- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Pretendians and Publications: The Problem and Solutions to Redface Research

- Pinasunniq: Reflections on a Northern Indigenous Economy

- From Risk to Resilience: Indigenous Alternatives to Climate Risk Assessment in Canada

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- The Treaty Map

- LIBRARY

- Submissions

- Donate

KEY LINKS:

Part 1: Why are the Laws on the Role of the Department(s) Important?

Part 2: What’s in the Department of Indigenous Services Act (“DISA”)

that is helpful?

a) Sets out important commitments by Canada

b) Identifies the groups the department serves

c) Lists the main activities and responsibilities to be undertaken by the departments

d) Annual reporting requirement

ON JULY 15, 2019, two new federal laws came into effect: the Department of Indigenous Services Act (“DISA”) and Department of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Act (“CIRNAA”).Together, these two acts replaced and repealed the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, RSC 1985, c I-6 (the “DIAND Act”).

As draft bills debated in Spring 2019, these got very little attention in comparison to federal bills on Indigenous Languages or Indigenous Child Welfare. This is likely due, in part, to the fact that these new bills were hidden (at Division 25 of Part 4) in a big omnibus budget implementation bill called Bill C-97 An Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on March 19, 2019 and other measures.

The main purpose of these laws was to make legal the administrative changes announced by Canada in September 2017 that it was replacing the Department of Indian Affairs Canada (“INAC”) with two new federal departments, namely Indigenous Services Canada (“ISC”) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs (“CIRNA”).

The government announced this split in INAC in order to have ISC focus more specifically on improving the quality of services delivered to Indigenous peoples, with the long-term objective of ensuring Indigenous Peoples move to self-government, while CIRNA would focus on achieving a better whole-of-government coordination of the nation-to-nation relationship and developing a framework to advance a recognition-of-rights approach. At the time, although acknowledging this change was consistent with recommendations from the 1996 Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal Peoples (“RCAP”) that I generally support, I questioned the timing and the fact that this was not being implemented alongside many more important recommendations made by RCAP. Others raised concerns about the motive behind this change as well.

Another reason these laws might have gotten little attention this past spring is that their content does not seem that ground-breaking—just putting into place the legal mechanics to run two departments instead of one. It’s not like these laws repealed or changed anything in the Indian Act, after all. True, but laws that set out the details of the government’s relationship with Indigenous peoples can be important. My aim here is to explain this and how the new laws, particularly DISA, is an improvement over the old DIAND Act. (I will leave detailed discussion of what CIRNAA for another day).

I believe Indigenous communities can use what’s in this new law to their advantage.

1. Why are laws on the role of the department(s) important?

In a nutshell, the answer is that such laws can place limits on what the federal government can do and can be used to make it more accountable to Indigenous peoples. There has been a lack of such limits and government accountability in the past.

While the Indian Act has allowed the federal government to exercise significant control over several aspects of First Nations peoples’ lives, including over lands, monies, governance, Indian status, wills and estates, and education (at least during the Residential and Indian Day School periods), there are also a bunch of areas that the Indian Act doesn’t cover (the last time it updated was in 1951!). These areas include essential services areas like child welfare, social assistance, assisted living, day care, community health services, modern education, housing, policing, water services, infrastructure and emergency services. The federal government tried to delegate most of this to the provinces in 1951 through s. 88 of the Indian Act, but this was mostly unsuccessful. (In a few cases like child welfare and policing, the provinces do provide these services, but on the condition that the federal government pays the majority of provinces’ costs).

Despite its reluctance, the federal government has been providing most of the above-noted services to First Nations starting in the 1960s. But the government did not want to pass any laws in order to do this (which would have been the expected thing to do). Instead, the federal government has provided such services over the years through a combination of treasury board authorities, program policies and since the 1990s, and using funding agreements to delegate the delivery of such services to First Nation governments (known as ‘program devolution’).

Although many of our people see Canadian laws as tools of governments to limit or take away Indigenous peoples’ rights (and for very good reason given the history of the Indian Act!), laws can also operate to put limits on governments.

In fact, this is, in part, what the concept “the rule of law” means in Canada—that laws apply to governments and limit what they can do. So, what we had with INAC for over 50 years is a department operating in many areas where there is no law setting out how it is supposed to act and what it can or can’t do. There’s not even anything in the Indian Act or the DIAND Act generally setting out the roles and responsibilities of the department, or its purpose or objectives. In fact, the only thing the DIAND Act does is recognize that the Minister and the department have powers in relation to “Indian affairs.” That’s it! Although INAC has operated in this way for some time, in fact, this is not a normal way for a government to operate. For most major government services, there are normally laws that set out not only who is eligible for the service and programs terms but also set out objectives of the program and government responsibilities.

Over the years, the lack of laws over the various services that INAC provides to Indigenous peoples has led to uncertainty and confusion about what the department can and cannot do. Policies and funding agreements do not have the same force as laws and give much more room for INAC to manoeuvre. This uncertainty has allowed different government administrations to change—sometimes drastically—how services are provided to First Nations.

With no limits set out in law, it can be very difficult if not next to impossible to challenge the government (even if the changes cause harm to First Nations).

As a lawyer, I represented First Nations in the Maritimes from 2011to 2015 who fought a change in INAC’s Income Assistance Program introduced by INAC under Stephen Harper’s Conservative government. The case was called Simon v. Canada (Attorney General, which we won at the federal court, but lost on appeal. INAC proposed to interpret its treasury board authority to fund Income Assistance in a much narrower way than previous governments. Documents obtained during the court case showed that regional staff recognized this would result in a significant reduction in basic income for welfare recipients on reserve (whose benefits were already less than recipients on provincial welfare), and staff predicted this would likely lead to violence in the communities, a human rights complaint, and increase in child apprehensions in communities. Nonetheless, INAC was prepared to move ahead with the changes. Even with such evidence, it was difficult to challenge this change in the courts.

A major reason for this was the fact that there were no real limits set out in law about how INAC could run the program. There was no definition of program terms or anything spelling out program objectives that we could point to argue that what INAC was trying to do was wrong.

Where there are no clear limits set out in law, courts are generally hesitant to impose strict rules on governments, especially when spending is involved. Overall, the courts are often very deferential to the government where there are no clear legal rules governing their conduct.

Evaluations of INAC over the years also show us there is a problem here. A 2005 internal evaluation and a 2008 study by the Institute on Governance found that INAC really has no clear objective driving it with respect to administering services to First Nation and that INAC staff are unclear on whether their overall objective is to promote Indigenous well-being and help communities transition to self-government, versus monitoring First Nations and ensuring they are compliant with minimum program standards under funding agreements and file all necessary reports and audits. Because of this confusion, we see the department fluctuate dramatically in its approach between different government administrations. Evaluations of INAC at the end of the Harper era found that INAC staff clearly saw their main objective as monitoring and compliance and not the priorities of First Nations.

My point here is that having laws that set out expectations and roles or obligations of government departments can be used by those on the receiving end of those services to hold government accountable.

2. What’s in the Department of Indigenous Services Act (“DISA”) that is helpful?

Unlike its predecessor, the DIAND Act, which provided no guidance or limits whatsoever on the department, DISA actually includes some content about ISC’s objectives and responsibilities and introduces some things that can be used to place limits on the department’s conduct. The law isn’t perfect (for example, I would have liked to see a dispute resolution mechanism and some language around the requirement to adequately fund programs), but there is definitely more to work with here than before, and this is helpful for Indigenous peoples.

a) Sets out important commitments by Canada

First, DISA contains three important commitments by the Government of Canada within its preamble. They are as follows:

Whereas the Government of Canada is committed to

[1] achieving reconciliation with First Nations, the Métis and the Inuit through renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government and Inuit-Crown relationships based on affirmation and implementation of rights, respect, cooperation and partnership,

[2] promoting respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and

[3] implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Preambles are legally significant because of the law on the interpretation of statutes. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, a law has to be interpreted in ways that consider not just the particular section of the law in question, but the rest of the text of the law (including the preamble), the context and the purpose the government had in enacting the law. So when considering what the obligations of the department are, the courts can look to the preamble of DISA to supply principles and values that ISC should be bound by.

To put it another way, the inclusion of these commitments in the preamble of DISA means that the actions of ISC should be consistent (and not inconsistent) with these commitments.

For example, if DISA existed at the time of the Simon case, I would have had firmer ground to argue that the interpretation of the treasury board authority taken by the Harper administration, by causing significant harm to First Nation welfare recipients, was inconsistent with Canada’s commitment to reconciliation and various provisions in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that confirm Indigenous peoples rights to social and economic security and require states to take special measures to ensure continuing improvement of their economic and social conditions.

Although the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples already applies within our legal system because courts should interpret Canadian laws to be consistent with international human rights law, the reference in the preamble of both DISA and CIRNAA is nonetheless helpful because they evidence a clear intention by the government of Canada to be held to the standards in the Declaration in the work of ISC. In disputes with the department, politicians, bureaucrats and judges should be reminded of that.

b) Identifies the groups the department serves

DISA defines the communities it serves, using the overarching term “Indigenous peoples” and states that it has the same meaning as “Aboriginal peoples” within subsection 35(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982. Section 35(2) defines “Aboriginal peoples of Canada” as including the “the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.”

In addition, the acts define “Indigenous governing body” as meaning “a council, government or other entity that is authorized to act on behalf of an Indigenous group, community or people that holds rights recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.” The acts also define the term “Indigenous organization” as meaning “an Indigenous governing body or any other entity that represents the interests of an Indigenous group and its members.”

The DIAND Act never explicitly defined the group it serviced, although its name strongly suggested it exclusively served ‘Indians’ (today the term “First Nations” is used more commonly).

Indeed, for the last 152 years, the government of Canada has tried to limit its responsibilities to First Nations living on reserve, but a number of court decisions over the years have found that Canada also has jurisdiction (and responsibilities to) Inuit people, First Nations living off-reserve, and most recently Métis and non-status Indians (e.g., non-status First Nations people).

It now appears Canada is more willing accept a more inclusive definition of the communities it services by using the term “Indigenous peoples.” That said, DISA slyly tries to do a bit of end-run around this by limiting its service-delivery to those who “are eligible to receive those services under an Act of Parliament or a program of the Government of Canada for which the Minister is responsible” (s. 7(b) of DISA).

In other words, DISA limits its service delivery to those who are eligible under ISC program policies.

ISC policies tend to be limited to First Nations living on-reserve. So, there’s a tension between the policies and the more inclusive language in DISA. This will likely lead to a Charter or human rights challenges to programs that limit services just to on-reserve First Nations. Given past court decisions, the fact that the act embraces a more inclusive definition of who is Indigenous, my bet is on the courts finding that ISC owes services to a broader group of Indigenous people.

c) Lists the main activities and responsibilities to be undertaken by the departments

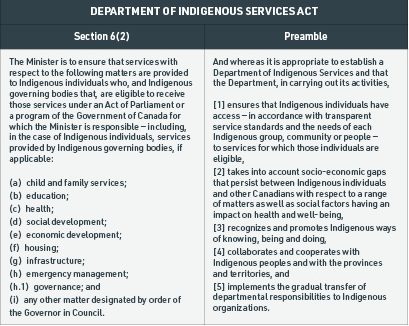

Unlike the DIAND Act, the DISA give us a clearer sense of what ISC is expected to do. We find information in both the preamble and main texts of the law on this. Here is the actual text:

So, what we see first, in s. 6(b), is a list of the essential services ISC is responsible for providing, and the preamble supplies principles that should guide ISC in the provision of these services. (Note that policing services and justice are missing from this list because they are services administered to Indigenous peoples by the departments of Public Safety and Justice.)

I will first note that it is remarkable to see a list of services over which the Minister/department is “to ensure that services … are provided Indigenous individuals … .”

Subject to what I said earlier about ISC policies trying to limit services to First Nations, this is legal recognition by the federal government of its responsibility to provide the listed essential services to Indigenous peoples. I am happy to see this because, for the longest time, INAC and Crown lawyers would argue that Canada did not have any legal responsibility to provide such services, but rather, provide such services merely as a matter of good public policy. Such arguments were used to minimize Canada’s obligations towards First Nations. Given this acknowledgment, such minimizations should no longer be possible.

The guidance in the preamble about how ISC should carry out the delivery of these services is also remarkable. (Recall my comments above about the legal significance of preambles: they, like the rest of the text of DISA, must inform ISC’s actions). I see seven significant requirements on ISC imposed by this preamble:

- ISC’s service standards should be transparent [#1]

- ISC’s services should meet the needs of Indigenous group (e.g., be ‘needs-based’) [#1]

- ISC has to take into account the socio-economic gaps and negative social factors impacting Indigenous individuals in doing its work [#2]

- ISC has to be concerned with Indigenous individuals’ health and well-being [#2]

- ISC should recognize and promote Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing [#3]

- ISC should collaborate and cooperate with Indigenous peoples in its work [#4]

- ISC should work towards the gradual transfer of its responsibilities to Indigenous organizations (i.e., self-government) [#5]

What is called for in the preamble is a vast improvement over how INAC has generally operated in the delivery of services to First Nations based on my experience and research. Many of INAC’s program standards are not transparent—many of the program policies are not available or accessible online. For example, I had a student who was writing a paper on First Nations housing two years ago who was forced to make a special request to INAC to get a copy of its Housing Policy and what she got back a hard copy policy from 1996 that still had ‘draft’ written on it! In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, First Nations are using regional social assistance policies that exist only in hard copy and haven’t been updated since 1994!

Nor are program standards currently needs-based or reflective Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing—program and funding standards have based on provincial standards according to treasury board authorities since the 1960s.

In 2016, Canadian Human Rights Tribunal found the mirroring of provincial rates and standards in the provision of child welfare services on reserve to be discriminatory in the Caring Society decision. The Tribunal found, that as a matter of human rights and equality law, First Nations children and families are entitled to services meet “their cultural, historical and geographical needs and circumstances.” I have argued that this requirement applies to all services, not just child welfare.

For a very long time, INAC has done nothing about the fact that its own service delivery is responsible for exacerbating the socio-economic gaps experienced by Indigenous peoples and in so doing was callously ignoring their health and well-being. The Tribunal in the Caring Society case found that INAC had been knowingly underfunding child welfare services on reserve for over a decade. Evidence on this included an internal INAC 2006 document called Explanation on Expenditures of Social Development Programs, where the department described all of its social programs as “…limited in scope and not designed to be as effective as they need to be to create positive social change or meet basic needs in some circumstances.”

The Tribunal in the Caring Society case found that INAC had been knowingly underfunding child welfare services on reserve for over a decade. Evidence on this included an internal INAC 2006 document called Explanation on Expenditures of Social Development Programs, where the department described all of its social programs as “…limited in scope and not designed to be as effective as they need to be to create positive social change or meet basic needs in some circumstances.”

At times, INAC was resistant to claims that it had any legal obligation to collaborate and cooperate with Indigenous peoples.

In the Simon case I referred to earlier, First Nations in the Maritime were told by INAC that the department had no legal duty to consult with the First Nations over its change to the Income Assistance Program since welfare is not an Aboriginal and treaty right protected s. 35 of the Constitution Act that Canada must consult on (which is true on the narrow interpretation of s. 35 given by the courts to date, but not if you interpret s. 35 in harmony with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

In any event, we were successful at the lower court in arguing that Canada nonetheless had a duty to consult with the First Nations based on administrative law concepts of procedural fairness, interpreted consistently with the Declaration.

In addition to what’s in the preamble, section 7(a) of DISA specifically states that the Minister has the responsibility to “provide Indigenous organizations with an opportunity to collaborate in the development, provision, assessment and improvement of the services referred to in subsection 6(2).”

Remember, “Indigenous organization” would not just include National or Provincial Indigenous organizations like the AFN or provincial affiliates, but includes “Indigenous governing bodies” that is broadly defined as “a council, government or other entity that is authorized to act on behalf of an Indigenous group, community or people that holds rights recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.”

So, it would now seem that ISC is now required to consult with Indigenous groups when it creates, changes or assesses its services.

Finally, DISA’s preamble states that ISC must strive for the gradual transfer of its responsibilities to Indigenous organizations. In other words, this tells us that the end-goal for ISC should be self-government in relation to the services listed in the act. On the one hand, this is positive because it’s clear now that ISC has to be concerned about Indigenous health and well-being and its main objective is to support self-government. This addresses the problem I noted earlier, where it was not clear whether INAC’s role was to promote Indigenous self-government versus monitor compliance with funding agreements. Note that there is nothing in DISA about monitoring and compliance being objectives of the department. That said, as a matter of government accountability we can expect that ISC will still continue monitor funding agreements, but the point is that this can’t become ISC leading priority (as it seemed to be in the Harper era and could become again if Conservative government is elected).

On the other hand, some might not like the language of “gradual transfer” as Indigenous people have the inherent right to self-determination and should be self-governing now without the approval of Canada. However, Canada has long taken the position that the exercise of self-government has to happen via agreement. DISA continues to be consistent with this approach by requiring, at section 7(b) that transfers of responsibilities have to happen through agreements (and section 9 gives the Minister the power to enter such agreements). (I have been critical of such piecemeal approaches and proposed revisiting proposals in the 1996 Royal Commission Report to implement self-governments nationally. But I have also written about how First Nations can exercise control over essential services now through the passing of bylaws as a temporary measure.)

d. Annual reporting requirement

Along with the guidance that ISC must be mindful of addressing socio-economic gaps and Indigenous health and well-being and support Indigenous groups’ transition to self-government in the preamble, section 15 of DISA imposes a requirement of ISC to annually table a report in Parliament (three months after the end of the fiscal year or, if the House is not then sitting, on any of the first 15 days of the next sitting of the House) on:

(a) the socio-economic gaps between First Nations individuals, Inuit, Métis individuals and other Canadians and the measures taken by the Department to reduce those gaps, and

(b) the progress made towards the transfer of responsibilities

It goes without saying that no similar reporting requirement existed in the DIAND Act.

I believe this provision is significant for a couple of reasons. First, it reinforces the fact that ISC’s primary mandate is to reduce socio-economic gaps and promote self-government and makes it clear that ISC has to take action in this regard because it has to report on “the measures” it took and the “progress” it has made. Second, as is clear from the review of several Auditor General of Canada reports above, INAC consistently resisted measuring and reporting on whether its services were meeting department objectives. Now there is a clear requirement for ISC to do this, and these reports, since they will be tabled in Parliament, will be public documents available to everyone. This will help in keeping ISC accountable.

Conclusion

To sum up, if ISC lives up to the standards set out in DISA (which it is now legally obliged to do, and which Indigenous communities can now push the department on), this should result in major changes in terms of its predecessor has operated. True, change can be slow within the federal bureaucracy, but communities can demand more now that these standards are set out in law.

Citation: Metallic, Naiomi W. “Making The Most Out Of Canada’s New Department Of Indigenous Services Act.” Yellowhead Institute, 12 August 2019, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2019/08/12/making-the-most-out-of-canadas-new-department-of-indigenous-services-act/