for surveys, dispute resolution, and the internal privatization of reserve lands is also required. With the potential revitalization of market-based housing, the possibility of a future Conservative Government, and proposals for more expansive private property initiatives, a registry will be required. There has been limited evaluation of the effectiveness of the FNLMA.

Indigenous Education

x

- $242.7 million over three years, starting in 2024–25, is for First Nations post-secondary education, with an additional $5.2 million over two years starting in 2024–25 to support the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning (p. 280).

While any post-secondary support is, of course, welcome, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. specifically requested support for Inuit post-secondary education as options continue to be developed for Nunavut-based University programming; however, the request was not acknowledged. Meanwhile, the Federal Governments have a habit of selecting and funding discrete education programming initiatives that aim to support Indigenous communities: The Martin Family Initiative, Teach for Canada, Indspire, etc. This year’s recipient of federal recognition is the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning, which has been waiting with bated breath.

Urban, Language & Culture

x

- $60 million over two years, starting in 2024–25, will support Friendship Centres across the country (p. 287).

This is an important increase in funding for Friendship Centres across the counties; it will allow the historically underfunded but critically important organizations to expand their operations — but only for the next two years. There is no committed funding for Friendship Centres beyond 2026. The National Federation of Friendship Centres will also likely receive some support for mental health programs and the Red Dress Alert.

- $5 million over three years, starting in 2025–26, will go to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada to establish a program to combat Residential School denialism (p. 284).

This is a deeply depressing funding commitment to address the ongoing racism of Canadians toward Indigenous people. Following previous Federal commitments to recognize National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (one of the few implemented TRC Calls to Action), this fund seeks to “combat” Residential School denialism. Earlier this year, Independent Special Interlocutor on Unmarked Graves, Kimberly Murray, identified the rise of this denialism.

- $225 million over five years, starting in 2024–25, is for Indigenous languages and cultures programs (p. 280), and $65 million over five years, starting in 2024–25, will support the Indigenous Screen Office (p. 287).

Even before the 2019 Indigenous Languages Act was passed and the Office of the Indigenous Language Commissioner was established (which was only last year), there were loud criticisms of the Federal Government’s approach to language revitalization. A central critique has been a lack of funding to save the languages Canada is destroying. While the sustained funding will support revitalization initiatives, it is a small fraction of the funds required to make a difference. But, on the upside, we’ll get more Indigenous movies.

Citation: King, Hayden and Yesno, Riley. “Federal Budget 2024: An Indigenous Accounting”. Yellowhead Institute. 22 April 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2024/04/22/budget-2024/