- About

- Research

-

-

- Special Reports & Features

- Twenty-Five Years of Gladue: Indigenous ‘Over-Incarceration’ & the Failure of the Criminal Justice System on the Grand River

- Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation

- Data Colonialism in Canada’s Chemical Valley

- Bad Forecast: The Illusion of Indigenous Inclusion and Representation in Climate Adaptation Plans in Canada

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Ontario: A Study of Exclusion at the Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs

- Indigenous Land-Based Education in Theory & Practice

- Between Membership & Belonging: Life Under Section 10 of the Indian Act

- Redwashing Extraction: Indigenous Relations at Canada’s Big Five Banks

- Treaty Interpretation in the Age of Restoule

- A Culture of Exploitation: “Reconciliation” and the Institutions of Canadian Art

- Bill C-92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Children, Youth and Families

- COVID-19, the Numbered Treaties & the Politics of Life

- The Rise of the First Nations Land Management Regime: A Critical Analysis

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Lessons from B.C.

- View all reports.

- Special Reports & Features

-

-

- Yellowhead School

- LIBRARY

- Contact

- Submissions

- Donate

SINCE THE ESTABLISHMENT of Alberta’s First Nations Gaming Policy in 2001, Indian Gaming in the province has been a much discussed topic.

To date, a majority of the discussions and questions revolve around the way revenue generated on-reserve through gaming is distributed. This is an important conversation, and one that requires a renewed debate on how the revenue is shared. This Brief considers the current formula, highlights some inequities, and hopefully opens the space for more critical questions.

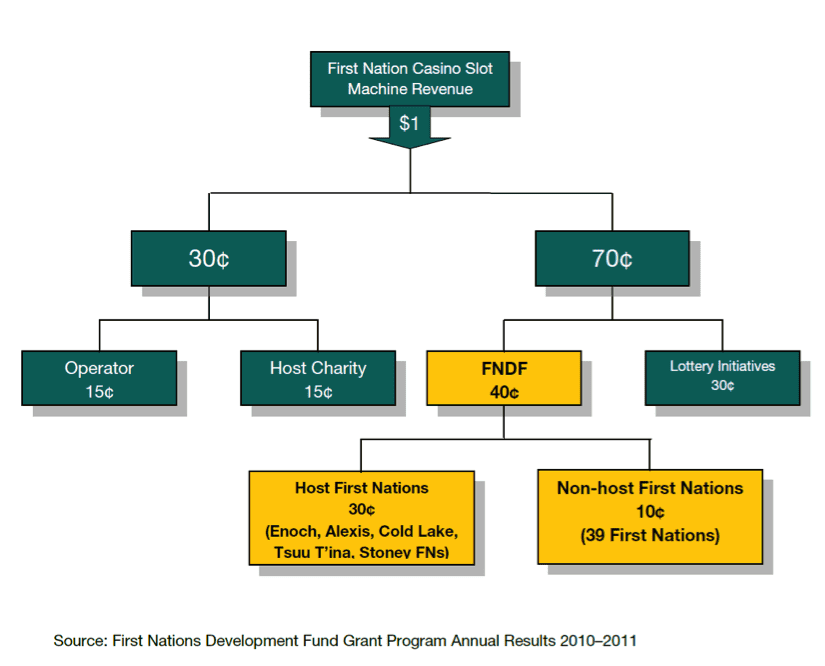

Beginning in 2006 with the opening of the Rivercree Resort and Casino located on the Enoch Cree Nation, proceeds from government-owned slot machines have been allocated in a 30/70 split, which ultimately breaks down to a 30/40/30 split. Revenues from table games are not subject to these splits and are allocated to the host communities charity in much lower amounts. The chart below describes the breakdown of the slot revenue allocation:

As shown above, for every dollar earned, 30% is returned to Host Nations (Casino Operators), 40% is invested into the First Nations Development Fund (FNDF), and the final 30% is invested into the Alberta Lottery Fund (ALF).1 This deal, appearing very beneficial to host communities on the surface, includes an “unexpected proviso” of allocating 30% to the Alberta Lottery Fund. As outlined by Drs. Yale Belanger and Robert Williams in 2012, this proviso supports non-Indigenous programming.2

To elaborate, gaming revenues allow Host communities to support a variety of projects ranging from long-term financing, construction, housing, recreation and economic development.

The FNDF is an application-driven grant program that allocates the 40% of revenues to projects in First Nations communities to address chronic underfunding in areas of economic, social and community development. The remaining 30% remains in the ALF and is spread across eleven ministries for a variety of programs benefiting everyday Albertans and supporting various community initiatives.4

This is problematic.

Given the poor state of infrastructure and economies in First Nations communities, Belanger and Williams argued that the Province of Alberta should reconsider its 30% take from the First Nations casinos and redirect it back into the First Nations Development Fund, minus administration of the gaming legislation.5 This conclusion was based upon the reality that First Nations comprise 3% of the Alberta’s population, contributed +25% to the ALF, but accessed just 0.12 percent of available charitable monies during the period 2006–11.

Accessing so little while contributing so much of the ALF ($284,322,077) creates an impression – but very likely a reality – of limited access for First Nations to the ALF.6 This is deeply unfair.

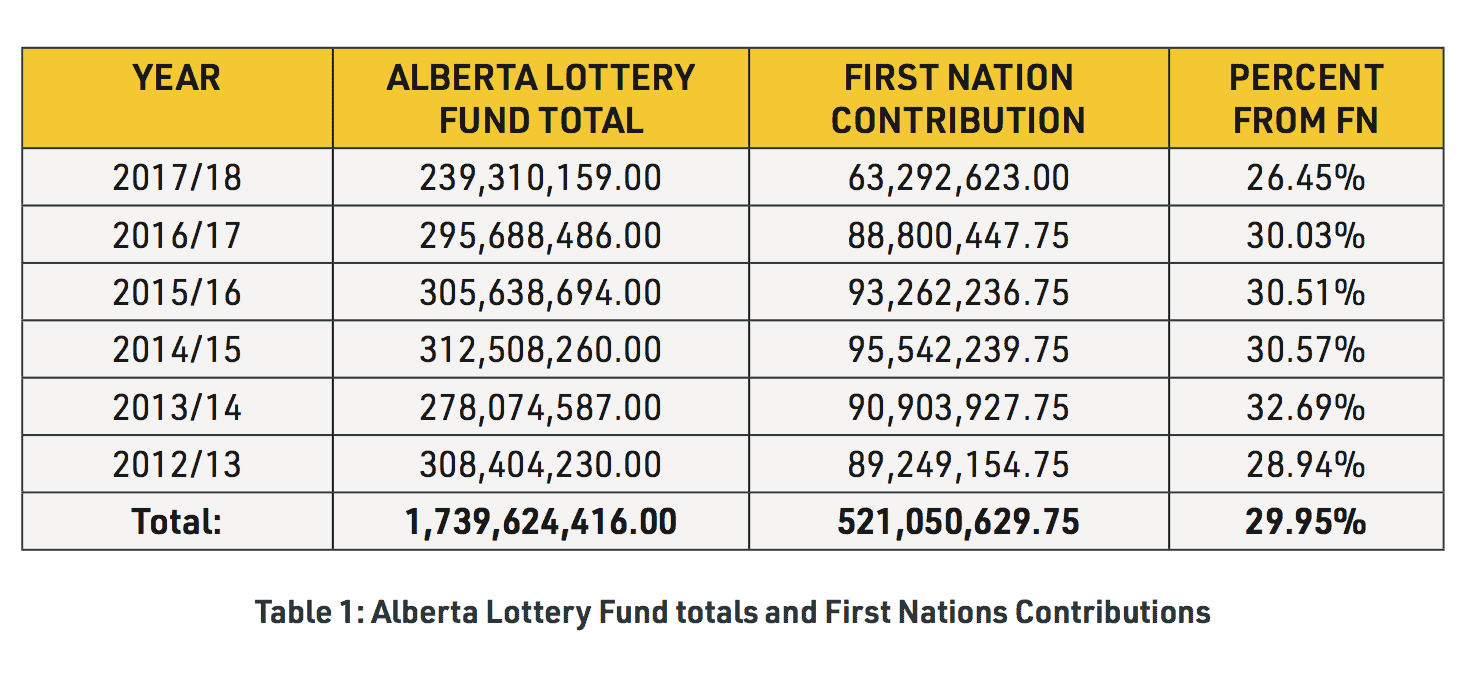

Many have shared this sentiment. There is the Auditor-General’s report cited above, numerous calls to action, requests for review,7 and a resolution passed at the 2013 Assembly of Treaty Chiefs. More, we have data that shows that the allocation of ALF grants to First Nations communities have not shown improvement since 2012. Below is an overview of the First Nation contributions to the ALF. And further down, an overview of the rates of at which First Nations in Alberta access the ALF.

During their review, Belanger and William calculated that the highest First Nation’s gaming contribution to the ALF before 2012 was 25%. Since 2012, this contribution has risen to as high as 32%. On average, First Nations have propped up the Alberta Lottery Fund with contributions totalling $521,050,629.75, from 2012-2018. This amounts to 30% of the overall ALF amount.

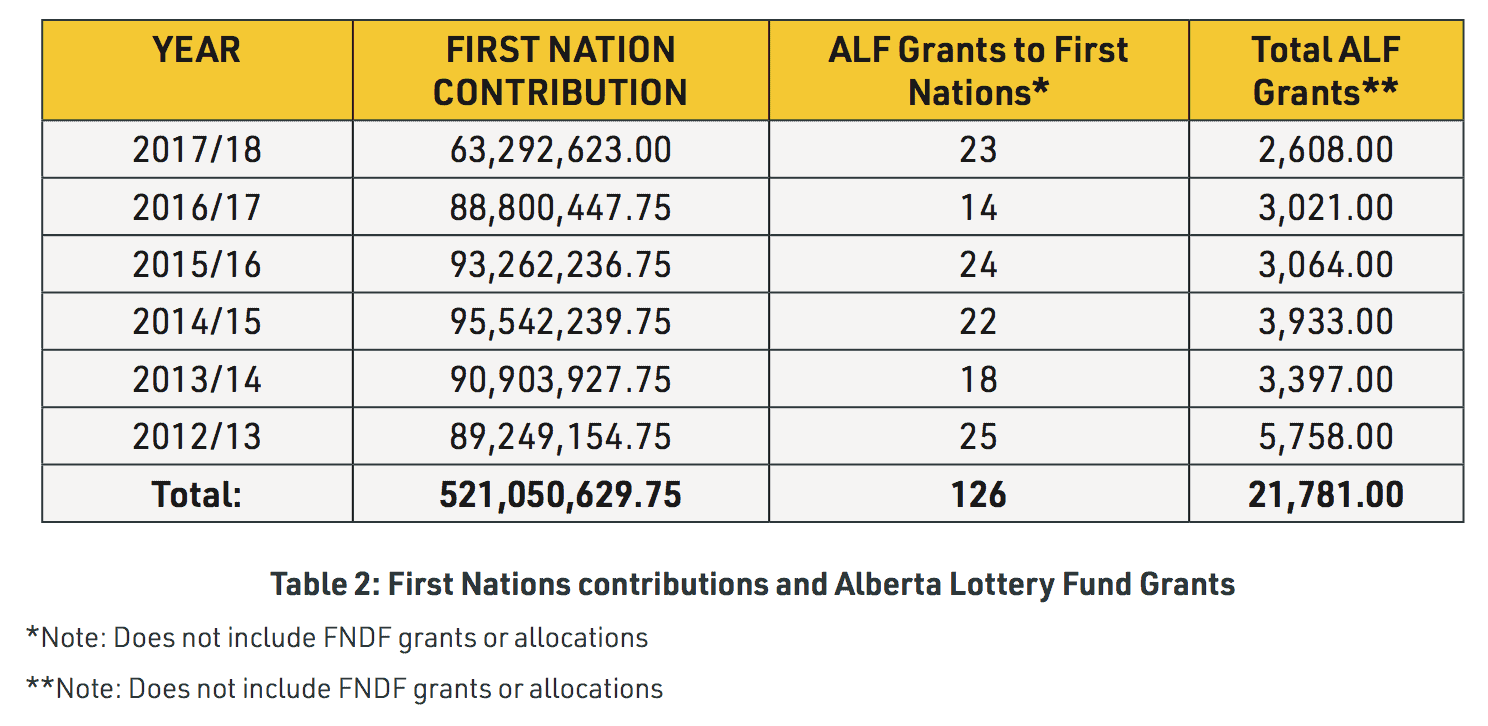

As stated earlier, given these dramatic numbers, it should be expected that First Nations correspondingly access the ALF. But that is not actually the case.

The number of First Nations accessing ALF grants has remained consistently low. In comparison to their contributions, First Nations have only been granted 126 of 21,781 ALF grants between 2012-2018. This amounts to a staggeringly low 0.005% of all Alberta Lottery Fund grants, excluding FNDF, being allocated to First Nations communities.

For a fund open to all communities and organizations in Alberta, it seems unrealistic that First Nations people or communities submit so few projects. Over the years, there have been many conversations and claims that First Nations regularly apply for ALF dollars, only to be redirected to the FNDF programming. While this is anecdotal, the Alberta Government has yet to release data confirming or refuting the claim that First Nations are rejected more often in their proposals to the ALF.

While there have been political discussions on the periphery of this issue – addressing gaps and finding ways to alleviate deficiencies – funds being generated on-reserve appear out of reach for Indigenous peoples.

It must also be said that this conversation happens against the backdrop of the much maligned point from Canadians that their taxes pay for the existence of First Nations. Clearly that is not true. But this continued misunderstanding and miseducation of mainstream Canadians has elevated this myth to the default counter-point for any discussion on Indigenous realities, including around gaming.

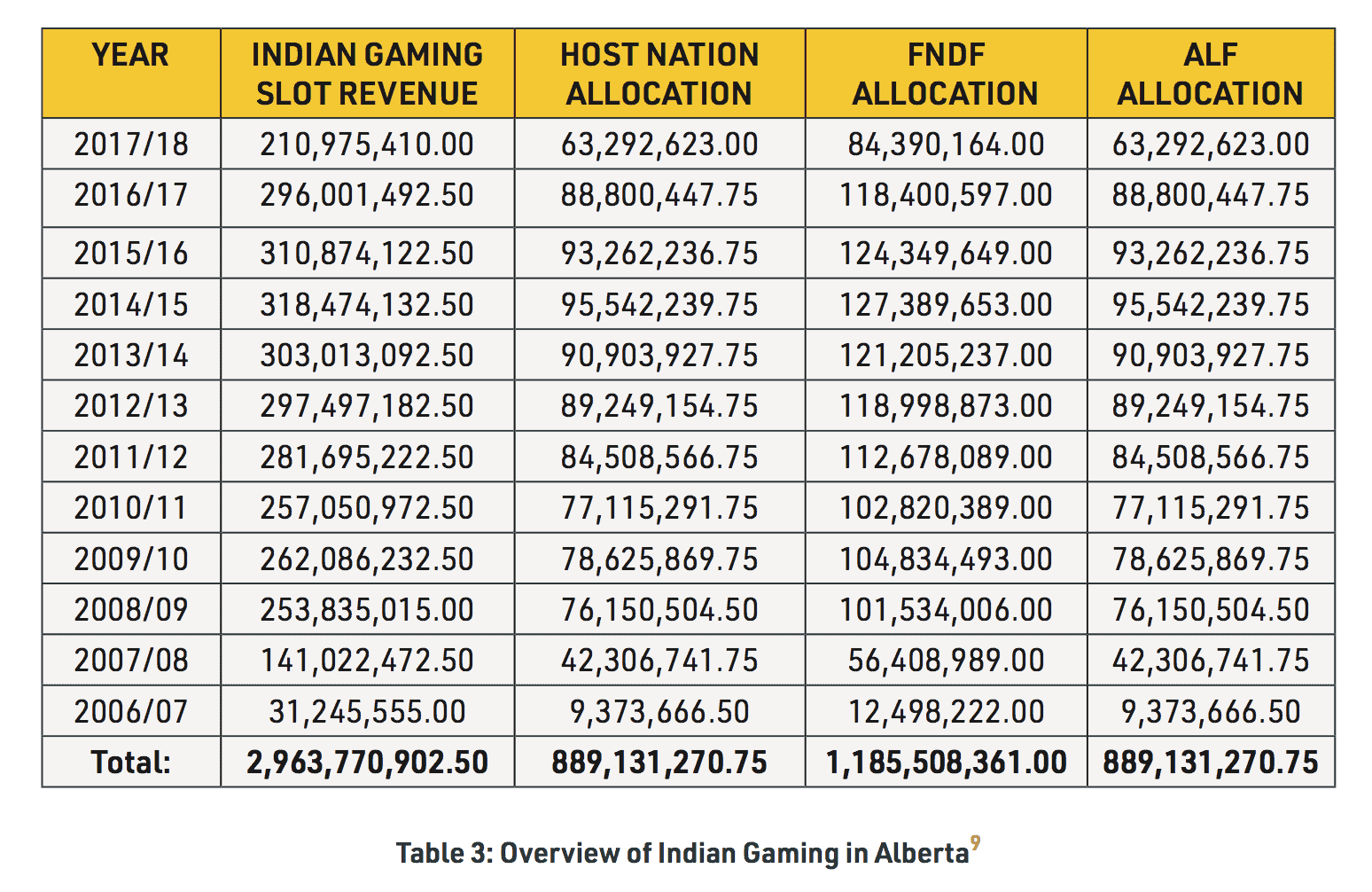

One final and global review of the data demonstrates the sheer quantity of funds that First Nations are actually raising to support Albertans. Below are the year over year allocations for the past ten years:

If we apply the same logic to the success of Indian Gaming in Alberta, one could easily argue that First Nations are supporting Albertans and the Alberta Lottery Fund by paying a Gaming Tax of 30%.

This First Nations Gaming Tax has contributed close to $900 million10 to the province directly since 2006, and at minimum $3 billion11 indirectly through the ALF.

The split of 30/40/30 remains enshrined in policy within Alberta with government and some First Nations unwilling to discuss. A large portion of this split appears out of reach to communities that would benefit the most from accessing it, with little hope for change on the horizon. Perhaps the time is right to re-examine this First Nations Gaming Tax, and have a meaningful dialogue regarding how Indian Monies are allocated, and how more can remain in First Nations communities.

Endnotes

1REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF ALBERTA | JULY 2013

2 Canadian Public Policy – Analyse de politiques, vol. xxxviii, no. 4 2012

3 Alberta Government, FNDF program guide 2018

4 http://albertalotteryfund.ca/aboutthealf/wherethemoneygoes.asp

5Canadian Public Policy – Analyse de politiques, vol. xxxviii, no. 4 2012

6Ibid.

7 https://ammsa.com/publications/alberta-sweetgrass/alberta-chiefs-reviewing-distribution-casino-revenue

8 Canadian Public Policy – Analyse de politiques, vol. xxxviii, no. 4 2012

9 Data collected and analyzed from: http://albertalotteryfund.ca/AlfWhoBenefitsApp/

10FN Contributions to ALF since 2006

11Overall Indian Gaming Revenues since 2006

Citation: Iamsees, Creezon. “The Current State of Indian Gaming in Alberta: Are First Nations Subsidizing the Province.” Yellowhead Institute, 22 May 2019, https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2019/05/22/current-state-of-indian-gaming-in-alberta/